story by Lee StabertThis interview was conceived as a back-and-forth, but give an Italian intellectual open-ended questions and you’ll get expansive—and fascinating—open-ended answers.

story by Lee StabertThis interview was conceived as a back-and-forth, but give an Italian intellectual open-ended questions and you’ll get expansive—and fascinating—open-ended answers.

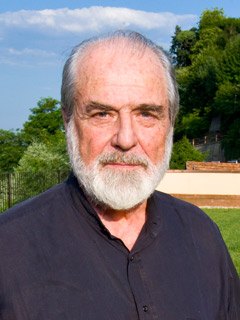

A retrospective of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s thoughtful, dynamic work (From One to Many: 1956-1974) opened in November at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Recently, Grid had the opportunity to meander through the galleries before sitting down at one of Pistoletto’s grand “Mirror Tables” for a chat with the artist. These huge, stunning tables are cut into the shapes of the world’s seas—Mediterranean, Caribbean—and offer a literal representation of global community.

Bringing together disparate people and cultures through art and engagement is a central mission of Pistoletto’s work. It is also the thrust behind Cittadellarte, his interdisciplinary collective in Biella, Italy, working on issues as diverse as fashion, architecture, politics and ecology.

There is a direct line between Pistoletto’s current socio-political work and the sly, interactive mirror paintings that form the core of his retrospective. Standing in front of the painted, polished stainless steel, the viewer becomes part of the work. It’s yet another tangible interpretation of the power of art.

How do you think art functions as a community-builder? And how could it function better?

Michelangelo Pistoletto: Personally, I started from visual art, and from visual art to, let’s say, touchable art [laughs], to virtuality, to reality. With the vision of the mirror—where the viewer is included—I thought that the viewer was society. And the present time that is reflected in the world—in the mirrors—is existing reality.

Also, we must put them together: art and different sectors of public life. So, I started to think about how art could be useful for socially-responsible transformation. That’s not easy—to create the connection that makes understandable the possibility of art. I thought that it was not easy, but necessary.

That’s why I created the Cittadellarte, a place where we live together and work together. But it’s not a traditional idea of community. It’s a place where we live in the day, but we live not only practically, but with ideas. It’s a way to be able to interfere with the social life. So, we created different offices. Each one has the name of a sector: economy, politics, communication, spirituality, work, production, architecture, fashion and food.

How does “sustainability” connect back to these projects?

Sustainability is a word that is used, and abused. We have to think that even if it is abused, it is something important as a basic concept. What we do, in order to protect and save the world in which we live—this is the meaning of sustainability. To leave a sustainable world to the future. And this is a big job. Of course, it’s not possible to change everything in one minute, but the process has to be ongoing. If we don’t believe in the possibility of working towards that direction, we will not succeed.

For example, we try to work with architects to propose projects that will produce energy and preserve energy. We also think about houses that can connect the people—to have a closer rapport—and introduce a way of living that is much more connected.

That connection is something that art can make. It can transform the typical desire—that is driven by the ultra-consumer system—to another kind of desire. In Italian, we say condividere. [Asks interpreter for definition.] Sharing! Sharing space, sharing time, sharing economy. Sharing is an important issue in order to change the isolation that relegates people to only rapport with product.

We want to work with a new concept of design, and this is especially what I think art can do—to bring pleasure from something that is not just buying. But for that, also, you have to think about new concepts of production. I can be producer and consumer at the same time. I produce something for you, and you produce something for me—and the economy becomes more closed. And we can also have better quality of products.

We are working with many things. For example, fashion is very important to us—to use only textiles that are produced with sustainable materials, made in a sustainable way. We must be involved in not only an aesthetical, but an ethical way.

Walking through the exhibit leaves a strong impression. A common thread is engagement and interaction—even collaboration—between the viewer and the work. To come in here and sit around these tables is very fluid; it makes a lot of sense. Will you talk a little about the mirror tables?

With the mirror tables, you don’t just look into the work; you sit around the table and meet the other people. People who are represented by the geographical design of the tables. Here, we are around the Caribbean—with all the problems that unite and divide the north and south of the American continent.