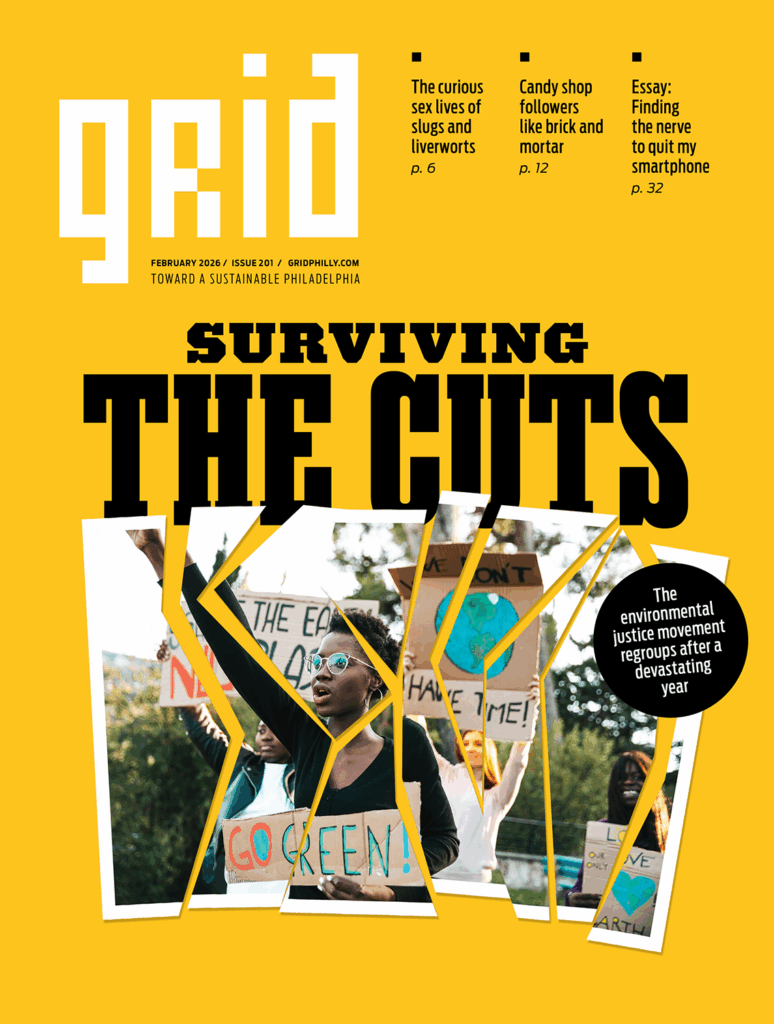

PhillyEarth permaculture students at the Village of Arts and Humanities stand with their teacher, Jon Hopkins (center) in the middle of their garden | photos by Jared Gruenwald

By Marilyn Anthony

The cob oven, hand-built from Warnock Street clay, was nearly finished when it suddenly collapsed. Jon Hopkins, Director of the PhillyEarth project thought, “Oh my god, this took us four days to build.” His crew of neighborhood kids saw his stricken look and said, “What are you worried about? We got this. We’ll be back tomorrow and we’re gonna build it again.”More than any competency test could measure, the kids in the PhillyEarth program showed in that moment how well they have mastered one of the key principles Hopkins wants to impart: resiliency.

PhillyEarth began in May 2012 as a program of the Village of Arts & Humanities. Other Village programs are arts-related and include dance, music, sculpture and garden design, all of which are intended to reclaim and enliven public spaces.

PhillyEarth uses the natural resources of the Village to teach youth between the ages of nine and 19 the principles of permaculture and appropriate technology: built solutions that areboth sustainable and suited to the site. Extending the 30-year mission of the Village by adding urban farming made perfect sense to Executive Director Aviva Kapust. “The history of the Village is rooted in transforming physical space with and for the community,” she says. “PhillyEarth is right in line with the type of work the Village wants to do. We try to be an incubator for risky ideas with a very logical premise.”

The Village is concentrated in an eight-square-block area near Germantown Avenue and North 11th Street, though its reach extends over approximately 260 blocks in a section of the city where 86 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. “The kids there really have nothing,” says Nick Renner, co-founder and director of engineering at Integrated Symbiotics. “PhillyEarth provides the opportunity to engage in old agricultural ideas and new technologies.”

Renner collaborated with Hopkins to build a solar-powered aquaponics system for PhillyEarth. It resides in an earthship made of reclaimed tires, bottles and scrap, sheltering aquaponics tanks in which fish and plants thrive.

The now fertile lots on Warnock Street contain a chicken coop, a pallet shed, raised beds of companion-planted vegetables and the resurrected cob oven, but the space was previously home to crack dens. Councilman Darrell Clarke accepted the Village’s petition to enroll the crack houses in his “40 Houses in 40 Days” initiative to tackle blight with the understanding that the Village would build a farm.

Hopkins began reinventing these lots by planting a willow fence instead of an energy-intensive, unwelcoming chain link fence. The willows form a graceful barrier protecting the farm naturally, and offer the first indication that this cared-for space embodies principles of permaculture.

Permaculture has multiple interpretations, but activist Guy Baldwin’s definition comes closest to PhillyEarth’s mission. “Permaculture is a holistic approach to landscape design and human culture,” he says. “It is an attempt to integrate several disciplines, including biology, ecology, geography, agriculture, architecture, appropriate technology, gardening and community-building.”

Rob Fleming, Program Director for Philadelphia University’s Masters of Science in Sustainable Design, recognizes the complexity of PhillyEarth’s undertaking. “Jon’s teaching the full practice of permaculture; teaching kids how to think in terms of cycles, of interconnected systems, of relationships between humans and the natural world. That’s why I think his is a very powerful model.”

Hopkins recruits youth for his outdoor classroom with a simple gambit. He asks them who they know who can do any of the things they’ll learn at PhillyEarth, like build a solar still or raise chickens. The answer is always the same: nobody. PhillyEarth builds cool skills and cool hands-on projects that give kids a powerful way to differentiate themselves. It’s also a lot of fun. “Jon is not only an incredible craftsman, designer and maker; the way he involves kids in every aspect of creating this farm is truly a work of art,” Renner observes.

Hands-on learning rules. Kapust emphasizes, “Jon does not do the work. It’s all done by the students. The nature of the work demands a level of excellence from them. We’re reaching kids who want that kind of engagement. They don’t do it for money or prizes. They do it for the pride of achievement.”

Hopkins recruited his first class of 10 students from the after-school program at the Village. Since then, over 300 youth have worked their way through the clever PhillyEarth merit badge system. Peer involvement fuels retention. Hopkins says, “When a kid sees another kid wearing a badge, he’s like “‘how’d he get that? I want that, too.’”

There are six beautifully designed badges: Up-Cycle, Water, Zero Waste, Smart Build, Grown and Energizer. Each is earned through completion of a specific curriculum. A motivated student could complete all six badges within one year. Youth who earn every badge are invited to become co-teachers at PhillyEarth, and are encouraged to become Neighborhood Sustainability Leaders by taking their skills into their church or school. PhillyEarth participants have, on average, been more boys than girls, but not by a significant amount. The program, which is open to everyone, is 100 percent free.

PhillyEarth imparts Science Technology Engineering Art and Math (STEAM)-based skills, and with funding from the American Honda Foundation, is crafting learning modules for use in public schools. Hopkins, a California native from the Bay Area, believes kids in underserved neighborhoods around the city and country are going to live their lives differently when the empowering experience of PhillyEarth helps them realize they’re not as empty-handed as they might feel. They have power to make changes and choices that are better.

Graduates of PhillyEarth will be consultants on a permaculture initiative for the Norris Square Neighborhood Project this fall. Kapust shares, “We’ve had tons of requests,” and the Village is “all in” when it comes to collaborating with other nonprofits and urban organizations. This is the real win, when PhillyEarth graduates can apply their knowledge to creating solutions for other sites.

The Food Trust, leaders of a $5 million grant program funded by GlaxoSmithKline, agrees. The Food Trust’s“Get HYPE Philly!” chose PhillyEarth to be one of a collective of 10 organizations with the goal of empowering 1,000 youth leaders to promote a culture of health in 100 middle and high schools. “Get HYPE Philly!” aspires to reach over 50,000 Philadelphia youth by 2017.

Hopkins thinks his program delivers the powerful trait of self-confidence and the self-assurance to take risks. “The reward [for students] is seeing accomplishments firsthand. What we started out with was nothing and, now we have something. And it’s like, whoa!”

Although not mentioned by name, Lauren Thain has been tremendously dedicated to the program and it’s children. She is the beautiful young woman on the left, looking very much like one of the students she works with. Lauren, a University of the Arts graduate and a sustainability advocate has been working with "the Village" neighbors and young people for several years now. "It’s been an amazing experience."