For decades heroin was the drug that evoked the most fear, but what was formerly known as the “heroin epidemic” has shifted into the “opioid epidemic,” as synthetic opioids and pharmaceutical drugs have become more prevalent. Fentanyl has emerged as one of the most harmful synthetic opiates and has become commonplace among Philadelphia’s drug market.

What is Fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent. Fentanyl was introduced more than 50 years ago. In the early 1990s, the fentanyl patch was adopted as a method for managing chronic pain. Legal fentanyl production can be found in the South Jersey borough of Paulsboro, where British multinational Johnson Matthey has been producing pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl for more than 20 years.

In 2014, before fentanyl became prominent on the black market, the American Pain Society’s “Journal of Pain” noted: “Fentanyl has become one of the most important opioids in the management of pain … Its flexibility, potency, familiarity, and physical characteristics explain why it has become so valuable to clinicians managing pain throughout the world.”

However, illicit fentanyl has seeped into America’s drug supply. According to the CDC: “It is sold through illegal drug markets for its heroin-like effect. It is often mixed with heroin and/or cocaine as a combination product.” The CDC refers to the last seven years as the “third wave” of the opioid epidemic, stating that it “began in 2013, with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl.”

In Philadelphia alone, 950 unintentional overdose deaths were reported through 9 months of 2020, a double digit percentage increase from the past two years. 81% of all drug overdose deaths in 2020 have involved fentanyl, the highest proportion ever reported.

Over the last five years fentanyl has proven to be a mysterious killer among drug users who were addicted to prescription drugs and heroin. Not only has fentanyl affected opioid users, it’s starting to taint stimulants like cocaine and meth, as well as PCP.

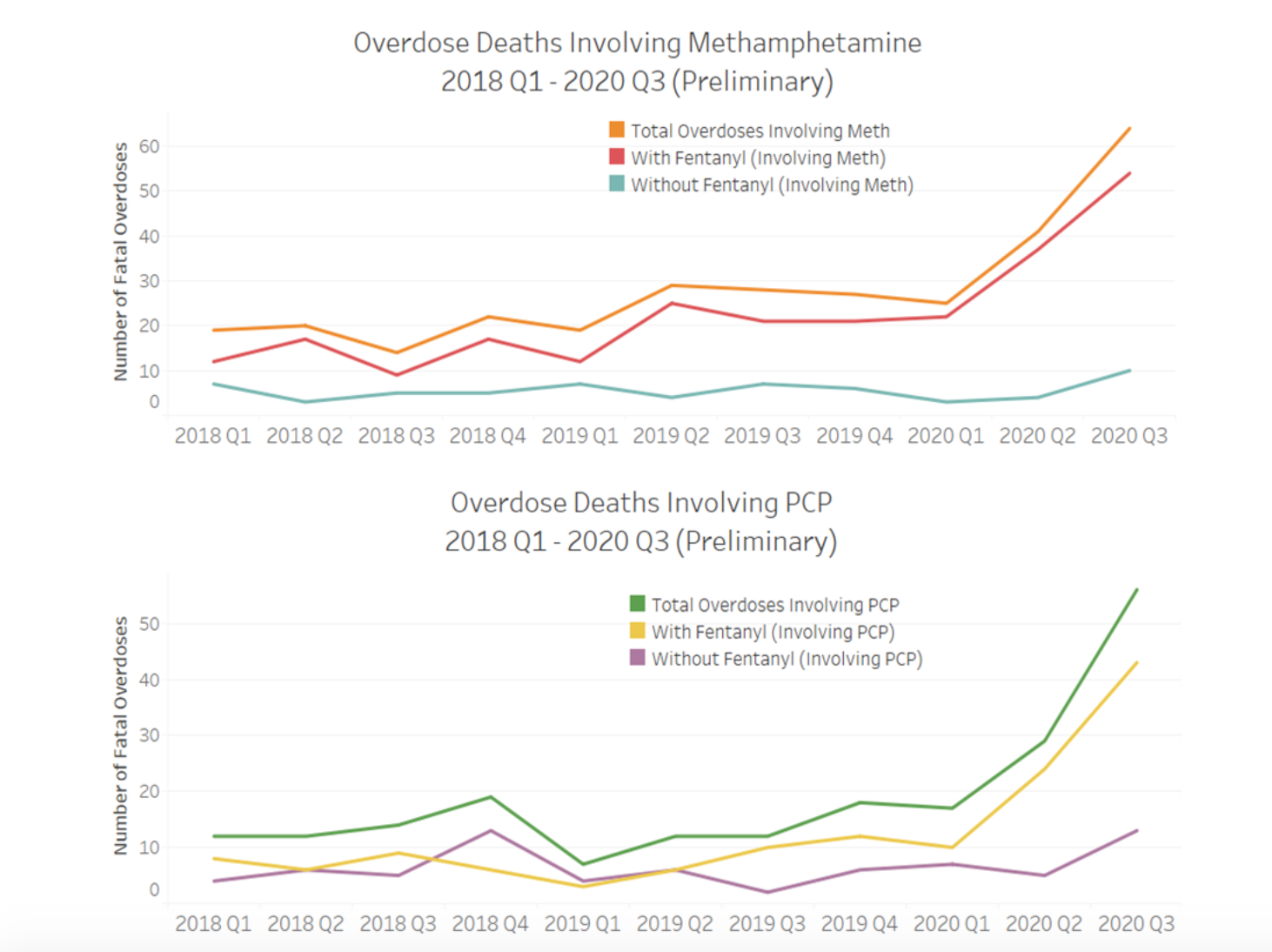

On January 20, 2021 the Philadelphia Department of Public Health released a statement. “From the first quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2020, overdose deaths involving the stimulant methamphetamine in combination with fentanyl increased 350%. Over that same timeframe, deaths involving the hallucinogen PCP and fentanyl increased 1,333%. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 is expected to have had the highest number of unintentional drug overdose deaths of any single year in Philadelphia.”

Fentanyl was a problem specific to opioid addicts, but its presence has spread far beyond Kensington. “Fentanyl is in everything and everyone who obtains drugs from an illicit source is potentially at risk,” says Dr. Kendra Viner, director of the Division of Substance Use Prevention and Harm Reduction at the city’s Department of Public Health.

To get a better understanding of fentanyl we spoke with Silvana Mazzella, who is the associate executive director at Prevention Point Philadelphia, a nonprofit public health organization focusing on harm reduction services, such as needle exchange.

What have been some of the effects you’ve seen of fentanyl in Philly?

SM: Over the last several decades in Philadelphia, as in many other geographies around the country, we had an unacceptable and unfortunate but predictable number of overdose fatalities. We were one of the geographies with the purest, cheapest heroin for decades. We were in the top 2 or 3 around the country forever.

We expect, though unacceptable, a certain number of overdose fatalities, but poly-substance use increases that and access issues to substance use treatment increase that. Fentanyl has changed everything. In 2013 there were 24 overdose fatalities attributable to fentanyl or with fentanyl in the system.

It’s unclear, but we believe that most of those fentanyl fatalities could have been fentanyl patches that were mis-sold, misused, etc., possibly the start of synthetic fentanyl.

You look at 2014, 99 fatalities and then you look at 2015 and it’s a significant percentage. The last full year we had data for, 2019, between 80% and 90% of fatalities have fentanyl in the drug toxicology and over 80% of seizures have fentanyl.

The big difference from 2014 [to now] is synthetical fentanyl. Synthetic one-off chains of fentanyl, one-off [meaning] one slight chemical change per one batch, so it’s untraceable.

You’ve got hundreds of these, you’ve got plans to make [it] online. So you go from a situation of fentanyl being really not a problem to being mass produced and distributed clandestinely and synthetically. Initially in other geographies fairly distant from here, more recently in the last few years there’s evidence of local production.

It’s synthetic and it’s in everything. It starts in the heroin supply slowly adulterating the heroin supply and then replacing it.

We know that there are places in the city where you can buy heroin, very few parts. We know there are places where all you can get is fentanyl and there are parts where you get a mix. We have fentanyl pressed as pills, masquerading as Oxycontin [brand name], oxycodone, or something else.

The next wave beyond prescriptions is fentanyl adultering cocaine, K2 [synthetic marijuana], possibly methamphetamine. All we know, and I’m not law enforcement, but what we hear from law enforcement and hospitals is that all we can know is what someone tested positive for in their drug toxicology, fatal or non-fatal. We cannot know what specific substance killed them.

Another big change is that people report to hospitals, law enforcement and harm reduction programs that they never intended to buy heroin or fentanyl, they’ve never used it willingly. We have to believe that a lot of that is credible. We see fentanyl showing up in drug toxicologies in other parts of the city, in other settings by people who claim to be naïve to opioids.

What percentage of people doing fentanyl know that they’re doing fentanyl?

That’s a great question. I don’t have that answer and I’d be surprised if the health department did. All we can go by is what people tell us as we do outreach or what people tell hospitals.

If you think about three or four Summers ago, [Philly] had a weekend of overdose admissions to hospitals in West and Southwest Philly with cocaine and fentanyl, people claimed they did not know they were buying fentanyl. We’ve had tons of these spikes in Philadelphia where people are interviewed in the hospital saying, “I did not know what I bought.”

We don’t know with fatalities, right? We know that with harm reduction programs as we go out and do outreach, if we do inreach with the syringe exchange, we are obviously reaching out to people who are opioid users. [“Inreach” refers to providing resources to people who are already participants in harm reduction programs.] The majority of people who come to the syringe service program at Prevention Point are opioid users who also use other substances.

Around the country there are differences in what people’s drug of choice is, but through inreach and the syringe service program we know we are getting people that intended to buy opioids or other stuff.

When we do street outreach and give out fentanyl test strips and Narcan in communities where we don’t have a lot of people coming to the syringe exchange, for example; or in communities that have seen a recent spike in overdoses and we talk to people about what they’re using, they’ll say “I’m not taking any of these, I know I’m not taking fentanyl. But something’s different.”

Then when we go back a week later, and ask people, [they] don’t want to fill out a survey about what drugs they’ve used or if they’re tested. Thats a big challenge in all of this.

If you fill out a form admitting that you bought, used and tested your drugs; people are very concerned about opening themselves up to legal [ramifications].

I would never do that.

Exactly, that’s why no one has good data on this. Right? So we go by anecdotal data.

So we say “okay don’t fill out the form but come back next week when we’re out here again at noon and tell us what you found.” People come back and say “you were right, that was not just cocaine – the fentanyl showed up.”

And that’s critical. People beyond harm reduction providers need to be doing outreach.

Is there a segment of the population that wants and seeks out fentanyl?

There is certainly a percentage of the population that wants and seeks out fentanyl, yes. There are a lot of myths about it, there is a myth that everybody wants fentanyl and that is simply not true. I really do believe that’s not true.

But we do know that there are people that were very long-time users that have become exposed to fentanyl and now fentanyl has become the drug they use most often. We know there are people that are long-term users of heroin that want heroin but can’t get it. We also know that there are people that are long term and new users of heroin; that fentanyl offers something different, too, and yes, they like it.

The health department has now done 2 or 3 drug user health surveys. Their own data in addition to ours—off the top of my head, about four years ago something like 46% of new users of fentanyl, so people who weren’t using heroin before they started using opioids, what they got access to is fentanyl. They now seek it out and it’s their drug of choice.

If you go to people who were previously using heroin, that number is lower.

Is fentanyl cheaper than heroin?

It’s way cheaper. But most importantly, it’s all you can buy.

There are a lot of people who choose what they buy, no doubt. There are people who get home deliveries, there are people that have been getting something from someone for many years, but there are a lot of people that are at the mercy of what’s being sold. If that’s all you can find, it doesn’t really matter if it’s cheaper or not. Where are you going to travel to get something that doesn’t exist or exist in the same quantity?

How much cheaper is fentanyl than heroin? I feel like there is confusion in understanding the drug economy.

I mean it could be the same price in some areas, and that’s all you get—you get what you get. It could be half as much. You look at a place like Kensington, people get free samples all the time, people with lower habits can get a lot of free drugs.

If you think about what happened in the service industry recently, how much of that was by choice? You know, it may be, certainly, we know of people that buy speedballs [cocaine mixed with heroin], but don’t believe they’re getting heroin. But all of this data is wobbly.

As an example, we have to rely on what shows up in someone’s toxicology, what they tell us, and then we rely on law enforcement. So we know from law enforcement that the increases in fentanyl in drug seizures and a reduction of heroin in drug seizures also tells us. We know from overdoses, and we know from anecdotes, but we also know, for example, there’s increased methamphetamine. I have to believe that there’s an increase in methamphetamine as a drug of choice, but that there’s also methamphetamine masquerading as cocaine.

When did you see fentanyl for the first time in your work?

2014, maybe 2013. We get all these alerts from different organizations and around that time were all these alerts from Canada. I cannot remember the name of the Listserv we were on, but [it was] all these alerts about fentanyl. So I remember calling their medical examiner’s office, and saying, “Hey, we are not seeing this.”

And they called us back about a month and a half later when they went back in time, they did actually, it was like three in one month, four in another, zero in the next, two in the next. So we were like, “Interesting. Let’s watch this.”

So around 2013 we started hearing, but it really made the jump around 2015.

What do you think that non-opioid, non-cocaine users need to understand about fentanyl that they might not understand?

There is a myth out there that if you overdose on heroin or fentanyl, give someone something else to counteract it. The antidote is Narcan and getting someone medical attention and making sure they don’t use again. But we do know that people that use two and three substances, including completely different types of substances, still overdose, and unfortunately pass away.

Then in terms of education, people need to know how different fentanyl is than heroin or other opioids. It’s 40 to 50 times as potent. It doesn’t matter whether you say you don’t want it or not. It may be there anyway, because that’s what’s available.

People will say to us “Why? I don’t use that stuff, I don’t need Narcan. I’m not like that.” It’s not about being like that. It’s not about being an opioid user or heroin user or fentanyl user. It’s about staying alive.

At the end of the day, people don’t know what they’re getting. Anything could be anything and people need to be prepared with Narcan. They need to. We say start low and go slow.

It could be too late to know what was in your drugs by the time you figure it out, so everybody needs to be armed with Narcan. Everybody knows how to save someone else’s life, everyone carrying Narcan needs to say, “This is where it is. It’s in my pocket, my purse, my medicine cabinet, under the bar.”

There needs to be no shaming of which drugs someone uses. At the end of the day, everyone is at risk for overdose in this era of everything being tainted with something.

Like every restaurant, bar or coffee house—you go to Whole Foods. What do you see in the bathrooms? Sharps containers [for needle disposal]. There’s a reason for that. We need to just stop pretending this isn’t happening and start caring about saving people’s lives.

Access to free Narcan and Naloxone is available here: https://nextdistro.org/philly?mc_cid=5b6c2f4c1b&mc_eid=372659d2fd

If you’re interested in learning more about opioid crisis in Philadelphia, check out the city’s opioid misuse and overdose database: https://www.phila.gov/programs/combating-the-opioid-epidemic/reports-and-data/opioid-misuse-and-overdose-data/