Audits uncover energy leaks in a Philly rowhome.

Audits uncover energy leaks in a Philly rowhome.

by Will Dean

On a brisk December morning, a white van pulls up outside a quaint, stone-fronted, two-story duplex rowhome in Mount Airy. There are a few people inside, myself included, and some ghostbuster-esque equipment, including fans, various detectors, meters and a big fan. The only invisible thing we’re hunting, though, is heat. We’re doing an energy audit.

An audit is a series of tests an experienced tech can perform on your abode to find out exactly where your house is wasting energy—and costing you money.

Chris Robinson has been doing energy audits for two years and works for the Energy Coordinating Agency, a local energy nonprofit that conducts energy audits and helps low-income residents make their homes more efficient.

He’s a house mechanic and knows that lack of proper insulation is plaguing Philly’s housing stock. “Typically homeowners think their house is drafty because of windows,” Chris says. “Often, it is actually lack of insulation.”

Chris starts the audit with some questions about bills, any obvious problems (like a leaky roof) and when work was last done. Then he breaks out the equipment.

There’s a lot of science to an energy audit; it’s like a check-up for your house, complete with fancy gizmos and meters and prescriptions of how to fix things.

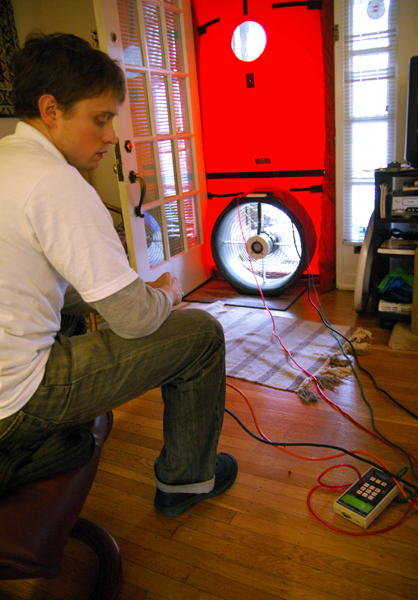

Chris opens the front door, sets up a frame and covers it with a sheet of red plastic with a round hole for an industrial fan. This is the blower door test, which is used to find leaks in the house. The fan rumbles to life and a slight breeze picks up and lightly brushes my face. Checking a glowing green readout on a handheld pressure sensor, Chris half-shouts, “We’re depressurizing the house to -50 pascals [a unit of air pressure] so we can find out how much air usually moves in and out of the house.”

He leads us up the stairs to explore the leakiness of individual rooms. With the fan pulling air out of the house, outside air rushes in and any leak is magnified a hundred times.

The bedroom, which the homeowner says gets very cold, is pouring enough air into the hallway to ruffle hair. The problems in the room are like many houses in the city. Old jalousie windows—which have multiple overlapping panes and often date back to the house’s construction in the late ’20s—are leaking cold air. In addition, the entire room is a knee wall joint (see sidebar), and the baseboards are not well-insulated. A window-mounted air conditioning unit lets more air in through its vents.

After we check the furnace and hot water heater for efficiency and safety, and look at a few more obvious leaks, Chris makes some recommendations. Later he will write up a report for a contractor to fix the drafts.

Even with the bedroom leaks, the house is in pretty good shape, thanks to the benefits of the most common Philly housing design, the rowhome.

Shared walls are always good for efficiency, and the simple unadorned construction can be very effective if sealed properly. The most efficient house Chris ever saw was a small rowhome in North Philly. “It was just this little box rowhome in Kensington,” he says. “I did all the tests and told her, ‘Well, there’s nothing I can actually do; you’re doing great.’ ”

For the most part, though, Philly’s aging house stock could use some help, and energy audits are the best way to start. The ECA estimates that many homes in Philly could save up to 60 percent off their bill by tightening the building envelope. A lot of that is in simple insulation fixes and replacing aging components.

You might be able to find help, too. The ECA is part of a federal pilot program called Home Performance with EnergyStar that funds the first 50 energy audits if the homeowners start repair work. They hope Pennsylvania will fund energy audits in the near future.

Even if you do end up paying for it, the savings on your bills will make up for the price in a couple years. They might let you use all the cool equipment, too.