Myriam Siftar cried tears of joy.

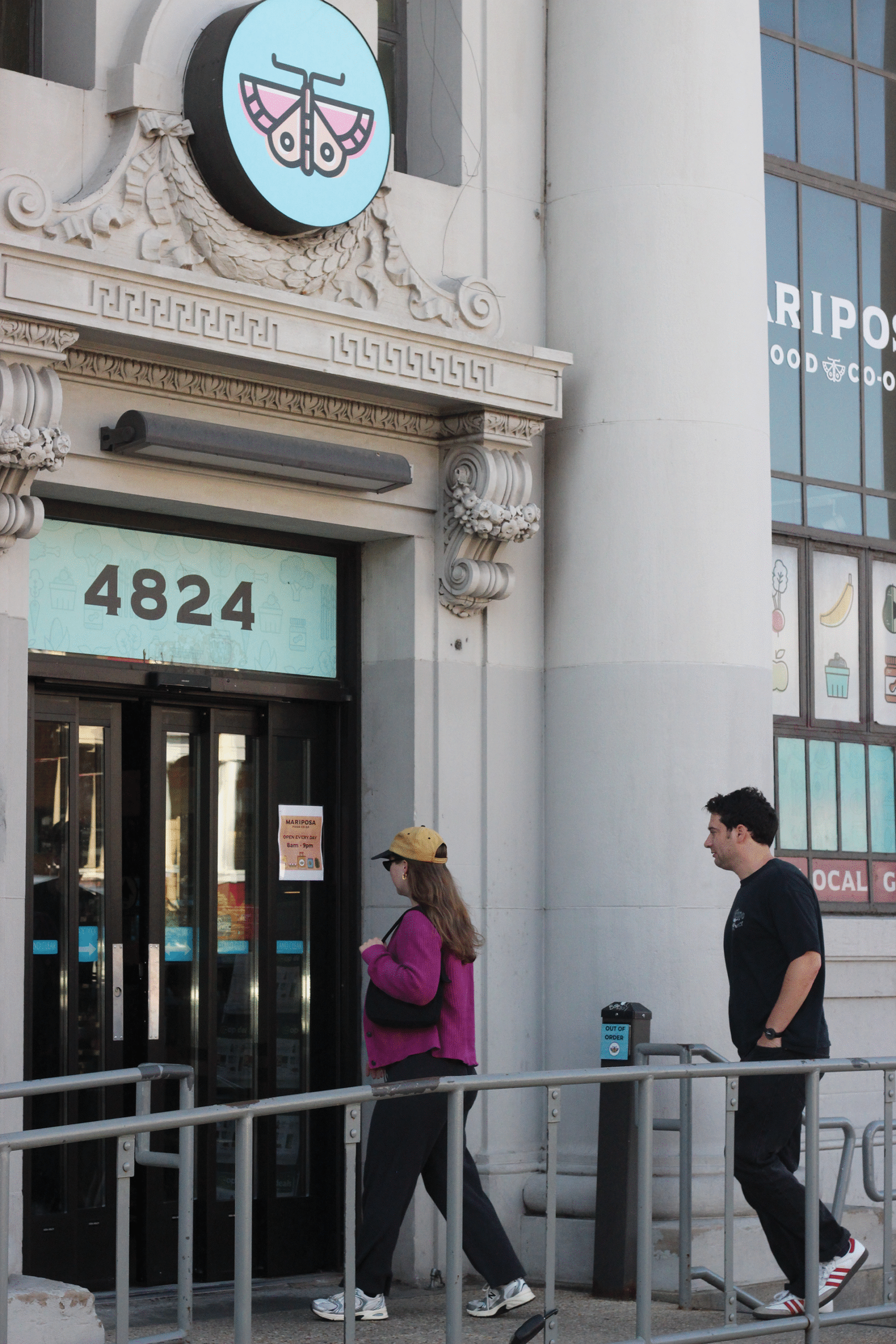

It was March 2012, and she was at the grand opening of Mariposa Food Co-op’s new home, a Greek-revival style former bank building on Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia. (Full disclosure: This author is a member of the co-op.)

For Siftar, it was the triumphant culmination of a journey years in the making. Originally founded as a buying club distributing out of basements and garages in 1971, Mariposa — like many co-ops that formed around that time — was meant to serve as an alternative to the growing corporate food system, with an emphasis on democratic control, local goods and community participation.

By the time Siftar moved to the neighborhood in the early ‘90s, Mariposa had bought a storefront at 4726 Baltimore Avenue and merged with another co-op. Like other members of the co-op, she had a key, and she’d simply let herself in to do her shopping. In the early 2000s, just after Mariposa hired its first paid staffer, she served on the personnel committee and helped develop the co-op’s first human resources policy.

In the years since, she’d observed the co-op’s growth with excitement. By 2008, lack of space forced Mariposa to start a waiting list for new members and begin looking for a bigger space. The co-op’s new — and current — location, nearly five times larger than its former location, was the space they’d need to accommodate their 1,300 members and accept everyone on the wait list. The space would allow the co-op to actively recruit new members for the first time in its history, expand guest shopping for non-members, place larger orders and offer lower prices. In an area formerly a fresh food desert, it also felt like a victory for social justice. “I thought it was amazing what the community, the board and the membership had done. Truly amazing,” says Siftar.

In the decade after, she continued to shop at the co-op, but didn’t keep up with its goings-on. Then, in 2022, Siftar spotted a flyer for a newly-formed group called Mariposa Liberation. Curious, she took the flyer and attended a meeting. There, she discovered that a lot had changed at Mariposa over the years, in ways that some people believed disempowered workers and member-owners alike.

In the years that followed, the attempts of both member-owners and staff to reclaim control of the co-op would ignite longstanding and ongoing debates within the food co-op movement: What is a co-op for? How should it operate? And perhaps, most importantly, who has the power to decide?

Back when Mariposa was a members-only co-op in a small, 500-foot space, all decisions were made through universal consensus by membership. “At the time it was kind of a stranglehold model where anyone could veto any proposal,” says Andrew Zitcer, a longtime Mariposa member-owner and a professor at Drexel University whose book, “Practicing Cooperation: Mutual Aid beyond Capitalism,” considers Mariposa and other co-ops in Philadelphia. As the co-op grew, he remembers, that model couldn’t last. “It’s really hard to have hundreds or thousands of people giving input on decisions that have to be made within hours or by the next day,” he says.

When the co-op started hiring staff — by 2005, there were five of them — they began managing store operations as a collective. In 2009, Mariposa created a board of member-elected volunteer delegates to make big picture decisions. Shortly before the move to the new building, the board created an operations committee (OC), staffed by department coordinators, to support the staff collective.

But both the staff collective and the OC had problems with the arrangement. According to Jamila Medley, who joined Mariposa as membership coordinator in 2012 and served on the OC, members of the committee were not compensated for their work, and most didn’t want to serve. Since the committee’s role was ill-defined, and the rapidly growing staff collective wasn’t trained to take on management responsibilities, the work kept piling up: the group came to be responsible for everything from determining whether a CSA could drop off boxes at the co-op to hiring a personnel coordinator.

Something had to change, but the way forward wasn’t obvious. In 2014, Medley and another OC member, Sam McCormick, proposed a new management structure: a two-person interim management team — Medley and McCormick offered to take on the roles — to “lead Mariposa’s staff through a transformational period after which it will have a workplace that is reflective of the democratic values identified by the Staff Collective.”

Tomason Payne, a staff member since 2005 and a former OC member, was concerned about the proposal. The OC, they say, had become increasingly out of touch with the sales floor due to the overwhelming workload. Further concentrating decision-making power in a couple of staff, they worried, “would run the risk of isolating management even further, making collective responsibility more elusive at the moment it is most necessary.” So they developed an alternate proposal with a handful of other staff members to redistribute operational responsibilities across separate committees, “rather than looking to only a few staff members to do everything.”

The board voted, Medley’s proposal won out, and immediately sparked backlash. Some staff members, Medley recalls, even organized a special membership meeting to have the decision of the board overturned. In the meantime, Medley began implementing a year-plus-long plan to guide staff in determining a new management structure for the co-op. But she says it struggled to move forward. “Some of the staff members who were called into supporting that work just didn’t do it. Meetings would get scheduled and people wouldn’t show up,” she says. Ultimately, the process proved so difficult, she resigned before it was complete.

“I learned a lot at Mariposa. And I think one of the important things that I learned about democracy is that it’s extraordinarily messy and it’s soul-sucking and it takes a lot of work,” Medley says.

Shortly after Medley left in 2015, her co-interim general manager, McCormick, left as well. A long-term staff member took on the role of interim general manager that same year with the idea that he would soon make way for a longer-term transitional general manager. “As I understand it, there wasn’t an alternative,” says Medley. “So I think the board defaulted to it.”

In 2016, Mariposa looked beyond its current staff to hire a new manager. It found Aj Hess. Hess had been working in co-ops for decades, since they started volunteering at the People’s Intergalactic Food Conspiracy in North Carolina.

According to Payne, who served on a committee of staff and board members charged with coming up with a new management structure for the co-op, Hess was hired to finish the process Medley started: help the staff manage the store. A job description for the role reviewed by Grid shows that the hire was meant to “meet targeted goals for transition to Self Management.”

“A big part of what we hired Aj to do was to support and oversee the implementation of this new structure, and we wanted to ensure it would be fully established and operational by the end of their three-year contract,” says Payne.

Hess has a different recollection. They say their remit was to help “determine the management structure that would be put in place.” After conducting staff surveys and “observing a lot,” they say it was “clear that there was only a small segment of staff who actually were interested in collective management,” and a larger majority “wanted some sort of democratic workplace, but [felt] that collective management wasn’t necessarily the direction.”

Six months after Hess’ hire, collective management came off the table entirely. In September, the board voted to adopt policy governance, a governing model for co-ops developed by the consulting firm Columinate (formerly CDS Consulting), which provides consulting services for Mariposa and “exercises a near monopoly on board training and education in the food co-op movement,” according to In These Times.

Under policy governance, according to Columinate, “governing boards establish their values and expectations in policy, delegate implementation to the board’s sole employee (typically the general manager) and monitor the outcome of operational activities against the stated policies.” In short, it put operational control of the store squarely with Hess.

Some people think only direct democracy is cooperative.”

— Andrew Zitcer, Drexel University

This is not unusual. Weavers Way, a Philadelphia food co-op that has been in operation since 1973, also uses policy governance. According to Zitcer, policy governance has become the standard for most co-ops nationwide. But the model is not without its critics. “Some people think only direct democracy is cooperative. So if I as a member don’t want the co-op to sell red grapes, and they do, and I didn’t get to make that choice, it’s not a democracy,” says Zitcer. But most people, he says, “don’t want to be involved in the day-to-day,” and are content to cede a level of democratic participation as long as they can be assured their co-op is an “ethical place” that is “serving the community and the members.”

“I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with policy governance,” says Zitcer. “I think the question is: ‘Who’s watching it?’”

In the years since Mariposa adopted policy governance, the model’s effectiveness has been an open question. Those questions became pointed in September 2018, when a group of more than 20 current and recently departed staff members wrote a letter addressed to the board, member-owners and the broader community. “The ineffective, unsupportive, divisive and overall poor management style enacted by Aj Hess has directly contributed to high staff turnover, abysmal staff morale, inefficient store functioning and financial risks incurred by both the co-op itself as well as our member-owners,” the authors wrote.

The letter included a bulleted list of 18 grievances directed at Hess, among them: “fostering a culture of fear, intimidation and retaliation,” “failure to publicly disclose money skimming affecting shoppers and member-owners,” “undisclosed and nonconsensual surveillance of staff and member-workers via video cameras installed in work areas without staff knowledge,” and “failure to work toward returning to staff governance by the end of their contract, a stated duty and objective of their job description upon hire.”

According to the letter’s authors, they’d made efforts to “communicate concerns to the Board and to resolve these issues internally with little to no action taken.” Now, they were publicly demanding the board remove Hess from their position, speed up the process to install a permanent general manager and help come up with a new management and governance structure that “empowers staff in collective decision-making.” (Hess says they only became aware of the letter recently; they declined to comment on its contents.)

The letter did not have its intended effect. Although the board acknowledged staff dissatisfaction and opened hiring for the manager role to outside applicants, in January 2019 it unanimously voted to offer Hess the permanent position of general manager. Three years later, the board would approve a new title for Hess: “Co-op Executive Officer” or CEO.

In the years after Hess’ hire, some Mariposa workers remained determined to exercise greater control of the co-op. Will Inglis was hired as a stocker at Mariposa in July 2019, and at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, he started organizing with his coworkers on the floor staff to demand hazard pay. That effort transformed into a union campaign, which resulted in a contract in March 2022. Inglis served on the organizing committee and the bargaining committee, and eventually became the shop steward for floor staff. “We intend to make Mariposa a workers’ paradise. We’re going to make it a place where you can make a good living. This first three-year contract is step one. We’re going to seize control of the place, the people who work there, through the board, and we’re going to run the place,” Inglis told The Philly Partisan. (Hess fired Inglis in 2023, and after detailing his negative experience with management at a member meeting, he got a letter from Mariposa’s lawyer threatening legal action for accusing Hess of “wage theft” in a public setting. The letter also informed him he was banned from the co-op for life.)

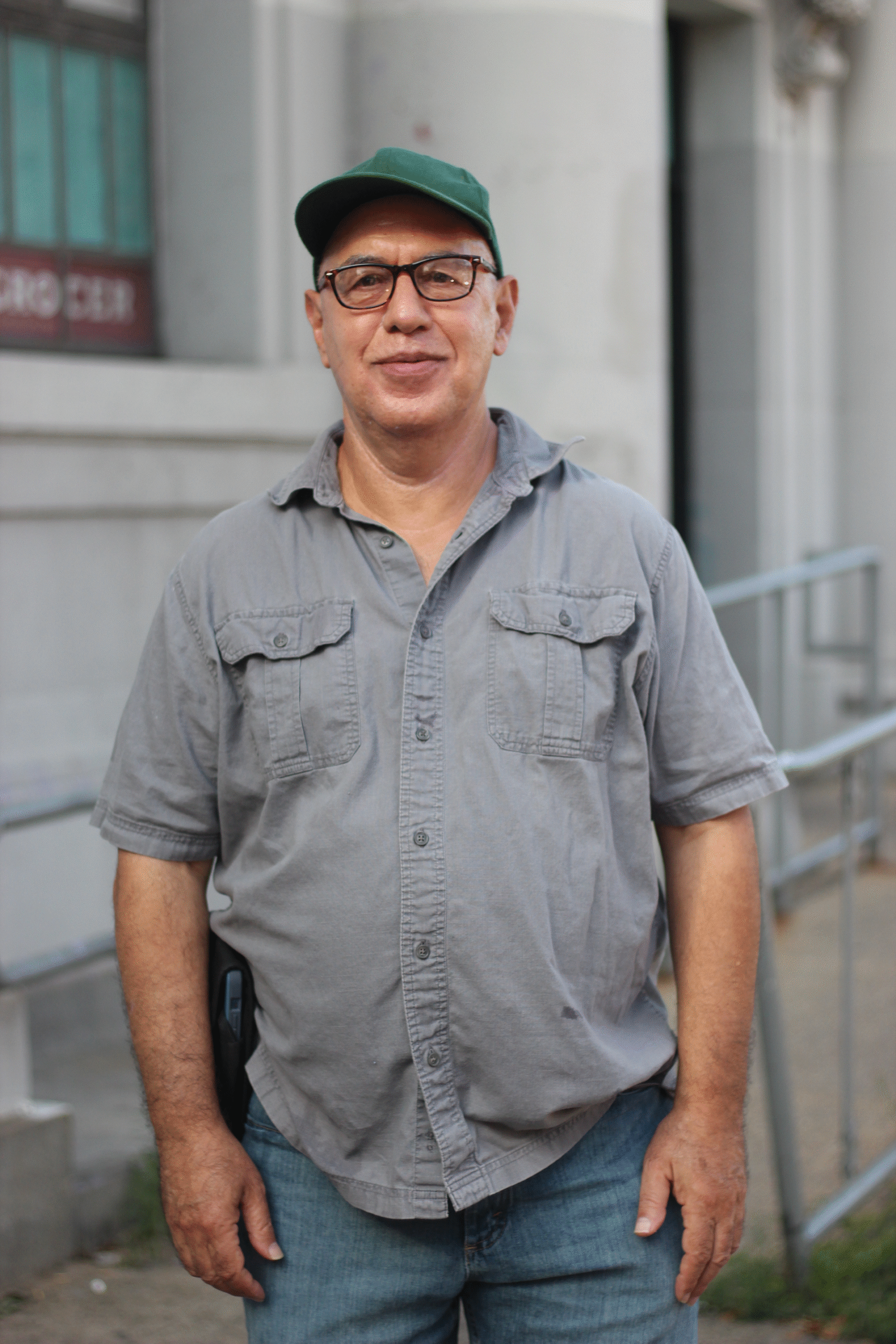

The efforts of staff eventually dovetailed with those of member-owners like Austin Kelley. Kelley had been involved with the co-op movement since the 1970s, when he participated in the People’s Food System, a series of worker-owned collectives in the Bay Area. “I had experienced a different model that’s more about participatory power within the collective and worker dignity,” he says.

In 2022, when he found out Mariposa’s staff had formed a union, Kelley began organizing fellow member-owners, including Siftar, to advocate for them. Together, they talked with member-owners outside the co-op and attended board meetings. While Kelley’s concerns about the co-op initially stemmed from labor conditions, they quickly expanded. In an open letter sent to Hess in July on behalf of other member-owners under the umbrella of Mariposa Liberation, he decried a lack of transparency around Mariposa’s finances, labor policies and operations. “The future of our Co-op should be one that keeps Mariposa accountable to the greater community, clearly based in cooperative principles and social justice values generally, centering worker rights in particular,” he wrote.

Their concerns are not unique in the co-op world. In 2016, member-owners of La Montañita Food Co-op in New Mexico organized a “Take Back the Co-op!” group to reclaim democratic control, according to In These Times. Around this time, member-owners of the Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany, New York, organized a similar campaign to “wrestle back their co-op from a board that was working with the management team to strip authority from the membership.”

In the summer of 2022, Mariposa Liberation organized a series of public forums to discuss their concerns. Hess attended one of the meetings in August and took questions from attendees. “It was a bit eye-opening that we still had engaged members because, prior to that, members were never showing up to board meetings. We very rarely had contested board elections,” Hess told Grid. “That showed me that there were people who wanted to engage at a bigger level.”

According to staff, Mariposa Liberation’s efforts didn’t lead to improved conditions at the store. At the beginning of 2023, a group of current and former staffers once again sent statements to the board detailing additional complaints against Hess, including fostering a “toxic work environment” characterized by harassment and bullying. The staffers called for Hess’ removal and “the establishment of a committee, inclusive of union floor staff, to create a new management structure for the co-op.”

Alex Millard, a former staff member who had worked at Mariposa in 2018 when staff called for Hess’ removal, also wrote a letter. “It pains me to see that Mariposa is still having so many of the same problems with staff turnover and unhappiness that it was having five years ago,” Millard wrote.

Board members were confused about how to proceed. “According to the policy governance model, how is the Board supposed to respond to a significant level of dissatisfaction with management? Hether [Mariposa’s Columinate consultant] suggested that we ask Aj to reach out to staff to rebuild trust,” one board member, Elaine Fultz, wrote in an email to her fellow board members. “Is this the optimal approach in a situation where nine staff members are calling for their resignation? Should we be doing something in addition to that and if so what?”

In a group statement sent to The Philadelphia Inquirer by then-board convener and former Mariposa marketing and communications manager Meaghan F. Goodwin-Washington, current board members said they were “deeply concerned” about “dissatisfaction” they’d heard from about a third of the staff, and had, as a result, instructed Hess to complete an anonymous staff survey (already an annual requirement). According to a July 2023 document written by Hess reflecting on the survey’s results, “results indicate we have not met all the benchmarks” for a “minimum acceptable rating” set by Mariposa’s Columinate consultant. “At the time of the survey, there was quite a bit of negativity in and around the co-op,” Hess wrote, noting that “all of the questions had a high standard deviation, which really demonstrates the inconsistencies and shows that staff were having very different work experiences.”

Since the staff survey, the report mentions, Hess had attempted to make improvements including open office hours, a periodic “Positive Vibes Wednesdays” initiative and the introduction of “staff appreciation vouchers.” Hess wrote that “there has been a palpable shift in vibes and energy at the co-op. In addition to the changes we’ve already implemented, the managers and many staff members have really been working on and committed to change the culture and morale.”

What further action was taken by the board is unclear. In a statement to Grid, Goodwin-Washington says that she “does not remember much that went into the process when the staff was unsatisfied.” She does recall encountering hostility from staff and efforts from the membership to “undermine” her leadership and that of the board. She also felt that “as a Black woman, I was putting out tons of emotional labor for an organization who elected me but didn’t feel I was worthy of leading.”

Hess declined to comment on the specifics of the letters of no confidence. “Sometimes you’re going to have staff that are unhappy. And if the board had larger concerns, they have avenues that they could go through to do further investigation, but at this point they have not, and they have determined that there’s nothing substantiated,” they told Grid. The staff, they point out, are unionized, and “if there were larger concerns, the union would bring them to me and that’s the staff’s process. The staff’s process is not to go to the board or to the press. It is to go to their union. And if nothing is coming out of that, then that indicates to me that, again, none of the claims are substantiated.” (According to Hess, the 2024 staff survey shows staff morale has improved substantially. “We saw tremendous improvement in the staff survey, to the point where the survey administrator said that she had never seen such remarkable results,” they say.)

Hess remained in place, and member-owners continued to organize. In April 2023, Kelley ran for the board and won a seat, and in October, Kelley’s group, now known as Friends of Our Co-op, gathered petitions to initiate a special membership meeting. Nearly 50 members, staffers, board members and members of management attended. In a wide-ranging conversation, members discussed concerns about a lack of financial transparency, low staff morale and unsatisfactory shopping experiences. They decried a decline in member participation, including the working member program — in exchange for volunteering at the co-op, members could get a discount at the store — that ended during the pandemic and never returned. Taken together, these concerns, a report by Friends of Our Co-op found, “present a serious and unfortunate picture of financial risk, deterioration of shopping experience and erosion of satisfaction and confidence for members and employees.”

After the meeting, Kelley says, he continued to commit himself to improving the co-op. But he often found himself at odds with the status quo of “deferring to executive power and executive privilege.” Ultimately, his time on the board was short. Three months after the meeting, the board voted to remove him due to “violations of the board code of conduct as well as numerous other board and co-op policies,” which he says were never explained to him.

Can Mariposa’s board hold its CEO accountable? Kelley, ultimately, thinks not. He believes that the limitations of policy governance results in a board “deeply out of touch with autonomous worker voices as well as independent, grassroots member concerns relating to the structures and processes that shape and define our co-op.”

Kitty Jauregui, who in the past has been affiliated with Friends of Our Co-op, agrees. When she joined the board in April 2024, she says, she found it to be weak and passive, ill-equipped to effectively oversee Hess. The loss of institutional knowledge resulting from board turnover over the years meant that new members didn’t have a sufficient understanding of their roles. Ultimately, she found, the board had gradually ceded much of its authority. It had skipped reviewing crucial financial reports. It had neglected to complete an annual performance review for Hess on several occasions. Board members had no way to get in touch with the entire co-op membership; they neither had an email list of membership, nor the ability to update Mariposa’s website.

The board doesn’t know its own power.”

— Kitty Jauregui, past affiliate of Friends of Our Co-op

“The board doesn’t know its own power. Because of all the turnover, new board members look to Aj because of their experience. But ‘Can we do that?’ turns more into asking for permission than advice,” Jauregui says.

In recent years, Jauregui found, the co-op had been falling behind on finances, membership and staff retention. Mariposa’s employee turnover rate, she found, was around 85% two years in a row. In six out of the last seven years, it had failed to meet its targets for membership growth, meaning it was 1,000 members below its goal. Sales, she says, had fallen more than $2.5 million in the previous five years, and the store’s cash position had declined more than 50%, bringing the store close to a point where it would be “not enough to cover the investments our members have made in the co-op.” When Jauregui raised these concerns to her fellow board members in an email, she was met with silence.

“The pandemic really hurt our sales, with new stores opening up in the area and making improvements in their stores,” says Hess. “I believe that some of the negative press has not helped us either. But overall we are still doing well. We’re still meeting a lot of our benchmarks.”

Jauregui’s time on the board, like Kelley’s, was short-lived. That fall, her partner, Tim Reimer — a longtime critic of Mariposa on social media — posted to Reddit about the co-op’s declining sales and cash reserves and called for Hess’ firing. Jauregui shared the post. In November, the board voted to remove her from her position, and to terminate Reimer’s membership.

There are good reasons why many co-ops have chosen to empower their general managers, says Jon Steinman, the author of “Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants” and the former board director of the Kootenay Co-op in Nelson, British Columbia. “Policy governance became as important as it is today because there were so many instances of general managers not being able to do their job because the board was trying to get too involved in the operations of the store,” he says.

In today’s highly competitive grocery market, he says, many co-ops wouldn’t survive without a general manager given as much leeway as possible. “Ideally, the general manager is an expert at what they do and the board’s job is to find that expert, make sure that they’re meeting the standards that are set by the board and allow that general manager to do their job well.”

That ideal scenario, he says, doesn’t always play out, and policy governance can create more separation between the member-elected board and the store. But it doesn’t have to be that way. He says co-ops using policy governance can still effectively serve members’ needs and values through innovative engagement. “For a co-op that isn’t deeply engaged with its members, it probably has little to do with policy governance and more to do with there simply being a lack of skill, creativity or capacity among leadership at the operational or board level.”

Co-ops that don’t use policy governance, Steinman says, still experience interpersonal strife and often suffer financially. But there are some notable exceptions. The Olympia Food Co-op in Washington, for example, does not have a general manager; instead it’s operated by a non-hierarchical collective of 80 staff members, which makes decisions by consensus. “It’s not efficient in the very literal sense of the word, but the long-term payoff is worth the technical inefficiency of running collectively,” says Becca Bolo, who runs the bulk department. According to Bolo, the co-op is growing, with two retail locations and plans to expand.

Lew baum, for one, believes Mariposa should stay the course. He worked as a member-owner volunteer in 2018, and got re-engaged in the co-op through the Friends of Our Co-op group. He began serving on Mariposa’s board last year and became convener this June. (His views, he tells Grid, do not represent the board.)

“It would be a big and risky job to rebuild our structure and a functional culture without policy governance,” Baum says. “Policy governance is not holding us back, and spending time on it now would be a wasteful diversion from the core issues — bolstering our finances and engaging our members and the wider community.”

“Some people think that if we got rid of Aj, everything would be ducky,” he adds. “I think that’s very naïve.” Mariposa’s issues, he says, go deeper than personnel and management structure, and are tied to wider economic forces: inflation, the lingering impacts of the COVID pandemic and increased competition from corporate grocery consolidation. “We can work collaboratively with the executive. And ultimately, if we don’t like what’s going on, we can simply pass new policies that require the executive to do what we feel is necessary,” he says.

The board, under his leadership, is making progress, he says. It’s working on a performance review for Hess, and formalizing processes for monitoring the co-op’s finances. “The board is much more active now, and we are working more productively among ourselves and with management,” he says. “The Board has written plans and priorities. More is getting done in our committees. Finances are slowly improving. There is more to do.”

Siftar is less optimistic. While she wishes Mariposa well, she says she doesn’t recognize the co-op as it exists today. Organizing with Friends of Our Co-op, she says, is at an impasse, and she can’t imagine a path toward a future for Mariposa that resembles the place she once knew and loved. “If we can’t be a co-op anymore, then let’s just say it. Let’s not pretend,” she says.

Zitcer, however, believes Mariposa — and all cooperatives — always have the capacity for change. “I think it’s still in a transition that we could trace back to 2012 or 2015. And that’s the beauty of a cooperative, like the beauty of a democracy: so long as the structure of participation is intact, it can be re-imagined. I believe that cooperative structures always have that potential,” he says. “Instead of an organization, we have to think of it as organizing. It never stops.”

Just a small correction: I am no longer affiliated with FooC. Thanks for all your work!

Lew has missed the point entirely. Getting rid of AJ was supposed to be a first step not a cureall. It’s been long enough we can no longer use the pandemic as an excuse for the poor sales and employee retention. There are too few who feel like part of the “we” who can work with the executive. Actually it is the “executive” who doesn’t care to work with “us.” AJ has singlehandedly destroyed the sense of community the co-op used to be. There used to be a library and meeting space upstairs and they’ve closed it off. The pandemic ended volunteer workers, but AJ keeps preventing them from coming back and the board is letting them. Now it is a cooperative in name only.

It is right that we find out the details of the CEO package- passed behind our backs and without our collective consent- by a former iteration of the Mariposa Board. It is right that we in the community get to say whether we agree with this key element of the current power structure.

In addition, it is only right that we get to hear about the many, many questionable actions that have occurred over the last 10 years of the CEO’s rule- some but not all described here- and get to speak directly for ourselves about whether we consent to and approve of Aj Hess as Mariposa CEO.

If it were not for some of the built in features of the current status quo, this would have all been done long ago.

If being a co-operative means anything, it should mean that the ordinary people who make up the co-op: workers, members and others, get to directly participate in consenting to the main issues that frame, define and provide everyday structure to that co-operative. We should expect- and demand- nothing less.