The Smog of War

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

In Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 2013, a giant digital television was broadcasting pictures of a blue sky and white clouds: The toxic smog over the city prevented people from seeing the actual sky.

For years, some weather forecasters said the opaque skies were caused by “fog,” without alerting the public to the deadly cocktail of air pollution that had descended upon them. It’s a little like Chinese censors using the official phrase “political turmoil between the Spring and Summer of 1989” to describe a time that included the June 4 Tiananmen Square Massacre, when the government executed an untold number of unarmed pro-democracy protesters in the middle of the nation’s capital.

Political turmoil is plausibly benign. Massacre is decidedly not.

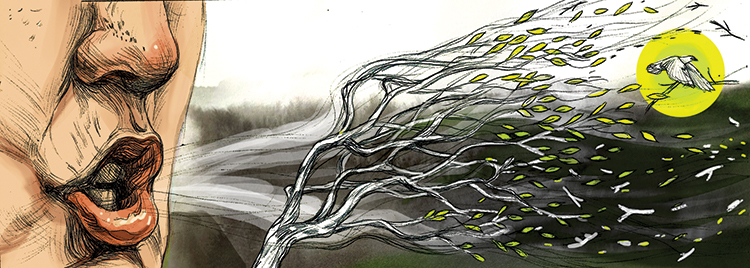

Smog, likewise, is not fog. According to the documentary “Under the Dome,” released in February 2015 by Chinese journalist and environmental activist Chai Jing, incidence of cancer in China is up 465 percent during the economic boom of the last 30 years. At one point, Chai urges that China must think of itself as at war with pollution. There are already casualties: According to Chinese health officials, 500,000 people are dying from poisoned air each year. Independent studies, including by the World Health Organization, put that number between 1 million and as many as 2.8 million.

In the U.S., the death toll is 200,000: We’ve exported some of our manufacturing and pollution to China, but not all of it.

Some of it is in Michigan’s Flint River, poisoning the people of Flint for the last several months despite ongoing complaints and concerns about the safety of the water. The city, long a center of heavy industry, can’t receive a federal disaster declaration to give it more aid because, according to federal and state authorities, what’s happening is, officially, a manmade catastrophe—disasters are from storms like Katrina. It is a distinction without a difference for the afflicted, most of whom are poor and black, some of whom will suffer a lifetime of health consequences from drinking their tap water.

Some of the pollution is in the City of Philadelphia. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation tells us that Philadelphia County has the worst air pollution in the state. The American Lung Association ranks the city the 11th most polluted in the nation. The number of Pennsylvanians who die prematurely each year from air pollution is approximately 5,000.

But it’s hard to call a slow and ongoing event an emergency, even if it is one. It’s easier to call it the status quo.

We should be calling it a public health crisis. One of the benefits of using those particular words would be that clean air advocates, including those who are opposed to further endangering our air by making Philadelphia a petrochemical hub, would gain a particularly powerful ally in the region: hospitals.

While many environmental organizations have tiny budgets and staffs—or operate on a volunteer basis—of the top 10 employers in the region, four are health care systems. Nearly one in four of our jobs are in the larger industry. Imagine if the veritable army of the health care sector was enlisted in the war against pollution?

Due to the Affordable Care Act, the question may not be if they join the fight, but when. The ACA requires hospitals to assess which illnesses are particular to the population they serve, and to invest in public health interventions that may prevent them. Here in Philadelphia, respiratory illnesses will be at or near the top of that list. Our asthma rates are twice the national average.

If Philadelphia’s health care systems prescribed clean air to our population and put their muscle behind it, our chances of filling the prescription are exponentially higher than if the traditional environmental community stands on its own. It would certainly be one way to win the war.

Great article. Unfortunately many organizations are paralyzed by the perception that taking on an issue like Philadelphia’s air pollution, or the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Refinery in particular, might hurt their brand. The environment is still seen as a political issue, and even hospital systems shy away from taking a stand I’m afraid. But articles like this are important in changing the conversation, and moving towards environmental protection, better health, and social justice for the people most affected by the profiteering of the fossil fuel economy. As a physician myself, I’m with you.

I’ve been thinking… with Darren Daulton being the most recent Phillie to succumb to brain cancer, and at least 4 Phillies who have been diagnosed with brain cancer representing a threefold increase over the baseline rate, why has the fact that Veteran’s Stadium sat directly downwind from the refinery not been mentioned? Or has it? Would love to see the Phillies, Eagles, and Flyers involved in this issue which pollutes and disgraces their surroundings.