Story by Samantha Wittchen, Illustrations by Miguel CoThough it runs perfectly, Ric Temple’s Nissan Leaf can make him late. His electric-powered car rouses so much curiosity that Temple is regularly interrogated by passersby outside his South Philadelphia home. People take pictures of his car, as well as the charging station to which it’s attached. But Temple doesn’t mind—unless he’s in a hurry. He’s even taken the time to post an explanatory sign on the charging station to answer the frequently asked questions so, when he isn’t around, those who have their interest piqued can learn more.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Fairmount resident Brett Skolnick has had similar experiences with his Tesla S, the ultra-hip luxury electric car that Consumer Reports rated as the best car on the market.

“People stop me on the street and want to know more,” Skolnick says. “People have no idea that it was made in America. They think it’s an exotic car.”

In Wynnewood, Dave Park has felt the love for his Nissan Leaf as well. “Occasionally I’ll get someone who will look at me [in my car] and give me a thumbs up.”

If you’ve bought an electric car already, you occupy a space between eco-celebrity and side-show curiosity. But that is now starting to change. While electric car sales are still well under one percent of overall car sales, they’re starting to get a foothold in the market. According to the Electric Drive Transportation Association, a trade group based in Washington, D.C., sales for electric cars doubled from 2012 to 2013, right around 100,000 this year. Depending on your perspective, those numbers can seem both small and large, but consider this: In their first two years on the market, plug-in electric cars have almost doubled the sales achieved by hybrid cars in their first two years.

Evidence of the nascent market is appearing locally. Electric vehicle charging stations are quietly popping up throughout Philadelphia—on city sidewalks, in parking garages and at venerable institutions such as the Franklin Institute and Barnes Foundation.

The U.S. Department of Energy lists 36 public charging stations in Philadelphia, and that number is growing. And the range an electric car can travel on a single charge is expected to improve dramatically in the next few years. According to Forrest North, a former battery engineer at Tesla Motors and chief operating officer of Recargo, a California-based software and services company that supports the growth and adoption of plug-in car technology, battery energy density doubles every five years. It seems that finally, the electric car market is charging ahead.

All electric, or a gas backup?

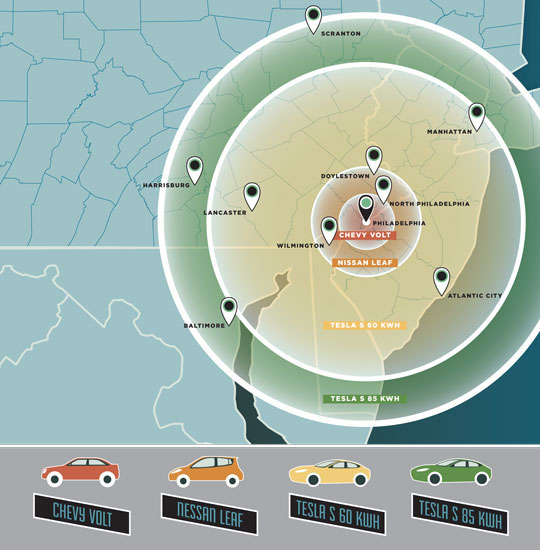

Plug-in electric vehicles reappeared on the market at the end of 2010 and fell into two categories — battery electric vehicles (BEVs), like the Nissan Leaf, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), like the Chevy Volt. BEVs do not have a back-up gas tank, meaning that once the battery’s charge has been depleted, your ride is over. Mid-range BEVs, such as the Leaf, can travel anywhere from 75 to 100 miles on a single charge, while long-range BEVs, such as the Tesla Model S P85, can travel up to 300 miles.

PHEVs, on the other hand, can continue to run once the battery’s charge is gone; a gasoline-powered generator provides electricity for the electric motor that propels the car. PHEVs generally have shorter battery ranges—the Volt is limited to 38 miles per charge—but can travel another 300-plus gas-fueled miles on top of that.

Fundamentally, BEVs and PHEVs are different from hybrid vehicles in that they operate completely on an electric motor, whereas hybrids use an electric motor in conjunction with a gasoline engine to power the car.

PlugShare by Recargo – This charging station monitoring app keeps you from desperately searching for a charging station with a map to the nearest one right at your fingertips, showing public and private stations, including many that are free to use.

Where to charge

Early adopters bought more than 17,000 electric vehicles in 2011, but the lack of charging infrastructure made it challenging to charge vehicles outside of the home. The first public charging station in Philadelphia was installed at the Liberty Gas Station on Columbus Boulevard in November 2010, but by early 2011, only 1,972 charging stations existed across the U.S., and most of those were concentrated in California. According to the Department of Energy, that number has ballooned to 19,472, with a growing number located in the Northeast Corridor.

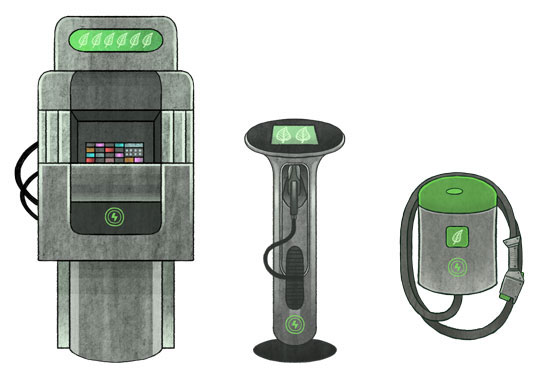

Charging stations may be on the rise, but there is a significant difference in power supplied. Level 1 charging uses the common 120-volt wall receptacle, and is the slowest. A Chevy Volt needs 10 to 16 hours to fully charge at this level. Step up to Level 2 charging, which uses a 240-volt receptacle required for a household clothes dryer, and the Volt’s charging time is cut down to four hours. Level 2 chargers are the most prevalent at public charging stations, adding approximately 10 to 20 miles of range for every hour charged. Direct current fast charging, also called Level 3 charging, can fully charge a typical electric car in a half hour. Unfortunately, only 368 Level 3 charging stations are currently in use today, according to Recargo.

Still, the lack of Level 3 public charging stations does not seem to present a meaningful barrier to today’s electric car owners, the majority of whom—81 percent—charge at home, according to a 2013 study release by PlugInsights, Recargo’s research arm.

From L to R, the three levels of electric vehicle charging stations: Level 3: 1/2 hour average time needed for full charge; Level 2: 4 hours average time needed for full charge; Level 1: 10-16 hours average time needed for full charge.

Parking perks

While many of these home-chargers live somewhere with easy access to a driveway or a garage, that doesn’t really help those living in a densely packed and less car-friendly city. And that’s why, in 2007, Philadelphia City Council passed legislation allowing electric vehicle owners to apply for a designated electric vehicle parking space in front of their homes.

Temple, who lives two blocks from Pat’s and Geno’s in South Philadelphia, charges his Nissan Leaf in front of his house using his Level 2 charging station. The dedicated parking space was a major motivator for Temple, whose elderly grandfather lives with him.

Temple’s two adjacent neighbors had to sign off on the space, and Temple added the charging station in conjunction with lighting and sidewalk improvements. It took a month and a half to get approval and the charging unit itself was free through the Department of Energy-sponsored EV Project, which aims to deploy electric vehicle charging infrastructure in nine states and the District of Columbia. Although Temple used public charging prior to securing his parking space, he primarily charges at home now, bypassing the expense of parking in a garage that offers a charging station.

Skolnick was also motivated by the chance for free parking for his Tesla Model S. In April 2013, Skolnick was just the fourth person to apply for electric vehicle parking in Philadelphia, and he has enjoyed the flexibility the space provides. “One of the realizations we’ve had is that we can get in the car at 8 p.m. and go out and come home and have a parking space,” Skolnick says.

How far one can drive on a charge depends greatly on the make and model. Here are some examples of four electric cars and an estimate on how far out from the heart of Philadelphia one could get–and still return home.

Range anxiety

One reason Skolnick opted for the Tesla was its superior range—he drives 105 miles round trip to Princeton for work each day. Temple’s biggest concern when downsizing from a Cadillac Escalade to the Leaf was the fear that the car’s battery would run out of juice and leave him stranded. Fortunately, that hasn’t happened.

“I’ve gone to Atlantic City from Philly,” Temple says. “It was the most nail-biting trip I’ve ever taken, but I made it.”

Known as “range anxiety,” such concerns are common among electric car drivers. But future technological improvements and expanding charging infrastructure could eliminate that concern altogether.

“It’s a two-headed issue,” says Norman Hajjar, managing director of PlugInsights. “On one hand, if there are breakthroughs in technology and mid-range BEVs ended up with a longer range, we’ll be all set. It’s a pretty safe bet that’s not going to happen anytime soon. So barring that, the next best thing to do is to build out the infrastructure so that [drivers] can rely on the fact that there’s a vast recharging station network so they won’t get stranded.”

Hajjar believes the best way to do that would be for the government to make a Manhattan Project-esque push toward increasing the number of Level 3 chargers. This would drastically reduce the time it takes to “refuel” an electric car, bringing it closer to the amount of time it takes to stop at a gas station. The main barrier to Level 3 charging right now is the steep cost, but more companies are starting to see a market opportunity, based on research from such organizations as PlugInsights.

In Hajjar’s opinion, we won’t reach a tipping point for electric cars until we build out the infrastructure sufficiently to eliminate range limitations. Currently, most electric car owners must rely on another gas-fueled car for longer trips, or they need to plan carefully. For example, Nissan dealerships all offer free Level 2 charging—during business hours only—and according to Steven Dodson, a customer representative on Nissan USA Chat, “The charging stations are intended for universal use.” But they also advise calling ahead of time to schedule a charge. All of this makes longer trips potentially more complicated, and this can discourage anyone who can’t afford a second vehicle.

“Until we get to the point where the vehicle can be the only vehicle for an individual, we won’t get huge market penetration,” he says.

Yet over the past few years, improvements in battery technology and charging infrastructure, coupled with falling prices (both General Motors and Nissan have reduced their prices by at least $5,000 from the first models) and a generous federal tax credit of up to $7,500, have fueled an increased demand for both PHEVs and BEVs.

How clean is it?

Due to public policies that have been implemented to encourage the growth of the electric car market, it isn’t surprising that some have expressed skepticism about their viability. A major anti-EV claim has been that electric cars operating in fossil-fuel heavy states such as Michigan, which draws 72 percent of its power from coal-fired power plants, actually produce more emissions than gasoline-powered vehicles. While numerous peer-reviewed articles have reached the conclusion that, from cradle to grave, electric cars are the cleanest option, the Union of Concerned Scientists’ comprehensive report, “State of Charge,” does the best job of refuting this anti-EV claim.

After examining the emissions of regional electrical grids throughout the U.S., which vary widely by fuel source, the report found that, even in regions that produce the most emissions from electricity generation, electric vehicles have lower global warming emissions than the average gasoline-powered vehicle on the market today. The Philadelphia region earned a “Best” rating in the report, meaning that electric vehicles charged from our regional electric grid achieve more than a 46 percent reduction in global warming emissions when compared with a 27 mpg vehicle. Drivers who want to maximize their positive environmental impact can pair an electric vehicle with solar-powered charging to reach zero direct emissions. Even without solar charging, electric vehicles in Philadelphia produce global warming emissions equivalent to a 64 mpg gasoline vehicle, according to the report.

The good news is that these figures are only going to get better for electric vehicles. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have adopted renewable energy standards—Pennsylvania’s is 8 percent by 2020—so the electricity grid will continue to get cleaner. And while fuel standards for gasoline-powered vehicles continue to improve as well, it’s unlikely that any car operating solely on an internal combustion engine is going to hit the 64 mpg mark anytime soon.

Another criticism of electric cars is that battery production is extremely energy intensive, and the process of mining raw materials for battery production is harmful to the environment. While it’s true that producing an electric vehicle using today’s methods requires more resources than producing a conventional vehicle, mainly due to the large batteries, it’s unlikely that this will always be the case. Today’s existing gas-powered automotive industry has benefitted from decades of research and manufacturing process refinement, and electric vehicles could easily benefit from the same.

Yet even taking higher emissions from manufacturing into account, over the life of the car, an electric vehicle is still the cleanest option on the road. In a survey of six peer-reviewed academic studies, the National Resources Defense Council found that in every case, electric vehicles boasted lower emissions, ranging from 28 to 53 percent less than conventional vehicles. Additionally, batteries are most likely reused or recycled. A spent battery, defined as one that only retains 70 percent of its original capacity, can be repurposed to provide grid energy storage, and conventional lead acid car batteries are recycled at a rate of 96 percent, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s data from 2011.

While the scientific community has overwhelmingly confirmed that electric cars are already the most environmentally sound option on the market, perhaps the most compelling argument in support of the future of electric vehicles is the fact that they will continue to improve while gasoline vehicles may have been optimized as much as possible.

“At some point, your electric car will be just as cheap and usable as a gas car, but it’s going to improve from there,” says Forrest North, Recargo’s chief operating officer. “Gas cars aren’t going to improve.”

The Big Picture

Dave Park says that his motivation for buying an electric car was largely environmental. “What better way to make my actions match my intentions?” Park says. He had a charging stat

ion installed in his detached garage (also through the EV Project), and although he mostly charges at home, he occasionally charges at a public station located at a Walgreens near where he volunteers in Northeast Philadelphia. Most days he only drives the 38 miles round trip between work and his home, but on days when he volunteers, he drives up to 75 miles. On those days, he monitors his driving habits carefully to make sure he can make it the full distance.

Temple echoes Park’s sentiment about driving habits: “You change the way you drive when you drive one of these cars.” He says he’s much more relaxed and respects cyclists more now that he drives a Leaf. “I don’t know if it’s the increased environmental awareness or what,” he adds.

Temple has seen dramatic financial results as well. He had previously driven a Cadillac Escalade, and filled its 30 gallon tank three times a week. He estimates his annual gas savings are a shocking $20,000, a figure that pays for the Leaf and charging station in well under two years.

Skolnick adds that driving an electric car requires that you plan long trips based on the location of charging stations. He doesn’t think it’s a bad thing—just different. Temple, however, is looking forward to the installation of more rapid charging stations on the I-95 corridor between New York and D.C.

Driving enthusiasts

As for the performance of electric vehicles, all three owners are in complete agreement—it’s awesome.

“When people drive the car and feel how powerful it is, they say, ‘Oh wow! This isn’t what I expected an electric car to be,’ ” Park says. “What makes the Leaf feel like it’s a luxury Cadillac is that it’s so smooth—it’s a luxurious experience driving an electric car.”

The unbridled enthusiasm of electric car owners is infectious, much like it was for hybrid owners a decade ago. If we’re not at a tipping point yet, we likely will be soon as prices continue to drop, charging infrastructure improves and technology continues to advance. In fact, technology is developing so rapidly that the biggest concern for potential electric vehicle owners may be owning an outdated car. Temple’s advice for drivers considering making the switch to an electric car? “Don’t buy one—lease one.” Otherwise, it’s full speed ahead for electric vehicles.

Well, the thing that jumps out at me the most about this article is the beginning. It intrigues me about the way Samantha Wittchen writes about the ways she thinks people are looking at her and her car.

its amazing nice article i m not able to drive car but i want to drive car