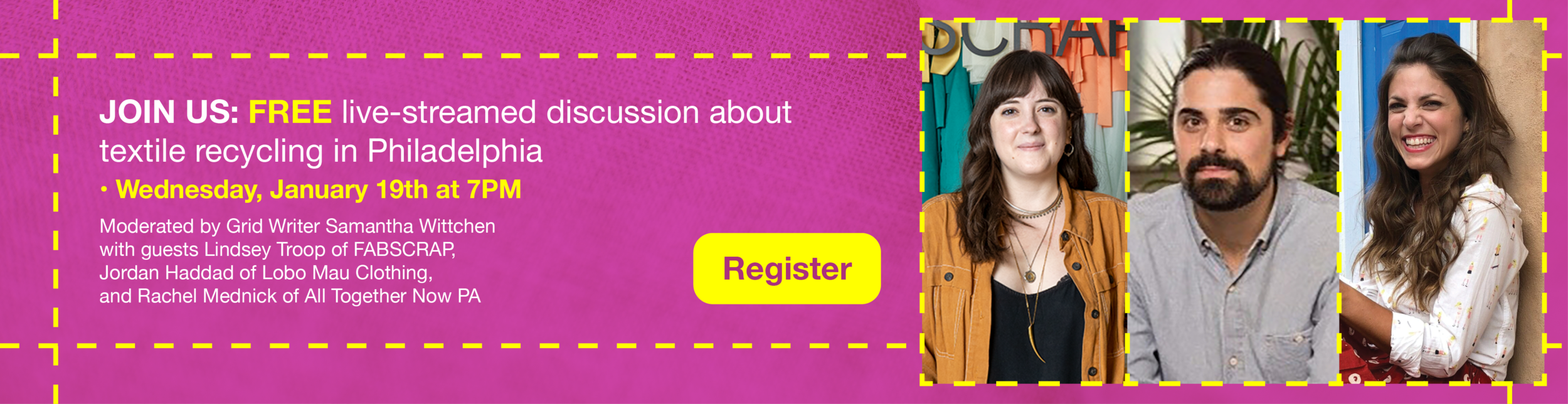

Lindsey Troop is the regional manager for Fabscrap Philadelphia. Photography by Drew Dennis.

Fashion Forward

By Samantha Wittchen

Jordan Haddad sat in his 1,800 square-foot studio in South Philly’s BOK. The waste was piling up.

His local sustainable fashion company, Lobo Mau, had been saving fabric scraps from all of the clothing it designed and produced, but by summer 2021 the storage bins were at capacity.

“We ask the manufacturers to save scraps from producing our clothes for us, and we use them to make one-off pieces,” Haddad says of his zero-waste, slow fashion company.

Lobo Mau is an outlier in the world of fashion. Design houses typically overbuy textiles to create the next season’s styles and then trash yards of unused fabric when the process is over. More waste is then produced in the production process. The same issues repeat themselves in the home goods industry, and the net result is an enormous textile waste problem.

“As we learned about the waste problem in the fashion industry, we wanted to better ourselves each year and focus on sustainability,” Haddad explains.

But while Lobo Mau is breaking this cycle within its own business, another player new to Philadelphia is aiming to solve this problem on a larger scale.

Fabscrap, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit, collects pre-consumer textile waste that hasn’t yet been turned into garments or other finished goods from businesses and individuals. It then sorts the textiles for reuse and downcycles the rest. At its first operation in New York, the organization picks up roughly 6,000 pounds of textiles a week from a host of brands, including Philly-based Urban Outfitters.

“It’s like the universe said, ‘Okay, we have everyone we need here. Let’s make it happen in Philly.’”

— Eleanor Turner, founder of The Big Favorite

Urban had been working with Fabscrap for almost three years when talks began to expand Fabscrap’s role from just a recycling partner to helping Urban generate change in the industry beyond its own operations.

“They wanted to expand their sustainability efforts,” says Lindsey Troop, regional manager for Fabscrap Philadelphia. Urban offered them a working capital grant to help them open a Philly location and to provide operating funds for their first two years, and Fabscrap accepted.

Fabscrap arrives in Philly at an auspicious time.

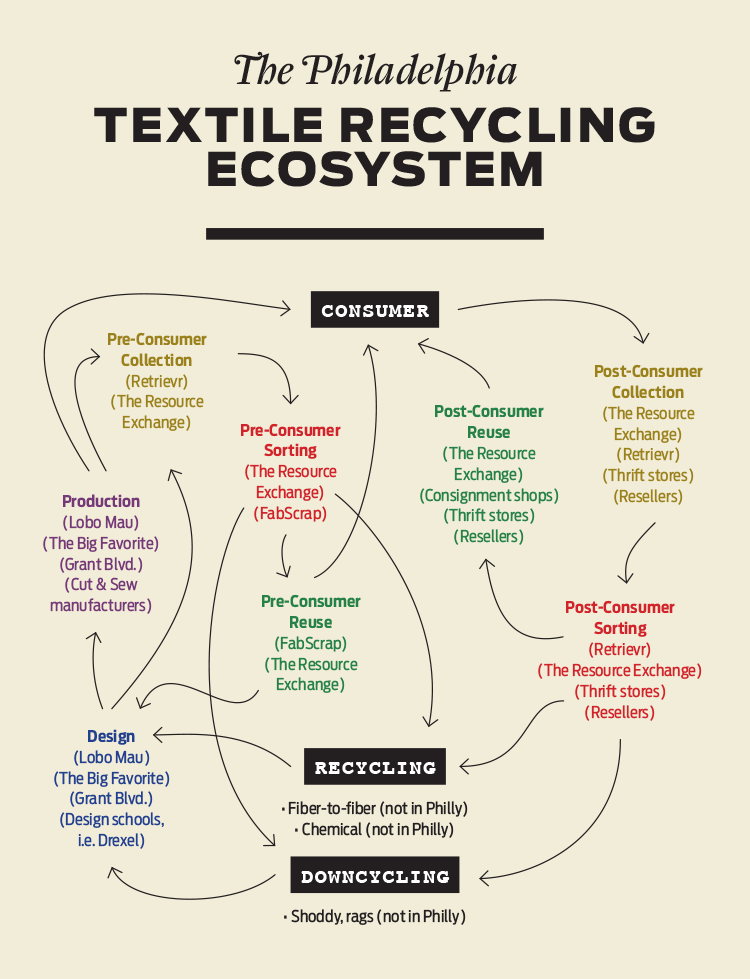

Philadelphia’s textile recycling movement has been brewing in fits and starts for years. Now the movement seems poised to shift the local textile system to a circular one that designs out waste, keeps textiles in use for longer periods and recycles end-of-life materials into new ones.

As director of programs and operations at Circular Philadelphia, a non-profit focused on advancing the circular economy in the region, I see this shift happen first hand, and it’s exciting. Even a year ago, there was no collective effort to advance textile recycling in the region. Now I see brands, reuse organizations and recycling logistics companies coming together to tackle this problem in a coordinated way to accelerate this work.

Eleanor Turner, founder of zero-waste clothing basics brand The Big Favorite, agrees.

“The interest in textile recycling right now in Philly is incredible,” says Turner, whose company designs its products, primarily T-shirts and underwear, for circularity and takes back garments for recycling at the end of their life. “It’s like the universe said, ‘Okay, we have everyone we need here. Let’s make it happen in Philly.’”

Volunteers who sort get the perk of free fabric from Fabscrap, five pounds for each three-hour sorting session.

Fabscrap officially opened the doors to its Philadelphia location in BOK, in the former vocational school’s cafeteria, on November 15, America Recycles Day.

In the light-filled, 6,800-square-foot space, volunteers and staff alike sort textiles. Staff also operate a fabric resale store that’s open to the public by appointment. By the end of November, 86 volunteers had already helped sort through about 5,300 pounds of pre-consumer textiles, and 153 shoppers had bought almost 1,000 pounds of reclaimed fabric at its “fabric thrift shop.”

Fabrics range in cost based on how quality, but the shop has fabrics at all price points—cheaper than what you’d pay retail. There is even a “pay-what-you-wish” bin.

Volunteers who sort get the perk of free fabric from Fabscrap, five pounds for each three-hour sorting session. It’s a great way for students and new designers on a budget to get high-quality fabric at low- or no-cost.

Kimberly McGlonn, founder and CEO of zero-waste fashion brand Grant Blvd and Fabscrap’s inaugural featured Philly designer, believes that this expanded access to reclaimed fabrics removes a roadblock for local designers and brands with a desire to become more sustainable.

Volunteers and staff at Fabscrap help sort collected textiles based on their fiber composition.

“I think one barrier has been ease of access, and having Fabscrap here makes it easier for home sewists and brands to think about their supply chains in more climate positive ways,” says McGlonn.

Fabscrap’s sorting process works like this. Bags filled with textiles from customers—the organization accepts donations from both corporations or individuals—arrive at its facility, which Troop then weighs and labels with each brand’s unique identification number. Volunteers then sort the contents of individual bags at one of 16 sorting stations. Textiles made solely of wool, cotton or polyester are separated, and anything with spandex in it is set aside. Any materials in good condition that measure a half-yard or more are sold in the thrift shop area.

Once a bag is sorted, Fabscrap weighs each category of material and logs the data. Since 2016, Fabscrap has worked with 550 fashion, interior design and entertainment brands to collect their unwanted textiles and provide data back to the brands about what types of waste they’ve generated and what happened to it.

Troop says that in an industry that’s notoriously opaque about production and waste practices, Fabscrap is transparent.

“We’re letting the industry know what we have and exactly what we’re doing with it,” says Troop. “We put transparency and the data front and center.”

The conventional lack of transparency has held back true textile recycling for a long time. It is often difficult for people in the industry—let alone consumers—to determine what actually happens to textiles that have reached the end of their life and can’t be reused.

It’s something Karyn Gerred, executive director of The Resource Exchange, a Kensington creative reuse center that accepts non-clothing textiles, describes as a shipping container-sized problem. There’s a portion of the textiles her organization receives in donations that can’t be resold because they’re too low quality or made of fibers that people just don’t want (mostly polyester or polyester blend).

Since she can’t follow these undesirable textiles through the chain of custody after they leave her facility, she cannot be sure they’re not dumped somewhere in the Global South (as was revealed in November to be happening in the Atacama Desert in Chile). She’s been storing them in a shipping container until there’s a solution she can trust. It’s less than ideal, and she’s running out of space with no good solution on the horizon.

Currently, Fabscrap sends anything that can’t be reused to a textile downcycler that shreds the textiles into a product known as shoddy, a fluffy pile of fibers used for insulation and mattress stuffing.

The downcycler can accept any fiber content, except spandex. Fabscrap would prefer to send these textiles to a recycling facility that could turn them back into fibers suitable for weaving into new fabrics, but there are only a handful of these fiber-to-fiber recycling facilities scattered across the country, and Troop says they can’t handle Fabscrap’s volume.

While Fabscrap continues to sort and keep data on the single fiber content textiles it receives in the hopes of one day sending them somewhere they can be turned back into new textiles, that still leaves the problem of everything else—the mixed-fiber textiles that can’t be turned back into new textiles and continue to grow in market share because they’re often cheaper for brands to produce.

“The difficulty is with mixed-fiber textiles, like polyester and spandex and all of those things that are made with fossil fuels,” explains The Resource Exchange’s Gerred. “The nature of these materials prevents them from being recycled into useful materials. They are downcycled.”

And while Fabscrap cofounder Camille Tagle says she’s confident Fabscrap’s shredder actually creates insulation from its mixed-fiber waste because they’ve provided samples of the insulation they make for use in Fabscrap’s educational programs, many shredding facilities are relatively opaque about their operations.

That lack of transparency has been a major motivator for Kabira Stokes, CEO of Retrievr, a residential clothing and home textile collection company (which also collects electronics) contracted by Fabscrap to collect textile waste from businesses.

Stokes came from a decade in the e-waste industry, where she says there are laws in place that allow end-of-life tracking to make the chain of custody of a product’s disposition transparent.

“There is none of that in textile recycling. The moment it leaves our warehouse, we lose any sense of transparency because there is no system for that tracking,” laments Stokes.

Shocked by this lack of transparency, Stokes decided to bring more of the disposition process in-house.

She identified that sorting was the first step to gaining control, and having an industrial-scale, post-consumer, textile-waste sorting facility in the region would fill in a gap in getting to textile circularity.

In November, Retrievr conducted a sorting pilot with the help of Columbia University Business School students who developed a portable, hand-held device using spectrometer technology to identify the component fibers of textiles.

The sort revealed that Retrievr could recycle 60% of the non-rewearable garments and other textiles it collects through existing fiber-to-fiber recycling technology. The rest must be downcycled.

Stokes plans to scale up Retrievr’s sorting capabilities, but to get to full circularity, she believes the region needs a textile recycling or shredding facility. Currently, the closest shredder is the one that Fabscrap partners with on Long Island. The next closest is in North Carolina.

Stokes has considered adding a shredder to Retrievr’s operations, but so far she can’t find a way to make it economically feasible. Shredding is a low-margin business, and according to Stokes, the market is currently saturated with an oversupply of shoddy.

That’s where the Textile Recycling Task Force comes in.

Led by Rachel Mednick of All Together Now PA and composed of representatives from Fabscrap, Retrievr, The Resource Exchange, The Big Favorite, Circular Philadelphia and Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability, it’s a who’s who of players in the textile circularity space.

Together they are spearheading the collection of better data on what currently happens to unwanted textiles in Philly with the goal of attracting a textile recycling facility to the region.

The City of Philadelphia’s 2017 Residential Waste Composition Study—its most recent—showed that residents discarded 31,577 tons of textiles, or slightly more than 5% of Philly’s residential waste, that year.

That’s 40 pounds of textiles per Philadelphian.

The number doesn’t account for pre-consumer textile waste produced commercially by designers or manufacturers, and it doesn’t include figures for pre- and post-consumer waste that’s donated to reuse organizations or thrift stores.

To get better data, the task force launched a survey for residents in and around Philly to provide information on how much clothing and other textiles they dispose of each year as well as how they dispose of it. They will similarly be surveying designers and reuse/resale organizations to collect information about the waste they generate.

“The data collection piece is huge,” says Mednick. “We know we have a problem, but we don’t know exactly how big that problem is.”

After quantifying the scale of the issue, she adds, it’s about building the infrastructure to rehome, reuse and then recycle.

While a recycling facility fills a critical circular infrastructure gap, Mednick cautions that we need better reuse systems in place too, to rehome textiles on a large scale. Organizations like Fabscrap and The Resource Exchange help fill this role, but Mednick is quick to point out that we still have huge gaps in dealing with post-consumer waste.

A Fabscrap sorter holds a fabric sample.

Turner also sees gaps in expertise when it comes to turning recycled fibers back into fabrics locally. “Combing, carding, respinning–we need the people who hold the knowledge to help set this up,” she says. She also argues that we need more investment.

Stokes agrees.

“We don’t understand the economics of this yet,” says Stokes. “Who is ultimately going to pay for this? What is the sustainable business model here?”

Still, Mednick is optimistic that Philly is at a point where it can fill these gaps.

“We have organizations coming in that make the logistics of textile recycling more feasible. It shows that Philly is finally taking textile recycling seriously,” she says.

Indeed, Retrievr’s plan to sort post-consumer textiles in the Philadelphia area plugs one of those gaps in the system. Brands like The Big Favorite and Grant Blvd fill another role. In addition to operating a take-back program for their garments, The Big Favorite is working with other brands to help them design garments for circularity. Ultimately, they’ll even help those brands with the actual recycling.

“It looks like a lot of conversations right now,” says Turner. “But we will start aggregating cotton garments here in Philly to make sure they’re baled to go to mechanical fiber-to-fiber recycling facilities.”

Grant Blvd sources reclaimed fabrics from within 25 miles of Philadelphia for all of the garments it designs and produces. This allows the business to bypass the global textile supply chain and its massive contributions to climate change.

“Global supply chains are really anti what’s good for the planet,” says McGlonn.

She adds that Grant Blvd’s hyperlocal operations also allows the business to use fashion as a vehicle for educating consumers on the unethical nature of the global supply chain.

“We often overlook lands that have been colonized and the burden that has been placed on them to maintain these supply chains,” McGlonn says. “I’m interested in making sure we’re centering sustainability conversations around conversations about ethics.”

Another key piece of getting to textile circularity is enacting policies that support circular practices, something that Circular Philadelphia is well-positioned to advocate for.

Both Stokes and Turner think that extended producer responsibility (EPR) and disclosure laws that require brands to take responsibility for the textiles they’re putting into the world are important for advancing a circular textile system.

Statewide, there are opportunities to ban textiles from landfills, like Massachusetts will do beginning in November 2022.

The last piece of the puzzle–and possibly the most confounding one–is how to change the habits of individuals, designers and brands to curb consumption and overproduction.

Gerred believes that consumers need to better understand how the downcycling process actually works. She says that for too long the message from clothing donation organizations and major brands that offer textile “recycling” led consumers to believe incorrectly that once they drop off their unwanted textiles, they truly are reused or recycled.

The problem is that’s not true. While high-quality clothing donated to thrift organizations typically finds a new home domestically, low-quality fast fashion and clothing with stains or holes in it is downcycled for rags or shoddy or shipped overseas to become a developing country’s waste problem.

“As long as the perception exists that when you recycle your sweater, it gets turned into a new sweater, we can’t solve this problem,” argues Gerred.

Mednick concurs.

“Really the problem is overconsumption, and until we solve that problem, we can’t solve the overarching waste problem,” she says.

As does McGlonn.

“We need to find a way to medicate the consumptive addiction of society,” argues the Grant Blvd founder. “We need to resist this idea that we should get what we want immediately when we want it. If we don’t make that shift, then I feel less optimistic about us as a collective to slow down climate change.”

Lobo Mau is tackling the issue of overconsumption head-on by encouraging customers to buy less.

“We’re succeeding if customers are coming to us for an investment piece that they’ll cherish for years and are only doing that every so often,” says Haddad.

His company plans to achieve full circularity by implementing a take-back program and then shredding down those clothes and the fabric scraps in their overflowing bins for use in a new line of home decor and soft home products they’ll be launching soon.

Beyond educating consumers, Fabscrap believes education should extend to designers and brands, and they run programs in partnership with design schools like Drexel University to educate students about the waste that is produced in the design process.

“The program we have with Drexel is the perfect way to challenge them to use what already exists and integrate techniques like zero-waste patterning,” says Fabscrap co-founder Tagle, who leads educational programming. “These are techniques they then can take with them into industry and have the experience to implement those options.”

In their educational programs for brands, they dive deep into what happens when they recycle with Fabscrap so that brands can make better decisions knowing what happens at the end of their product’s lifecycle. Getting brands on board with designing for end-of-life recycling is integral to making it easier for consumers to do their part.

“It’s really hard for residents to act responsibly when it comes to disposing of textiles,” says Helena Rudoff, waste reduction programs lead for Philadephia’s Office of Sustainability. “But collective action really does matter.”

She says that Philadelphia residents can take action by contacting councilmembers to ask for pilot programs that focus on textile waste and better data collection. They can also contact brands they like and ask them to implement take-back programs.

Collective action may be what saves us from our crushing textile waste problem and gets us to a truly circular system that combats climate change. Each organization that touches textiles in some way has a role to play, be it design, production, collection, sorting, reuse, recycling or education. Every individual has a part, too, from changing consumption habits to advocating for circular practices and laws that support circularity.

It remains to be seen how

quickly Philadelphia can make this transition, but there is reason to believe that we will get there. Even though there is still a lot to do, a core group is working on textile circularity with the skills and passion to make it happen.

As McGlonn puts it: “There’s so much work to be done that having one more large organization committed to and working towards change in the region is something we should be celebrating.”

With Fabscrap’s expansion to Philly, one more piece of the puzzle falls into place and the future of the region’s textile system begins to take shape.

From a distance, it looks like a circle.