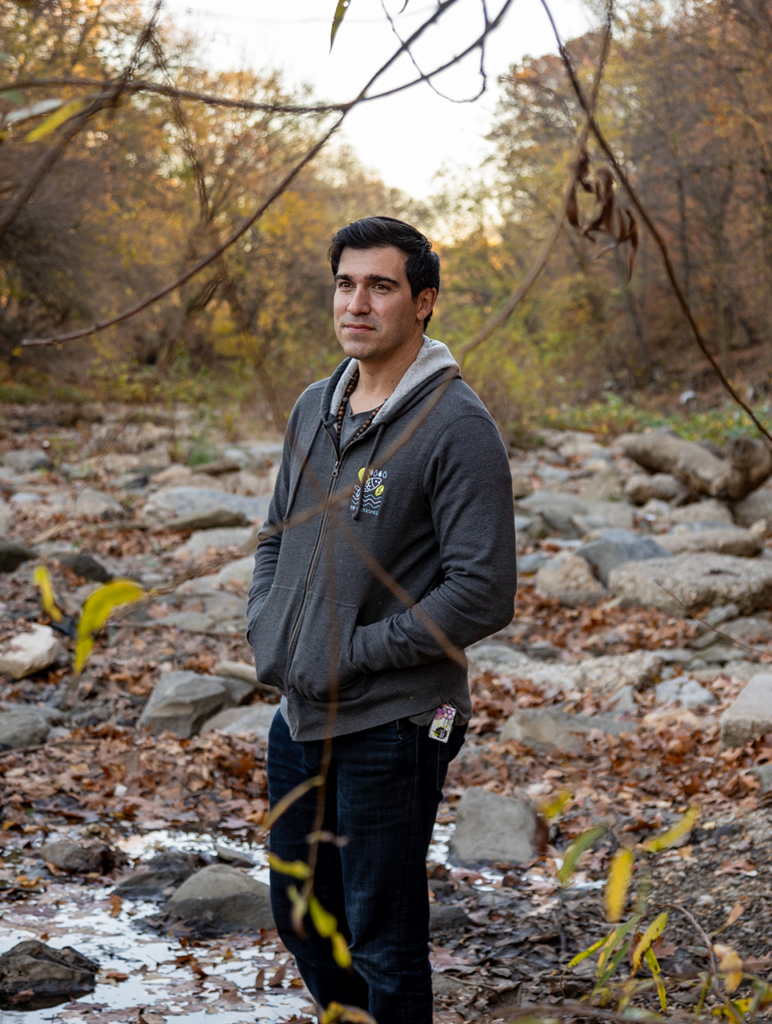

On the morning of September 13, 2023, James Aye, cofounder and co-CEO of the Youth Empowerment for Advancement Hangout (YEAH Philly), a Black-led nonprofit that provides critical services to teens and young adults, refused to leave a hearing when ordered to do so. An 18-year-old probationer, a YEAH Philly client and the subject of the hearing, had requested Aye’s presence.

Aye was arrested, spent a night in jail, and was charged with obstruction of justice, resisting arrest, disrupting meetings and defiant trespass. Prison was a possibility.

Aye’s stance reflects YEAH Philly’s drive to, per the organization’s mission statement, help the Philadelphians from ages 15 to 24 most at risk of getting caught up in violence — or already in its snares. “Too often, this is the young Black person who’s been kicked out of their home or out of their school without receiving quality services from the city,” says Kendra Van de Water, LSW, cofounder and co-CEO of YEAH Philly. Many of the group’s clients also have lost a loved one to violence, she says.

Within days of Aye’s arrest, State Representative Rick Krajewski and City Councilmembers Jamie Gauthier and Kendra Brooks issued a joint statement, citing Aye’s courtroom presence as “part of YEAH Philly’s transformative work in youth advocacy recognized by leaders across the Commonwealth.”

Last year, that work meant attending 1,002 hearings, giving legal guidance to 131 young people and helping 87 of them stay in the community instead of being incarcerated, says YEAH Philly’s 2023 annual report. The group also pushed for transparency in the juvenile legal system with an ad in bus stop kiosks in August 2023, a month before Aye’s arrest, asking, “Who’s watching juvenile judges?”

The joint statement also called YEAH Philly “champions of our community,” suggesting that the nonprofit’s unconventional approach to aiding young people yields benefits beyond the juvenile legal system.

YEAH Philly grew from Aye’s and Van de Water’s frustration with programs organized by schools, the government and other institutions whose many rules often lead young people to disengage. In 2019 Aye and Van de Water knocked on the doors of about 300 young West Philadelphians and surveyed them about their needs. The responses shaped free workshops Aye and Van de Water began giving at recreation centers, including the one in Cobbs Creek, on topics such as conflict resolution, stress management and sexual health. When word spread, the gatherings outgrew the sites. In 2021, the search for an adequate space led to a two-story house in West Philly, purchased after a crowdfunding campaign raised the required $200,000.

Youth, largely from West and Southwest Philly, can get a hot meal, a hot shower, tutoring, job and housing referrals, counseling, help with budgeting or opening a bank account and more, says Van de Water of the hangout, open 2 p.m. to 10 p.m., Monday through Friday. Young people may nap there but not spend the night. The hangout serves more than 500 clients per year, according to the annual report. YEAH Philly encourages them to take the two-day peer mediation and conflict resolution workshop, tailored specifically for the young Black clientele. Participants receive $150 upon completion.

We see a lot of harm and corruption … in our legal system, and oversight would mean some accountability.”

— Kendra Van de Water, YEAH Philly

The workshop advances YEAH Philly’s goal of helping young people reduce harm and avoid violence and extricate themselves from the juvenile legal system if they have become involved in it. “We’re advocating for every young person to have an independent counsel of their choice and independent oversight of the juvenile legal system,” Van de Water says. “We see a lot of harm and corruption … in our legal system, and oversight would mean some accountability.”

Aye and Van de Water also seek alternatives to detention. Incarceration further harms young people and is money ill spent, according to Van de Water. “It costs $220,000 per year per kid in Philadelphia’s Juvenile Justice Services Center,” she says. “At YEAH Philly, we spend $20,000 per kid per year and get far better results.”

In addition, YEAH Philly is working to change the electronic monitoring of youth and in-home detention. House arrest means that kids can’t leave the house at all, Van de Water says. That requirement often shuts the door on counseling, tutoring and participating in activities like sports, unless probation authorities approve them well in advance. Sometimes they don’t, Van de Water adds.

YEAH Philly also seeks more restorative justice programs and practices, such as one in which the person harmed and the young offender meet under certain conditions.

On the state level, YEAH Philly is working to stop the practice of charging young people as adults. “We don’t believe any kid should be in prison,” Van de Water says. The focus, she stresses, should be on rehabilitation and support.

Those efforts in Harrisburg dovetail with the nonprofit’s goal of increasing clients’ political savvy. A group of YEAH Philly staffers and participants visited the state capital several times in 2022 to urge legislators to back changes that would allow young people to request their birth certificate — needed for employment — at age 16 rather than 18. “We were in the voting room when they said ‘Aye!’ or ‘Nay!’” says Presley Barner, 18, a program participant and intern. The measure passed.

Activities like camping, travel and zip-lining further stretch clients’ outlook. “We visited Bar Harbor, Maine,” Barner says. “I ate lobster there. It was the bomb! People may give you money, but the best gift is experience.”

YEAH Philly’s innovations have borne fruit. While 17 clients were rearrested for violations or new charges, 21 young people were discharged from the legal system, 44 were placed in long-term paid training and 99 were trained in peer mediation and conflict resolution, among other accomplishments, according to the annual report.

In another heartening moment, YEAH Philly staff attended The Gault Center’s Youth Defender Leadership Summit in Denver. At the event, which champions justice for youth, they discussed the success of their Violent Crime Initiative’s intensive services for young people with representatives from other states and cities.

In addition, District Attorney Larry Krasner’s office withdrew the charges against Aye one year after his arrest because the case wasn’t moving forward, Van de Water says.

To achieve these outcomes, Aye and Van de Water often put in 12-hour days. Getting funding from private foundations, the government and donations takes time, Van de Water says. “Everyone wants to fund what’s popular at the moment, yet we’re always here doing what’s right for young people, not following a trend,” she says. YEAH Philly’s continuing efforts to invest in the community, spur change in the juvenile legal system and prepare young Philadelphians for empowerment and success are motivated not by buzzwords, hashtags or fads but by the needs — and goals — of the city’s youth.

“We cannot tell young people what to do,” Van de Water says. “We’ll continue to respect them as the experts about their own lives.”

To support YEAH Philly, visit yeahphilly.org and click “Donate.”