Story Time

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Once upon a time, I met Stephen King.

Perhaps more accurately, I once had an awkward exchange with Stephen King. It was a brief encounter at a fundraiser in New York, and I’m not sure which of us was more uncomfortable during the 20 seconds we spoke. What I remember most about the moment was craning my neck to address him: He is very, very tall.

There had been much debate about whether to honor King at this particular fundraiser for a literary nonprofit—because of that pesky word “literary.” But there he was, milling about the large hall with no handlers, and I wanted to thank him for his stories.

At a smaller party that year, I’d felt like the coolest person in the world to nonchalantly sip a gin a tonic next to lauded poet Philip Levine, but at the side of Mr. King—a commercial juggernaut—I was terrified to say something dumb. As a middle school student, I had eagerly lapped up classics like “The Stand” and “Pet Cemetery” along with the lesser known titles in the “Dark Tower” series. They were accessible to me at 13 in a way that poetry was not. And like the original Grimm’s Fairy Tales, King’s intricate webs were full of sex and death, perhaps not thoroughly suitable for kids but—of course—that was part of the thrill of reading them.

We can argue all day about King’s literary merits: He’s incredibly gifted at creating worlds and drawing you into them, at making you think about the monsters lurking not only under your bed, but in your heart. He’s a master storyteller who knows that (while the deathcount in his novels can be high) a million deaths are a statistic: One death is the stuff of tragedy.

In that regard, advocates ought more often to take a page from the artist’s notebook. Artists, and the art of telling stories, can help get to audiences who will simply never read the numbers-laden program brochures and info-heavy emails that I am certainly guilty of having penned during my nonprofit career.

The writers, actors, dancers and musicians throughout Philadelphia are untapped allies for advocates fighting for just causes. It’s exciting to see that this October, for instance, the Wilma Theater is partnering with Philadelphia’s water department and others during the production of “When the Rain Stops Falling.”

You can hear the alignment of vision in the lyrics of songwriters like Michael McShane, aka Cowmuddy, who can also install green roofs, solar panels and grow a mean tomato. You’ll see it at Fringe Festival shows such as “Jungle,” “Animal Farm to Table,” “In the Clearing” and “Pandæmonium,” which will challenge us to consider what the difference is between man and beast, where our food comes from and how we relate to one another across space and time—a fundamental challenge for climate activists trying to connect us globally, as well as to future generations.

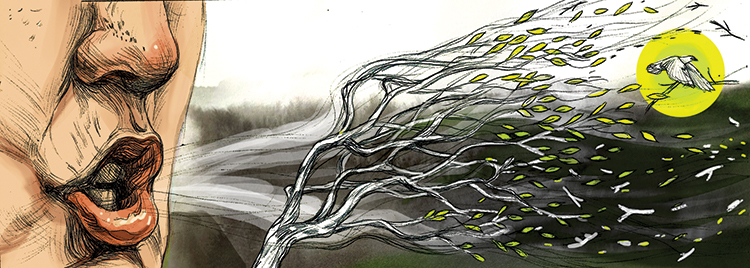

Human beings are deeply attuned to narratives. It’s how we communicate, it’s how we make sense of the world. Writer Joan Didion went one step further and said, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Whether we live, and how well we live, also depends very much on which narrative frameworks we choose in the coming years. Will it be a fairy tale about innovation and technology saving the day in the face of our environmental crises, or will we choose a more realistic reckoning with our patterns of consumption? Will the environment and our economy continue to be pitted against each other for dramatic effect? Will we insist on black-and-white, Disney-fied purity during the transition to a clean energy future?

At the offices of every nonprofit in the city, groups of well-intentioned people are making the mistake of trying to surmount our collective challenges with information and mere statistics. Instead of relying on naked facts, they should learn how to tell better tales.