Hydrogen as an element is simple. Each atom has one electron and one proton. It’s first on the periodic table — the most abundant chemical substance in the universe. But hydrogen as a potential climate-friendly energy source is anything but simple. Hydrogen has long been used in dirty industries: cleaved from fossil fuels, it can be used to create fertilizers, petroleum and other chemical applications. Now, a rapidly growing number of private and public entities say hydrogen can instead be made into a clean fuel of the future, powering everything from homes to buses to airplanes.

And Philadelphia is poised to be a major testing ground for whether or not that’s true.

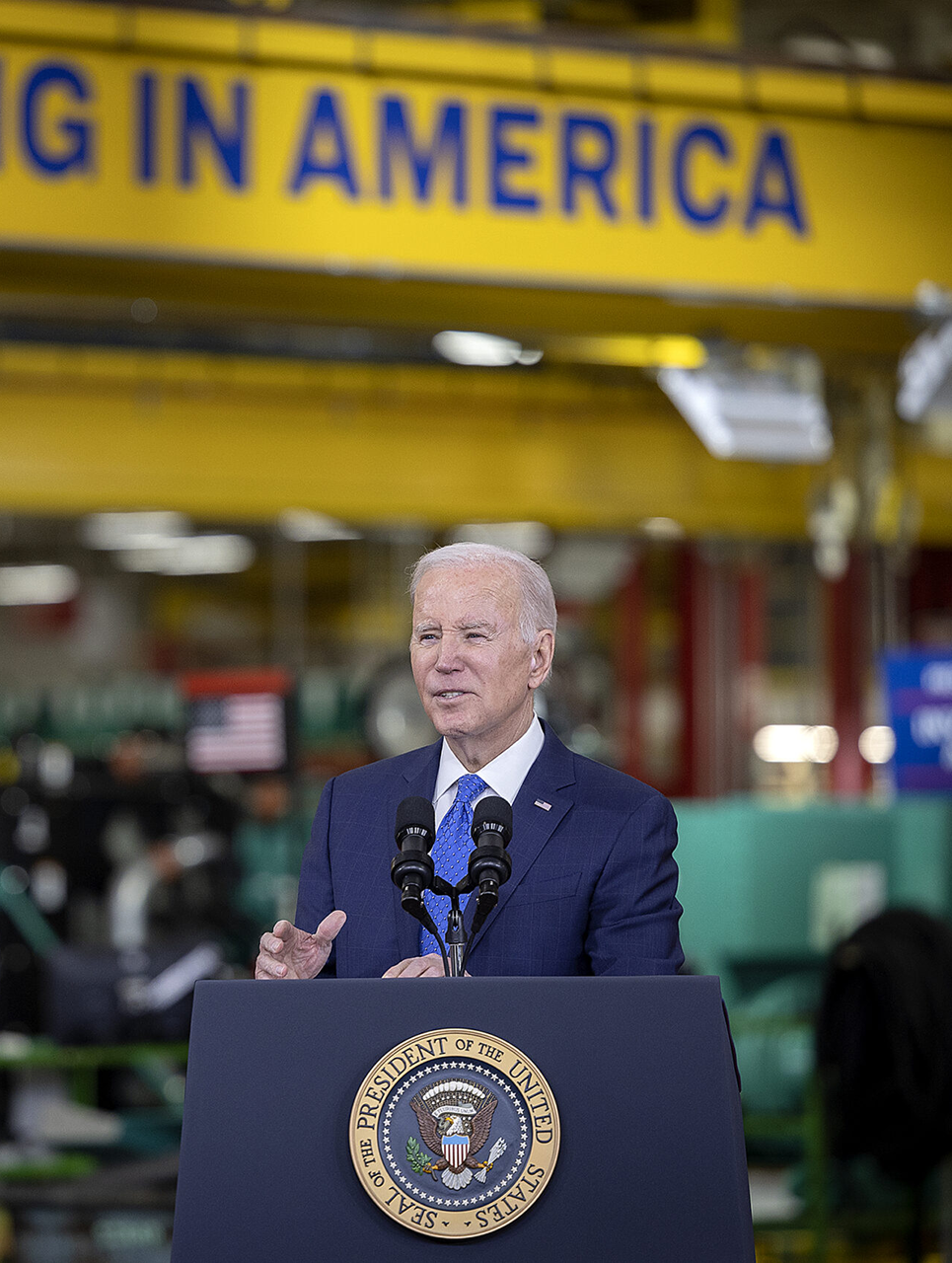

Last October, President Joe Biden visited the city to announce the Delaware Valley as one of seven likely recipients to share in an $8 billion dollar federal investment and become a “Mid-Atlantic Clean Hydrogen Hub” (MACH2). The only thing standing between the region and an initial $750 million award is a successful negotiation of terms in the months ahead. If the region receives the money, it would be used to help build out hydrogen production, storage and transportation facilities at more than a dozen potential sites spread across Southeastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware.

Biden’s October surprise was applauded by a bevy of local powerbrokers, many of whom had worked together on the region’s application. Politicians including then-Mayor Jim Kenney, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro and U.S. Senator Bob Casey all issued celebratory statements, as did labor leaders.

“The [hub] represents transformative investments in our city and commonwealth, creating thousands of family-sustaining jobs and tapping into our vast talent pool,” Kenney said at the time. “Over the next decade, we have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to see that our current energy workers are part of a just transition to the new energy economy.”

But others warn of a potential ruse.

Hydrogen fuel is neither inherently renewable nor inherently clean because you need other energy sources — either renewables or fossil fuels — to produce it.”

— David Masur, PennEnvironment

“Hydrogen fuel is neither inherently renewable nor inherently clean because you need other energy sources — either renewables or fossil fuels — to produce it,” David Masur, executive director of the nonprofit PennEnvironment, said upon the MACH2 announcement. “Federal, state and local officials should only support hydrogen energy projects that meet a set of basic, crucial criteria to ensure that they help reduce the nation’s carbon footprint, instead of potentially adding to it.”

A glance at MACH2 materials would indeed raise the eyebrows of any area environmentalist. The initiative’s website and presentations contain references to companies wrapped up in the fossil fuel industry, or with otherwise poor environmental track records: Enbridge, Monroe Energy, Air Liquide and DuPont. Potential storage or generation sites populate highly industrialized areas along the I-95 corridor, from the former Philadelphia Energy Solutions site in South Philadelphia to Marcus Hook, Delaware County, and into Delaware.

Yet some in the scientific and environmental communities also express interest in hydrogen as a low-or-no-carbon fuel of the future. Michael Mann, a renowned climate scientist and director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media, has opined that the promise of hydrogen fuel generated using renewable energy is “worth exploring.”

And Collin O’Mara, who is straddling worlds as chairman of the board for MACH2 and also CEO of the National Wildlife Foundation, says that Philly’s proposed hydrogen hub indeed promises to be climate-friendly. Speaking to the Sierra Club’s Delaware Chapter in November, O’Mara told members that by using renewables or low-carbon energy sources like nuclear energy to develop hydrogen, the MACH2 hub promises to be one of the greenest among those poised to receive federal dollars.

“Our hub came out as having the lowest emissions as any in the country, and also the most labor friendly,” O’Mara said.

The upsides of hydrogen

Using hydrogen as a source of power is nothing new.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, humans currently produce about 120 megatons of hydrogen annually, fulfilling about 3% of global energy demand. But present hydrogen production is almost entirely dirty from a carbon pollution perspective.

About 95% of hydrogen currently comes from natural gas, says the U.S. Department of Energy, through a process in which gases like methane are exposed to steam, hydrogen is extracted and climate-warming carbon dioxide is cast off as a byproduct. The extracted hydrogen is then primarily used to refine petroleum and produce fertilizers. The industry is dominated by major international gas and chemical companies such as Linde and Air Liquide.

But, proponents say, hydrogen has vast potential to leave its dirty ways behind. In most cases, a newer model looks something like this: wind, solar or potentially nuclear energy would power devices called electrolyzers that split hydrogen from water. Then, as hydrogen produces no carbon emissions, it can be distributed and used to power everything from industrial processes to cars, planes, ships and even power plants. All with essentially a zero-carbon cost.

Sweetening the deal, many see hydrogen as a useful tool to help address the peaks and valleys of renewable energy generation, similar to battery storage. When robust sunlight or air currents cause renewable energy generation to outstrip demand, excess energy could be used to instead create and store hydrogen, which can then be used as an energy source at any time for a variety of applications.

“If the 1990s were the decade of wind, the 2000s the decade of solar, and the 2010s the decade of batteries, the 2020s could launch us toward a next frontier of the energy transition: hydrogen,” the International Monetary Fund has declared.

Leaky plans

Despite its tantalizing potential, experts caution that for a host of reasons, hydrogen’s use as a beneficial, clean fuel still comes with a raft of uncertainties. At best, many experts say, its use will likely be limited to only certain sectors. At worst, it could be used as a cover for fossil fuel companies to continue polluting.

As hydrogen’s potential as a no- or low-carbon fuel begins to ramp up, along with potentially hundreds of billions of dollars in federal subsidies for its production, traditional gas companies have begun to enter the space and concerns about greenwashing have arisen. Those concerns have led to an effort to label hydrogen production methods by colors: “gray hydrogen” for traditional dirty methods, “green hydrogen” for renewable energy-based methods that generate no carbon emissions, and “pink hydrogen” created by electrolyzers powered by nuclear energy.

But muddying the waters further is also “blue hydrogen,” which uses processes similar to traditional methods but in which industry promises to “capture” the carbon byproduct of hydrogen production. Even more complicated are so-called “orange” and “white” hydrogen production methods, which involve extracting hydrogen from geologic formations using various techniques. Industry claims the methods have a lower carbon footprint, but some environmental advocates call that specious and say that some methods look a lot like fracking.

Even in the best-case scenario — creating hydrogen through 100% renewables — experts say the fuel will have its limitations. Wilson Ricks, a doctoral candidate and member of the Zero-Carbon Energy Systems Research and Optimization (ZERO) Lab at Princeton University, says that exactly which applications hydrogen will be used for is still uncertain as technologies are developed.

Key are not only questions of technical capability, but cost. Electrolyzers that produce hydrogen from water require copious amounts of energy to run. In many cases, it would make more sense to use renewable energy to power the grid directly instead of creating hydrogen. In wind and solar-rich states like Texas, it could make sense to use renewable abundance to generate hydrogen and power local industries. But the economics diminish the further hydrogen has to be transported, likely by pipe or ship.

“It really matters where you are and what the quality of the renewable resources are,” Ricks says.

For these reasons, many experts see the most potential for hydrogen not in powering homes and vehicles, but in industries like aviation, steel and cement production that are not served well by wind and solar. Mohamed Atouife, a Princeton doctoral student studying green hydrogen’s potential in heavy industry, says producing steel typically requires the use of coal-powered furnaces that create significant carbon emissions.

One potential option is to try to use carbon-capture techniques to cut pollution from steelmaking, but those technologies remain largely unproven and don’t solve the problems inherent with coal mining. Hydrogen, Atouife says, is the most advanced technological alternative.

“You have the hydrogen pathway, which can really get you down to about 90% emission reduction,” Atouife says.

But the further one steps away from the theoretics of hydrogen and toward its actual application, the more potential problems arise. One is the question of hydrogen leakage. As the smallest element in the universe, hydrogen is slippery and runs a high risk of leaking out of storage vessels or transportation modes like pipelines. That could become particularly problematic if companies try to cut corners by reusing pipelines that previously carried fossil fuels and were not designed for hydrogen.

And even small amounts of leakage would be self-defeating. A 2023 study by scientists at Norway’s CICERO Centre for Climate Research estimated that leaked hydrogen has a global warming effect around 12 times greater than carbon dioxide due to its amplifying effect on greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere. That means that even hydrogen created entirely by wind and solar energy could exacerbate the climate crisis should it leak out during production, shipment or storage.

There are also other pollution concerns. When hydrogen is combusted for certain applications, it can generate nitrogen oxides (NOx), harmful air pollutants that contribute to smog and are particularly problematic for the fenceline communities near industrial areas where many hydrogen operations will likely be located. Creating green hydrogen also requires copious amounts of water to be withdrawn from the environment. Pink hydrogen created by nuclear energy comes with all of the byproducts and downsides of that technology.

The economics and ecologics

Regardless of the pitfalls, hydrogen production appears primed for rapid growth across the globe, and quite possibly in the Delaware Valley.

Bridget van Dorsten, a senior research analyst studying hydrogen at the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, forecasts that global demand for hydrogen will increase two- to sixfold between now and 2050. And while green hydrogen makes up less than one percent of the total hydrogen market today, the firm anticipates it will account for more than 80% of hydrogen production by 2050.

But there is still much uncertainty about how it will all play out.

“Is it too early to say which demand sector is going to win out? Yes. It’s a really embryonic market,” van Dorsten says. “We don’t have a good feel for what the demand markets are going to be and where there is going to be a good willingness to pay.”

Enter the Biden administration, which has attempted to juice hydrogen production through offering economic incentives in its two landmark pieces of legislation, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Experts say the two somewhat work together. The Inflation Reduction Act offers tax incentives that provide about $3 of value for every kilogram of hydrogen produced. Ricks, of Princeton’s ZERO Lab, says that the incentive mostly closes a profit gap between gray and green hydrogen and could actually cover the entire cost of green hydrogen production as technological advances drive down costs. And while there was some question as to whether the tax incentives would potentially go toward the production of dirtier forms of hydrogen production, analysis by the ZERO lab of new Department of the Treasury rules indicates the administration is building in appropriate safeguards.

The effects of the tax credits could be huge: Ricks says that estimates of demand for the credits range into the hundreds of billions of dollars, and potentially as high as $500 billion “if the industry really takes off.”

But for that to happen, producers of hydrogen would have to be confident they could find buyers for all that product. With demand for green hydrogen currently extremely limited, that’s where the hydrogen hubs come in. With about $8 billion in potential funding from the infrastructure law in-hand, the Department of Energy has proposed seven different hydrogen hubs across the country, with MACH2 among them. Ricks says part of the idea is for each hub to test different technologies and develop working hydrogen economies — producers, transporters and users — that can then scale up as the technology and commerce progresses.

But area environmentalists like Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the environmental nonprofit Delaware Riverkeeper Network, are concerned about problems slipping through in the push for development. “We’re just getting up to speed on hydrogen,” Carluccio says. “But we have been concerned about it all along, because we’re concerned it [could] have a tremendous amount of environmental impacts and community impacts in the region.”

It’s not a way to attempt to decarbonize that’s efficient or acceptable. We really need to focus on direct use of renewables.”

— Tracy Carluccio, Delaware Riverkeeper Network

At this point, there appears to be no central clearinghouse for potential projects and regulatory processes related to MACH2 and thus no opportunities for the public to assemble and ask questions or air concerns as they would for a major gas pipeline project. There are whispers among area environmental groups of applications for developments potentially connected to the hub already popping up in townships across the region, leading to further concern that any problems wouldn’t be identified and addressed holistically until shovels were already in the ground.

Other proposed projects, like an Appalachian hub (ARCH2) centered around West Virginia and Western Pennsylvania, have also drawn criticism for their likely use of dirtier hydrogen production methods such as natural gas with carbon capture.

But Ricks says MACH2 might be one of the most enigmatic of all. The Delaware Valley’s energy market is dominated by natural gas, coal and nuclear. Due to its higher latitude and humid climate, wind and solar don’t provide as much juice as they do across the plains and sunbelt. Adding to the problem is the exit of Ørsted from the New Jersey off-shore wind market last year, casting further doubt about where renewable energy to create green hydrogen would even come from.

“The real challenge is going to be justifying the actual production of hydrogen in a region where the local clean energy resource base is not as high quality,” Ricks says. “The philosophy of MACH2 is, is there going to be some role for producing hydrogen even in places where it’s not physically optimal, because we think the alternative of transporting it is worse?”

Carluccio says the Riverkeeper Network remains deeply skeptical of the hub, and would prefer to see both attention and federal resources focused on the development of renewable technologies.

“It’s not a way to attempt to decarbonize that’s efficient or acceptable. We really need to focus on direct use of renewables,” Carluccio says. “Think of what we could do with $7 billion, and then billions more dollars of tax subsidies for renewables. Why aren’t we doing that?”