essay and illustration by Jacob Lambert

essay and illustration by Jacob Lambert

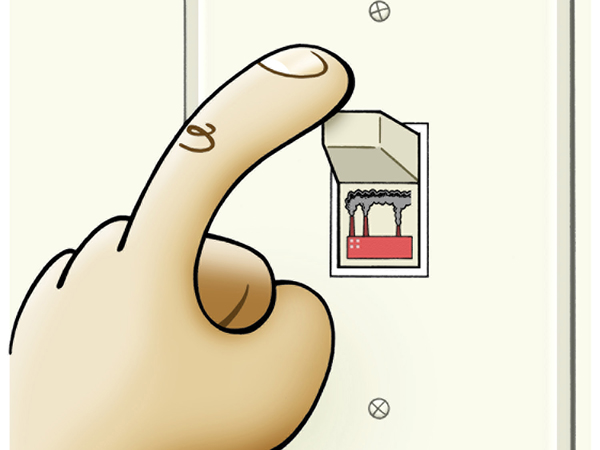

Environmentally speaking, there are a few things i’d like to experience before I die. Hopefully, the coming decades will bring a collective snubbing of our oil-centric exurban lifestyle. A move towards energy creation that doesn’t involve strip mines and cluster bombs would be also encouraging, as would genuine mainstream interest in nature, an end to industrial farming, sincere corporate stewardship and a cap on CO2 emissions. For any or all of those changes to occur in the near future would be wonderful. But, in the end, I’ll expire with a smile if just one thing comes to pass: My wife turns off the lights when she leaves a room.

Kirsten’s childhood home abutted a small, dense forest, and when the sun went down, the lights came on. The prospect of a dimly-lit house so close to those woods—teeming with imagined horror-movie maniacs—rightfully freaked her out. Leaving the lights on was a way to calm the nerves, an easy source of comfort. Over the course of her first 18 years, that habit steadily ingrained itself, and now, though we live miles from anything resembling a forest, the practice continues. Kirsten and I have been together for 12 years, and for 12 years I’ve been re-entering rooms she’s just left, flipping the switch.

Her habit isn’t particularly horrible. It’s not like she’s sacrificing goats or reading Ann Coulter. As pet peeves go, it’s in that odd middle ground: just enough to annoy me, yet just minor enough to make me feel like a scold when I, um, scold her about it.

Sometimes, I’ll attempt the “electricity bill” argument, which generally gets me nowhere. A more successful approach invokes personal responsibility: Our burning bedroom light, I explain earnestly (and not at all pedantically, I promise), is being powered by something, somewhere—maybe coal, maybe wind, maybe water. Yes, I’ll say, it’s just one bulb, powered perhaps by a single nugget of coal. No, shutting off that light won’t alter our course, won’t cool down the globe. But, I’ll continue, that’s not really the point—we each must do what’s within our own individual reach.

Stirring stuff, I know.

In other matters of conservation, Kirsten is quite conscientious—so when she pledges to try and shut off the lights, she really does mean it. But ultimately, no amount of speechifying seems likely to break her habit. Those creepy childhood woods will always be swaying in the far reaches of her mind. And that breed of fixed thinking represents the real problem—not just for my wife and our overworked bulbs, but for all of us. Because when it comes to preservation, we ultimately do what’s comfortable—and when change is needed, we may be willing but not actually able. Whether it’s turning out the lights, ditching our cars or swearing off meat, in the end many of us aren’t as capable of change as we’d like to think. Multiply our personal indulgences by 300 million, and you begin to see the contours of a crisis.

A partial solution, for each of us, is simply to try harder. As for me, I’ll try to quit using the Dustbuster to pick things up off the kitchen floor when a dustpan will do. It’s a flagrant waste of electricity—and I’m pretty sure it drives Kirsten crazy.