Will you find yourself alone again for Valentine’s Day? It can be hard to find the right someone, but you’re not alone. Female oriental cockroaches can also have a hard time finding a mate. But when one gives up on finding a male to settle down with, she moves on to plan B: The female oriental cockroach can reproduce all on her own through the ultimate act of self-love, laying a clutch of eggs that hatch out as her clones.

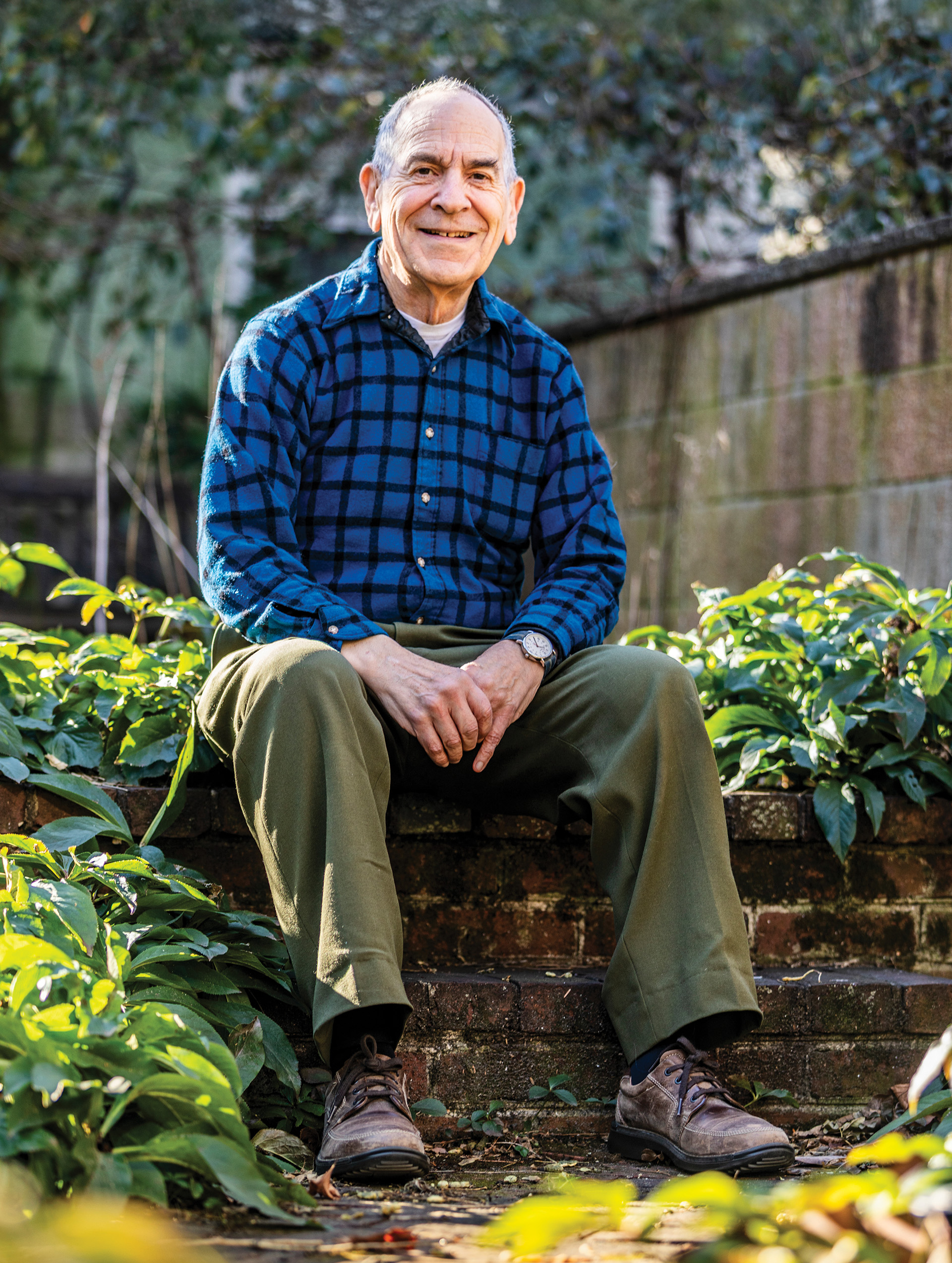

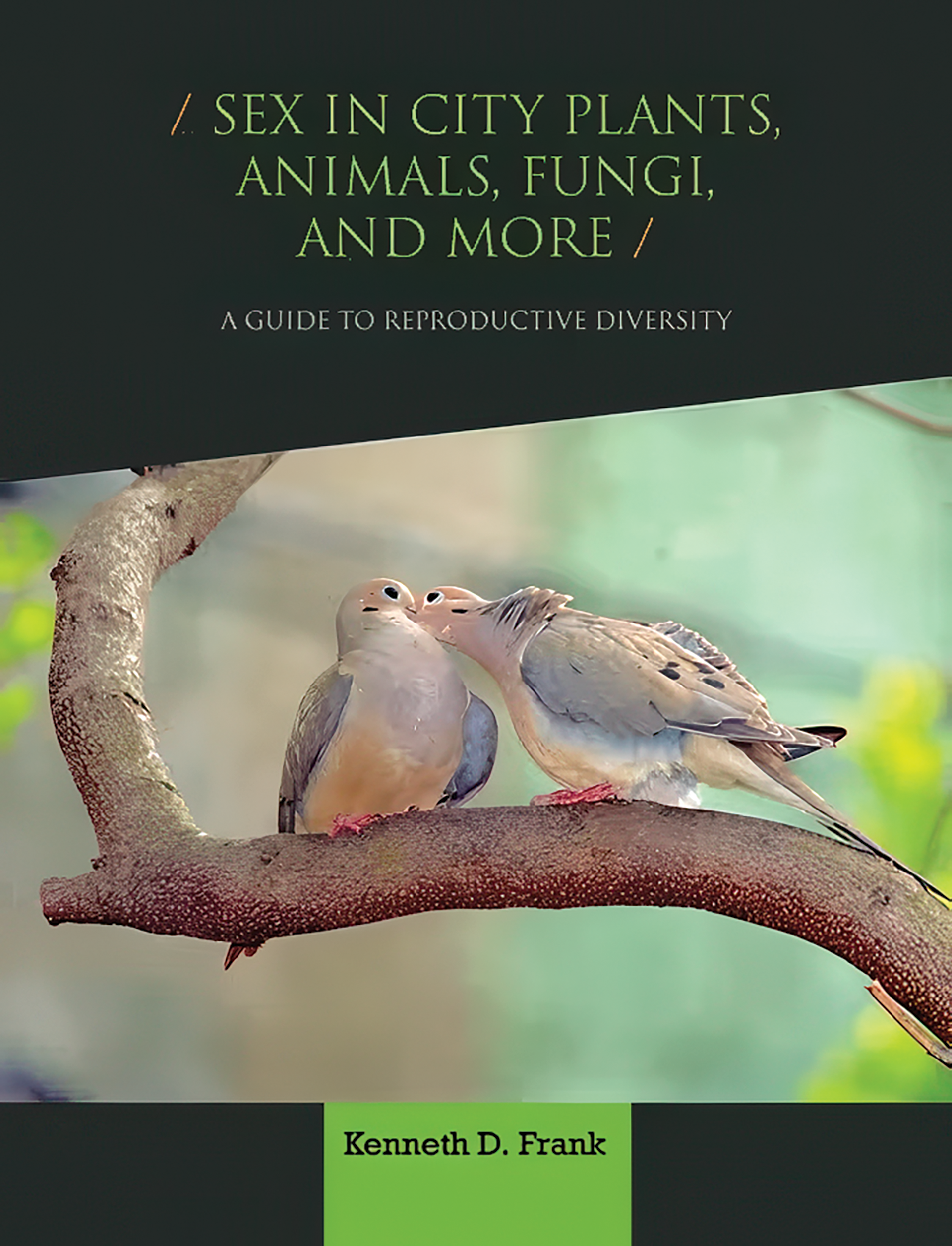

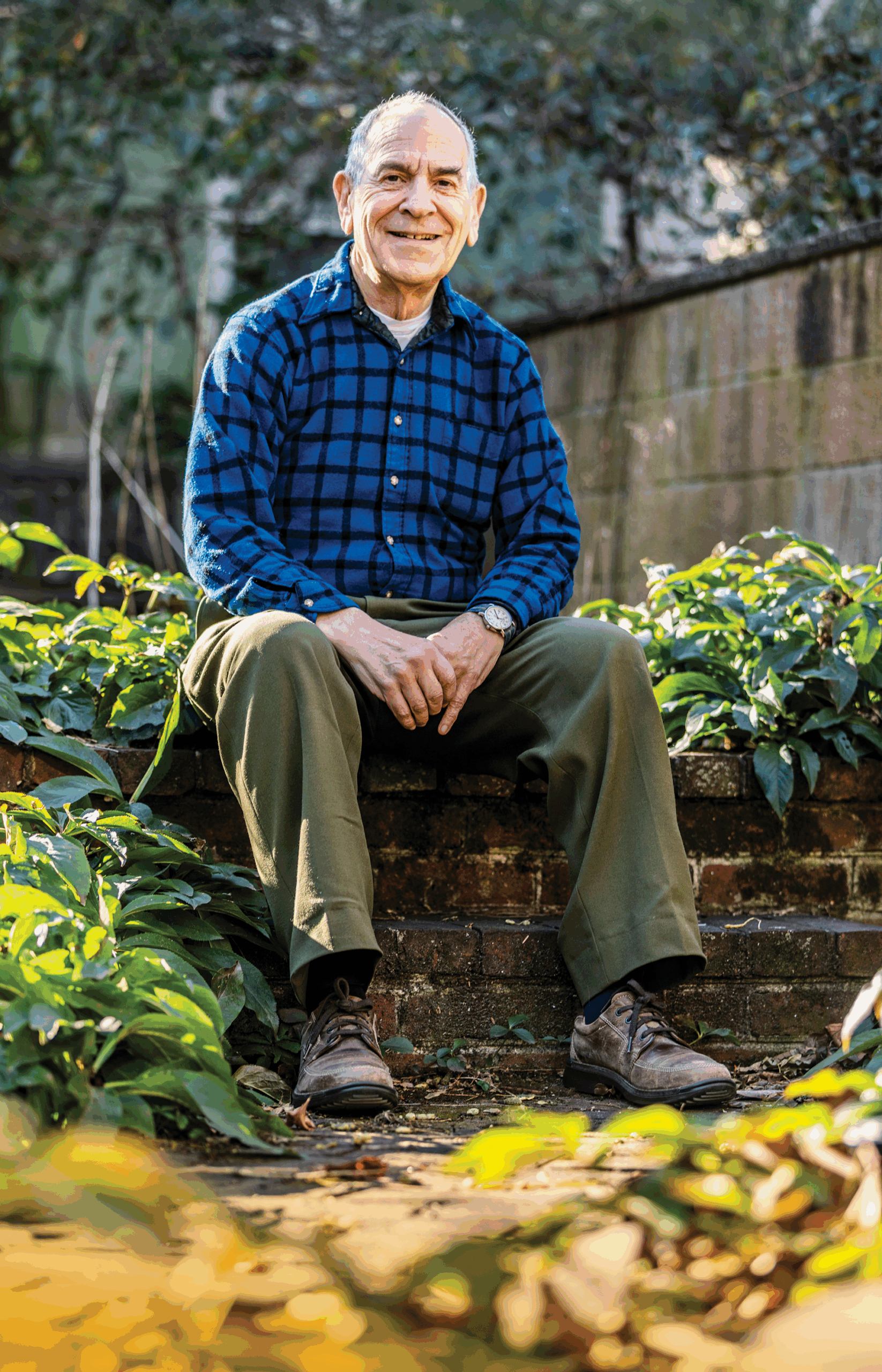

The story of the lonesome cockroach is just one of dozens profiled in Kenneth D. Frank’s “Sex in City Plants, Animals, Fungi, and More: A Guide to Reproductive Diversity,” the second work by the author of “The Ecology of Center City, Philadelphia.” Frank, a naturalist and retired physician who lives in the Fitler Square neighborhood, has long been fascinated by mosses and other diminutive plants that grow between the bricks of his sidewalk. He says the idea for the book came from his study of primitive plants called liverworts. “They’re so tiny, and some require both sexes to produce spores. And you wonder how they get together.” Beyond the natural limitations faced by immobile plants, Frank realized the urban landscape erects other barriers: buildings, roads and fragmented habitats. “It came to me that it would be fun to look at specific organisms and probe into how they do it.”

In biology, sexual reproduction refers to two organisms combining their genomes to produce offspring, whether they are in close physical contact or far apart. But plenty of plants (and some animals, such as your lonely cockroach housemate) can reproduce asexually — in other words, without mixing genes with a partner.

And some make it even more complicated. Male umbrella liverworts produce sperm on star-shaped platforms. They wait for rain to wash the wee swimmers over to a waiting female’s umbrella-shaped reproductive structure, where they merge with her ova. Those fertilized ova develop into tiny, dangling offspring that themselves produce spores. Those spores can be blown or washed away to eventually grow into new males and females. Frank thinks that one reason liverworts thrive underfoot is that sidewalk cracks help channel water, and thus sperm, from males to females. But even if sex doesn’t do it for the family-minded liverwort, “it has a backup system,” Frank says. A male or female liverwort can asexually produce tiny copies all on its own.

Female bedbugs might wish they had that option. You probably don’t need another reason to loathe the little bloodsuckers, but they practice what biologists call traumatic insemination. The male bedbug uses his sharp reproductive organ to pierce his partner’s abdomen and inject his sperm.

That’s not the only form of insect reproduction better suited for Halloween than for Valentine’s Day. Praying mantis females famously enjoy having males for dinner, though it turns out most of the hopeful guests don’t manage to get lucky before they get profoundly unlucky.

The male mantis would tell you (if his head hadn’t just been bitten off) that love can make a fool of anyone. This is perhaps most tragically true for males of our common eastern firefly. The male beetle flashes in a species-specific pattern as he flies above a field, hoping for an answer from an eager female waiting in the grass below. But some of those signals come from females of lightning bugs in the genus Photuris. These femme fatales have evolved to imitate the females of other firefly species so that when the duped suitor lands, the Photuris gals can eat him while they wait for one of their own males to fly by.

For true romance, look to the gray garden slug. When one amorous slug encounters another, they begin to dance. Slowly they circle on a bed of mucus as they get to know each other. The circle shrinks, the slugs grow closer and, finally, they touch, now rushing (albeit at slug speed) to embrace. Slugs are hermaphrodites, with male and female sex organs, and both partners can lay eggs after their slimy rendezvous.

Having all the equipment really opens the field of options for romantic slugs, but some mushrooms (or rather, the fungi that produce mushrooms) take it to the opposite extreme to ensure compatibility. These fungi mostly consist of masses of threadlike tendrils called hyphae that digest wood or other dead plant matter in the soil. When the tip of a hypha contacts one from a different member of the same species, the two can mix genomes and produce mushrooms, which then disperse spores. Fungi of the same “mating type” are reproductively incompatible, but luckily, there are so many mating types that the odds of encountering a suitable partner are extremely high. The common inky caps you see sprouting out of garden mulch have 143 such mating types.

Although many organisms have options, some find themselves limited by human choices. The threadstalk speedwell requires cross-pollination to produce seeds. The small plants can grow from fragments, whether intentionally divided by a gardener or scattered by a spinning lawnmower blade. It turns out that the plants originally exported from threadstalk speedwell’s native range in Türkiye and Georgia are clones, meaning that the pretty lavender flowers in Philly lawns are reproductively futile, unable to be fertilized. “How sad,” Frank says. “They’re doomed to celibacy.”