It was going to be transformational. A place for neighbors to shelter during extreme heat or cold. To receive relief and support after natural disasters. To learn about large forces like climate change and environmental justice and understand how they intersect in this corner of South Philly called Grays Ferry. The building would host teach-ins and green job training and provide a new home for Philly Thrive, the community organization instrumental in shutting down the Philadelphia Energy Solutions oil refinery that had been poisoning the neighborhood for more than a century.

The Grays Ferry Resilience Hub, as envisioned by neighborhood resident and Philly Thrive board president Sonya Sanders, was going to be a place where people could come to get their needs met, whether that was food assistance, home repairs or resources to help neighbors advocate for their rights.

The hub was to be a central operating location for all of Philly Thrive’s programming — a physical representation of their holistic approach to environmental justice.

The hub was to be a central operating location for all of Philly Thrive’s programming — a physical representation of their holistic approach to environmental justice. The staff already had its eyes on the perfect building.

Then, with the issuance of a single executive order, their plan went up in smoke.

$20 million lost, a year spent trying to regroup

When Philly Thrive and their partners at the Energy Coordinating Agency of Philadelphia (ECAP) and Habitat for Humanity applied for a Community Change Grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, they were told their resilience hub idea was one of the strongest proposals the agency had ever seen. The group was awarded $20 million to launch the hub, provide climate-safe home repairs and establish workforce training programs.

But that was in 2024, before President Donald Trump assumed office again and environmental justice became one term on a list of hundreds for which grants and programs could get flagged as wasteful spending and subsequently terminated.

Almost immediately after the new administration took office, Philly Thrive co-managing director Alexa Ross says, the organization found its access to grant funds was frozen. Advisors told staff to get started on the work anyway.

“We were being told from the start in January, both by ECAP and by the technical assistance that was being provided to groups, that ‘it’s very important — so that they can’t terminate your grant — that you move forward on the work,’” says Ross.

Ross and her team began what work they could, paying out of the organization’s operating funds, unsure when they could secure reimbursement. According to Ross, a May court injunction ordered the EPA to reinstate grantees’ access to the reimbursement portal, but a week later, the agency sent a formal termination letter, shutting off access to any money not already paid out.

“That window closed right in front of our faces to get back what was, at that point, nearly $100,000,” Ross says.

The termination rocked the organization, forcing the halt of its active programming and the layoff of all but Ross and two other employees, who are paid for just 16 hours a week but work many more to keep the organization afloat. They have had to pivot to emergency fundraising to try to fill the financial gap. The building they’d hoped to buy was sold to someone else.

“Everything was based on the federal grant coming,” says Sanders. “It would have changed our lives.”

Finding strength in local networks

Philly Thrive may be among the hardest-hit organizations in the Philadelphia area, but it is far from the only one. Public Environmental Data Partners, a volunteer group dedicated to preserving federal data, estimates that cuts to the EPA’s environmental justice grants have cost Philadelphia County more than $50 million in direct and indirect economic impacts. Organizations such as the Overbrook Environmental Education Center and Bartram’s Garden, projects such as the Eastwick Flood Resilience strategy, and research groups at most Philadelphia-area universities have lost federal grants.

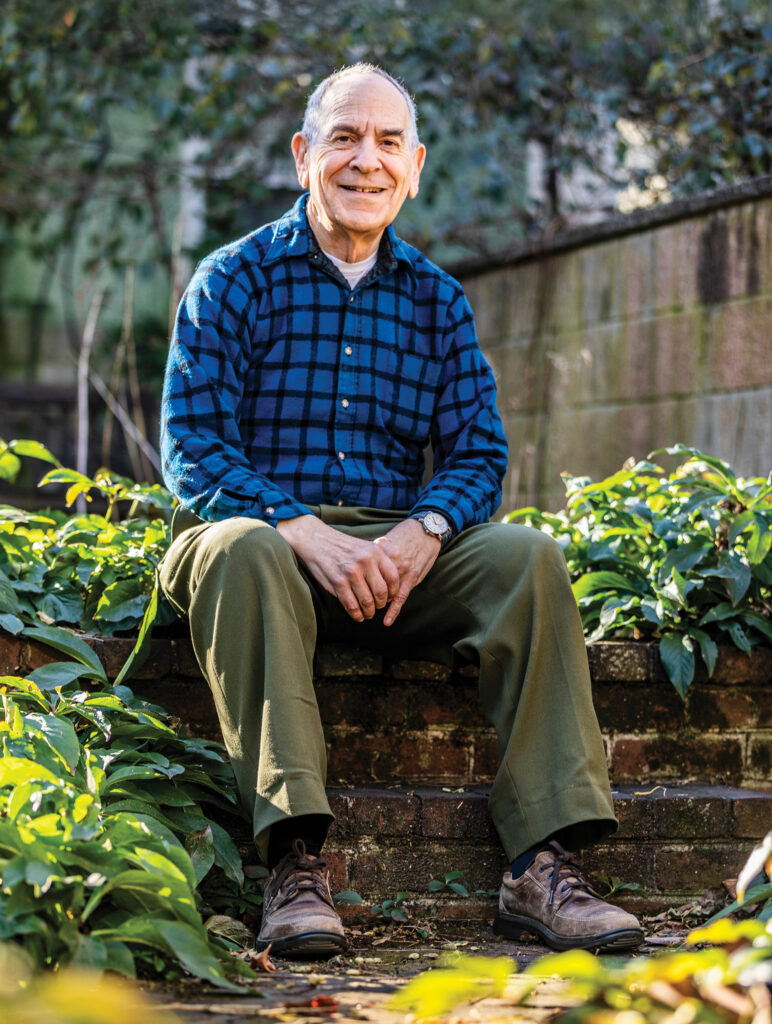

“Folks are now trying to figure out what next steps look like and what learning opportunities came out of it,” says Jerome Shabazz, who heads the Overbrook Center. “Some folks are thinking about how they have to have enhanced community engagement. Others are thinking about how to model different aspects of environmental work that is now de-emphasized federally. And some are getting very specific in terms of how to create new language to explain what it is that they’re doing, taking out those terminologies that have been disfavored.”

Before the cuts, Overbrook was designated as a local “hub organization” under the EPA’s Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers (TCTAC) program. The program provided tools and advice to support environmental justice organizations in the complicated process of applying for grants. Through TCTAC, Overbrook was part of a larger network of organizations across the Mid-Atlantic that exchanged knowledge and helped each other troubleshoot similar challenges. In turn, Overbrook played the support role for smaller environmental justice organizations around Philadelphia. The TCTAC program was cancelled in February 2025, and that regional connection was severed with it. But Shabazz says Overbrook was lucky to maintain some ability to continue acting as a local resource hub, thanks to other funding sources.

We still haven’t met the goal, but we are definitely inspired by all of the support that we’ve gotten from all of the different organizations, and even the everyday people that [are] part of the community.”

— Shawmar Pitts

“We want to be able to see ourselves as a partner to this work and whoever needs that help,” says Shabazz.

As federal funding becomes less reliable and even hostile to the work of environmental justice, Shabazz sees an opportunity for community groups, researchers and city leaders to enhance cross-organizational collaboration. It’s that solidarity and resource sharing within Philadelphia’s environmental justice community that has touched co-managing director of Philly Thrive Shawmar Pitts most during this moment of turmoil. When the organization launched its fundraiser, it was largely other local organizations that stepped up. As of December, Philly Thrive had managed to raise about 75% of its fundraising goal.

“They’ve been the ones that kept us here alive,” Pitts says. “We still haven’t met the goal, but we are definitely inspired by all of the support that we’ve gotten from all of the different organizations, and even the everyday people that [are] part of the community.”

Beyond the money

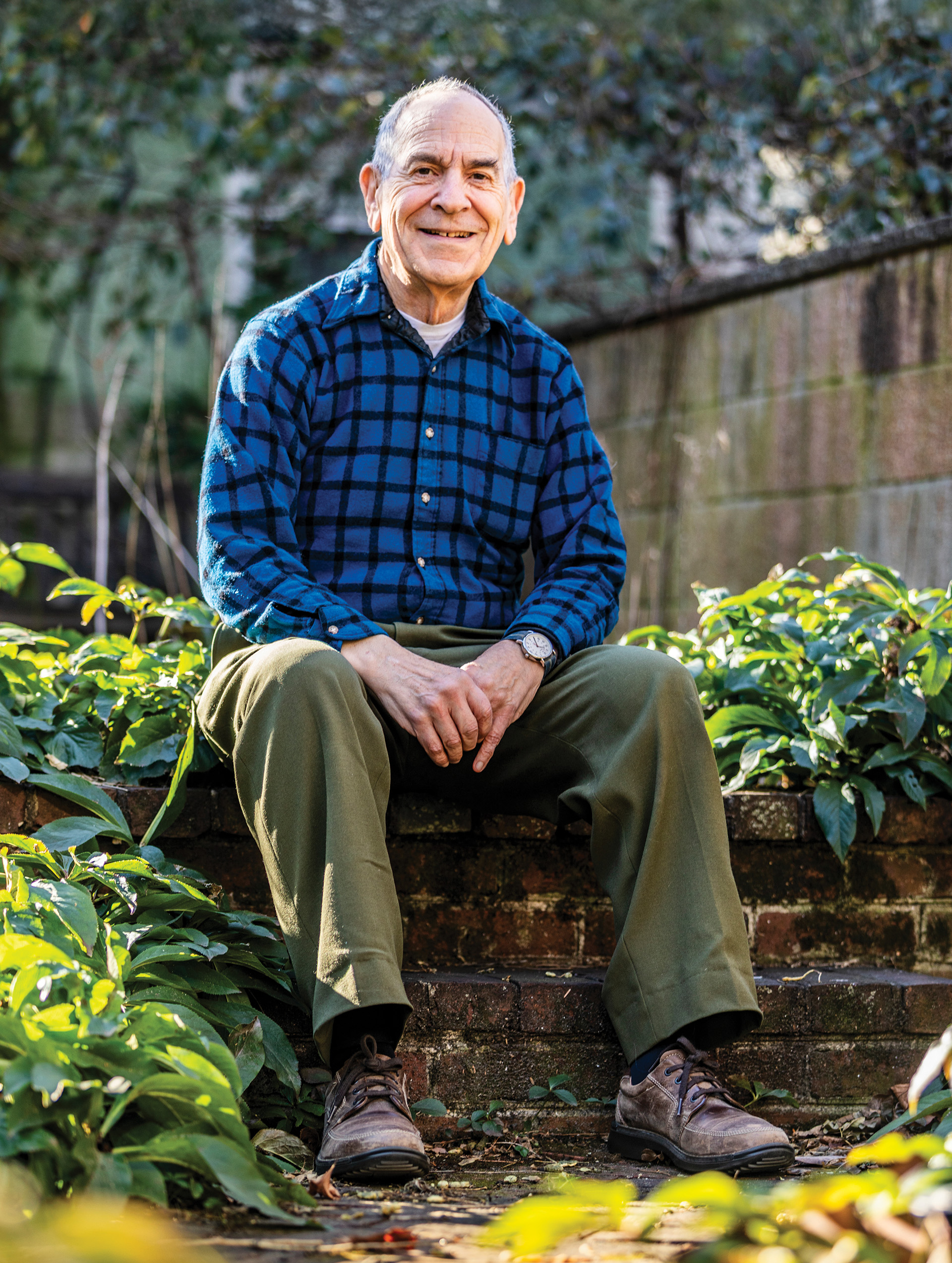

In addition to the money lost, the federal cuts will create cascading effects that place communities at risk in the long term, according to vice provost and executive director of The Environmental Collaboratory at Drexel University Mathy Stanislaus.

“You have direct resources that are not available,” he says. “But then you also have [the loss of] the science, data and enforcement that are crucially necessary to protect a community.”

Data loss, particularly related to environmental hazards, Stanislaus says, will have major consequences. Federal agencies have scrubbed their websites of many of the same terms that grants are being flagged for, including “climate science” and “environmental quality.” The Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (EJScreen), a federal portal that hosted data about environmental burdens like air and water pollutants, as well as demographic indicators including income, race and English language proficiency, has been taken down.

“As you pull back the data, communities will fail to understand and invest in the prevention and preparedness to prevent death, injury, damage to homes, damage to the economic conditions of neighborhoods,” says Stanislaus.

Publicly funded information is how Pitts first learned about climate change. He says he spent his childhood watching documentaries on WHYY-TV 12, Philadelphia’s public broadcasting station, about sea-level rise. Years later, when he encountered Ross speaking on behalf of Philly Thrive in Stinger Square Park about the injustice of the oil refinery’s placement and the abnormality of cancer and asthma rates in the neighborhood, he was able to connect the organization’s mission to a bigger environmental picture. He hoped that the Grays Ferry Resilience Hub would become a place where all neighbors could experience that connection for themselves.

“It would give everyone the opportunity to have that awakening of environmental justice, climate justice, and how to reverse climate change. [It would] give people the opportunity to understand what’s going on and get that information,” says Pitts.

Without federal support, communities will have to find workarounds to access the same information that was, until months ago, freely accessible. Public Environmental Data Partners has preserved a copy of the EJScreen website, as well as dozens of federal climate and environmental databases, for public access. Without funding to continue underlying research, however, these archived versions will slowly fall out of date.

“It just makes it a lot harder to do this work,” says Temple University professor Christina Rosan. Rosan had worked with Clean Air Council on a federally-funded planning grant to combine locally collected air quality data with government datasets in a tool that communities could use to identify local environmental justice concerns. Planning grants are intended to fund the prep work for larger, longer-term projects, but given the cancellation of the EPA’s environmental justice programs, Rosan says, there’s no longer a federal avenue to build out that project.

“I don’t see how it helps make people healthier and safer not to know about what’s in their neighborhoods,” says Rosan.

Shabazz hopes that communities themselves might be able to fill in data gaps. He uses the example of environmental “report cards” that could help communities understand risks like extreme heat and air pollution at a hyperlocal level.

“If we don’t have the resources to do that big thing, we should do it where we are,” says Shabazz.

Surviving for the community

For Philly Thrive, co-managing director Ross says it could take some time before the organization is able to find its new path forward. Meanwhile, the repercussions of the lost grant continue to echo. Though other grant recipients have joined in active class action lawsuits to challenge the termination, ECAP decided to formally close out the resilience hub grant at the end of 2025, by which point the federal government owed Philly Thrive close to $300,ooo. The closeout process requires all recipients to compile and submit final reports and provide any supplemental documentation on request. Philly Thrive could be accountable to the government for months to come, despite never receiving a single federal dollar.

But through the exhaustion, grief and complications, Ross says the organization is still finding new ways to get its work done, because the needs of Grays Ferry residents have yet to be met.

“Folks have not gotten any type of justice, and that keeps us at Philly Thrive up at night and showing up every day, even despite how tough this year has been,” says Ross.

Philly Thrive’s vision for justice still includes the resilience hub, but staff are looking at a much longer timeline to realize it. The organization is pursuing a grant from the William Penn Foundation to help it survey the community and isolate the most pressing needs, something Ross says it would have liked to do before applying for the Community Change Grant. She views this redirection as an opportunity.

“We can now work with the community to polish exactly how the hub functions, what services are most important to offer, and then when we have more of the community interested, excited, committed for the resilience hub vision, then we’ll be able to pursue the funding for it,” says Ross.

Philly Thrive is also continuing to engage in City housing policy, advocating for home repair and housing support for low-income residents across the city. Since the shutdown of the refinery, Sanders says neighbors have felt the pressures of gentrification accelerate. The redevelopment of the refinery land into a warehouse district has opened the area to new business interests, and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has broken ground on and plans to finish building a parking garage in the neighborhood this fall. Long-term residents, who suffered the health impacts of the refinery for decades, may yet be priced out of the neighborhood while others enjoy the benefits of its closure. This is not an outcome that Philly Thrive will accept without a fight.

“We want to be treated fairly. We want good homes too. You know that our lives do matter. Our health matters,” says Sanders.

So despite the setbacks of a tumultuous year, Pitts says the organization will, as ever, keep pushing for justice.

“We’re holding on and trying to survive,” says Pitts. “We want to be resilient, and we want to just weather the storm, because we know that good times will come again.”

—

Correction: In a previous version of this story, Philly Thrive’s total project expenditure was misreported and has since been corrected. Additionally, it incorrectly stated the number of hours that the remaining Philly Thrive employees are paid for per week, which is 16.

This article captures the deep frustration that many of us working in the nonprofit and community development sector continue to face as a result of abrupt and destabilizing federal funding decisions.

For ECA, the loss was not abstract. Alongside Philly Thrive’s leadership, including my longtime colleague and friend Shawmar Pitts, we envisioned the Grays Ferry Resilience Hub as a place where housing stability, workforce opportunity, and environmental justice could reinforce one another. ECA planned to replicate our highly successful Green Careers Training Center within the hub, while it also served as Philly Thrive’s headquarters and a true community anchor. Nearly 200 low- to moderate-income homes were slated for rehabilitation, weatherization, solar installation, and preparation for building decarbonization—investments especially critical in a community that has carried disproportionate environmental and health burdens for decades.

ECA’s Green Careers Training Center has a proven track record of connecting individuals who are unemployed or under-employed—including returning citizens and other justice-impacted individuals—to family-sustaining wages through industry-recognized training and certification in energy efficiency, weatherization, HVAC, and heat pump installation. For many participants facing significant structural barriers to employment, this pathway represents not just job training, but a second chance to build stability and contribute meaningfully to their communities.

While the termination of this project represents a significant setback, it also highlights the role that strong local leadership and place-based investment play in sustaining this work. Philadelphia has no shortage of institutions committed to equity, workforce development, and healthy communities. ECA remains ready to work with partners who understand that durable progress requires long-term commitment, trusted community relationships, and the willingness to invest where the need—and the opportunity for impact—is greatest.