It’s a balmy day in late August, but the Mycopolitan Mushrooms grow room feels more like a forest floor in mid-October. A thick mist sprays from the ceiling, casting a glowy haze across shelves filled with blooming oyster mushrooms, lion’s mane and a handful of other exotic species.

Pennsylvania is home to the majority of the country’s mushroom production, with most farms concentrated in Chester County. But, strangely enough, instead of Kennett Square, Mycopolitan co-owner Tyler Case drives into the Juniata Park neighborhood of Philadelphia to his farm.

“It’s bizarre, but it makes sense for a mushroom farm to be here,” says Case of the subterranean production space in the basement of the Common Market building. The earliest mushroom farms were in caves, and with an apparatus of lights, misters and air conditioners, Mycopolitan has created a strikingly cave-like environment where mushrooms can thrive.

“Mushrooms, in nature, make use of unused space and refuse,” says co-owner and production manager Dan Howling. “I feel like the basement is sort of like that — it would otherwise go unused.”

Case and Howling, along with co-owner Brian Versek, started building this grow room in 2013, and officially started growing and selling their exotic gourmet mushroom varieties under the name Mycopolitan Mushrooms in 2014.

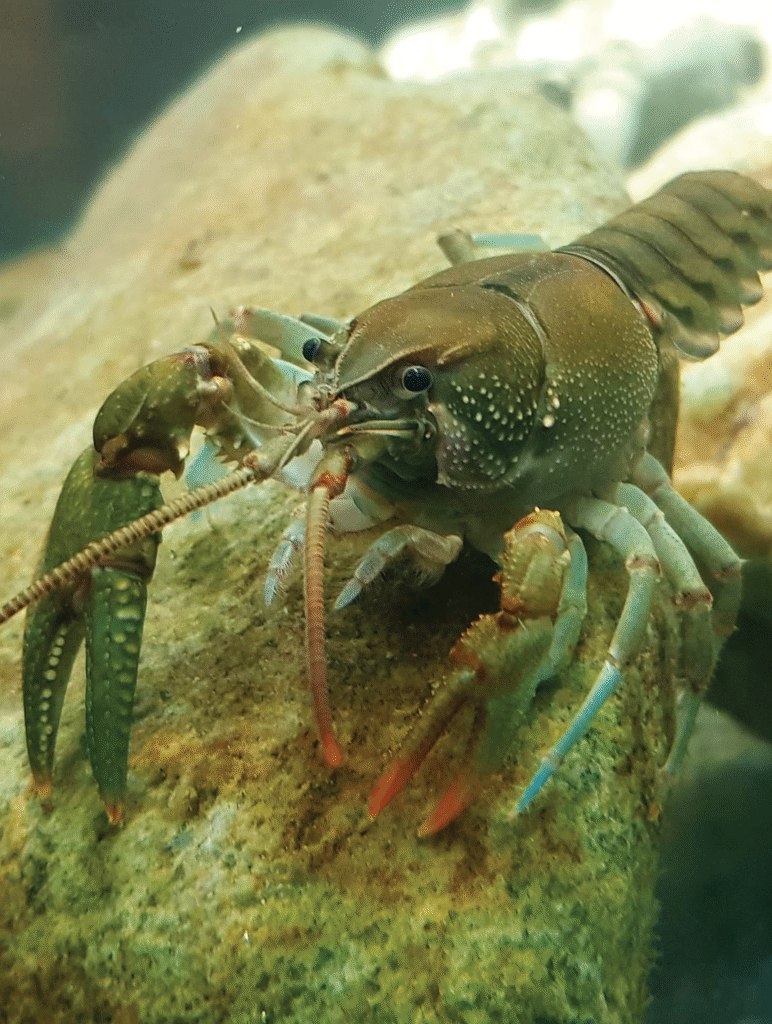

The grow room currently holds eight mushroom varieties sprouting from substrate blocks: blue oyster, Phoenix oyster, shiitake, chestnut, Pioppino, lion’s mane, coral tooth and reishi. But in the cooler months, Mycopolitan operates a second grow room to make room for increased production and seasonal varieties like golden enoki, king trumpet and black pearl oyster mushrooms. Here, you won’t find commercial varieties like creminis or portobellos.

“We’re more artisanal compared to some of the more massive farms, which means that we can have a higher attention to detail: we can harvest at the perfect time, refrigerate immediately, [and] get it out to our customers as soon as possible,” says Versek.

Case first came up with the idea of starting a mushroom farm while working with Versek at a previous job. As Versek tells it, the whole process of starting the farm came together in just a few months. They put their idea “out into the universe” — on a now-defunct urban farming listserv — and quickly got connected with nonprofit food wholesaler Common Market as they were moving into the Erie Avenue warehouse. Soon, Mycopolitan became the building’s first tenant.

“They immediately recognized, almost casually, to themselves, somebody should be growing mushrooms in this basement,” says Versek.

Over a decade later, Case and his team have refined the entire process for growing mushrooms, down to the substrate. Each block of mushrooms starts off as an 11-pound plastic bag filled with a wood-based substrate. Every day, staff members fill at least 60 bags with pellets of red oak sawdust and soybean hulls before hydrating them and preparing them to be sterilized.

Once the bags have been cooked to about 98 degrees Celsius [208 Fahrenheit], they are cooled, then inoculated with mushroom spawn. The bags are then taken into a dark room where the mycelium — the branching structure that makes up fungal colonies — can grow. The mycelium consumes the substrate block in its entirety, growing itself in the process.

Once the bags are fully myceliated, they are ready to be moved into the grow room and cut open to sprout their fruiting bodies, the actual mushrooms. And in a few days to a couple weeks, depending on the species, a full flush of mushrooms will have grown and be ready to harvest.

The leftover material is actually wonderful stuff. It’s high mycelial biomass, which everything wants to gobble up and turn into really fertile soil.”

— Tyler Case

Much of Mycopolitan’s real estate is taken up by shiitake blocks, which take around three months to incubate, much longer than most other species they produce. Once ready, the shiitake mushrooms themselves can grow in seven days, Case says.

“Eight months out of the year, we have probably about 2,700 blocks in this room,” says Case. The incubation room takes up the length of the basement — 150 feet of shelves in near-darkness. Case quickly calculates: “there’s about 15 tons of mycelium in here.”

Mycopolitan produces an average of 900 pounds of mushrooms per week in the summer, and as much as 1,500 pounds during the rest of the year, spanning their 12 unique varieties.

“There’s a lot of different flavors in here, but all of them have umami,” says Case.

Flavor is huge at Mycopolitan, which supplies mushrooms to over 20 restaurants in the Philadelphia area. Case and Versek throw out words like “cheesy,” “porky,” “musty” and “nutty” to describe the aroma and taste of each species.

Mycopolitan also distributes to locals through a farm share subscription program. After harvest, the spent substrate blocks are composted or donated to community partners.

“The leftover material is actually wonderful stuff,” says Case. “It’s high mycelial biomass, which everything wants to gobble up and turn into really fertile soil.”

Mycopolitan Mushrooms can be found at the Phoenixville, Wyomissing, Downingtown, Malvern, and Collegeville locations of Kimberton Whole Foods, with fresh deliveries weekly and available for purchase every Friday. “We’ve had a great relationship with Kimberton Whole Foods. They’ve really drummed up a lot of interest in lion’s mane,” says Case.