The Fairmount Park Conservancy, Philadelphia’s largest parks-focused nonprofit, has tread perilous ground over the past several years as it leads one of the largest open space transformations in the city’s recent history: a $250 million overhaul of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) Park in South Philadelphia. The conservancy has caught flak from some community and advocacy groups that are critical of elements of the plan. As reported in Grid #187, it is just the latest chapter in a long history of controversy over public park management in Philadelphia dating back to colonial times.

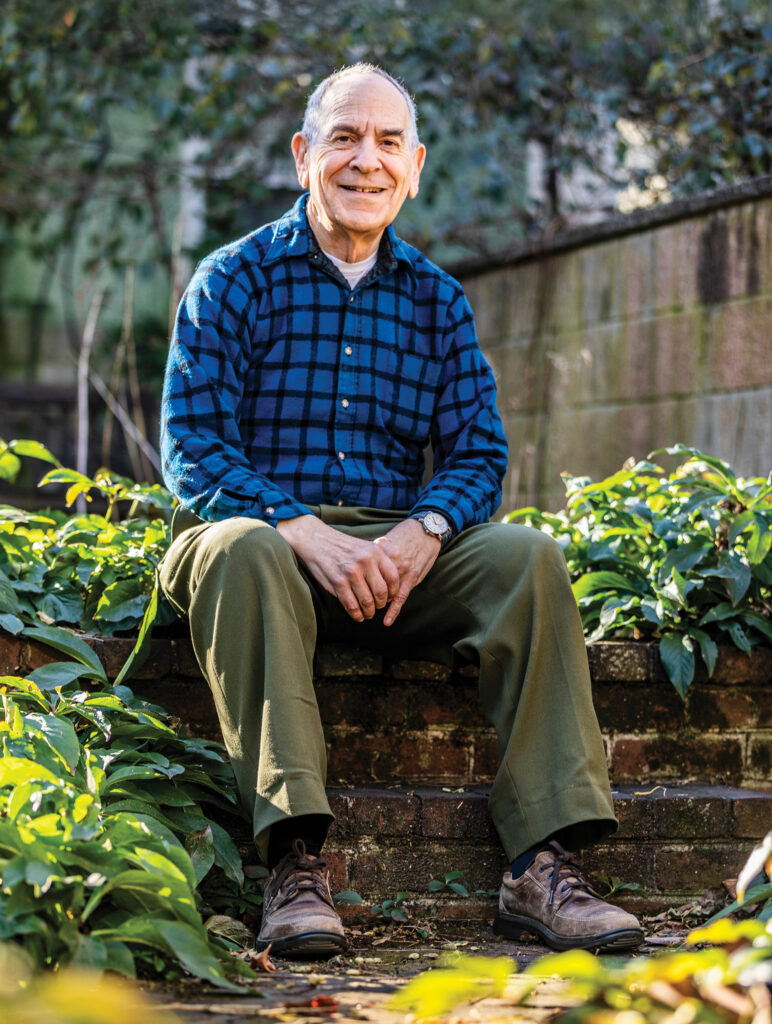

Despite these circumstances, Anthony Sorrentino, who became chief executive officer of the conservancy in October, is taking a decidedly optimistic — and open — approach to the job. Even before his first day, Sorrentino was waxing poetic and engaging in conversation about Philadelphia’s park system in a LinkedIn post. During an interview with Grid at the conservancy’s West Fairmount Park offices in November 2025, Sorrentino opened with an offer to “call me Tony” and said he planned to serve as a “happy warrior” for Philadelphia’s parks, boosting not only their physical quality but their profile in civic life.

“The conservancy is 28, going on 29 years of age, and has been going through its own growth spurts all that time, and I think it’s matured into an organization that’s kind of ready to be more than one or two things,” Sorrentino said, noting that it has traditionally served in a fundraising capacity. “There’s a moment for greater, lower-‘a’ advocacy. That might be the next level of maturity for the organization.”

Elaborating on what that advocacy could look like, Sorrentino pointed to the Park Friends Network, an umbrella group organized by the conservancy that includes approximately 140 nonprofits of various sizes supporting the city’s constellation of parks and playgrounds.

Sorrentino is working in the parks space for the first time. An urban planner by training, he spent most of his career at the University of Pennsylvania, working in the university’s executive offices as a sort of “glue guy,” with a portfolio that included liaising with both local and business communities, overseeing public affairs and determining urban policy.

To orient himself, Sorrentino spent several Saturdays in the fall visiting with about a dozen Park Friends groups during Love Your Park Week and getting his hands dirty alongside the other volunteers across the city. He found that the “motivations” of volunteers were the same no matter the size of the park and saw the possibilities of what could be.

“People are interested in their little corner of the world and seeing what they can do to make it better,” Sorrentino said. “Honest to God, if we built up those 140 Park Friends groups to be the most robust, self-sustaining groups they could be, then the advocacy [for improving park spaces] happens very organically at that point.”

Of course, that’s easier said than done. In addition to coordinating with more than 100 park groups, Sorrentino will have to navigate relationships with City officials — biweekly meetings with Philadelphia Parks Commissioner Susan Slawson are now a calendar staple — along with private donors and other powerful stakeholders who don’t always agree on what’s best for Philadelphia’s parks. Inequality in the parks system remains a concern, and some advocates believe that’s driven in part by philanthropic interests holding too much decision-making power.

In my 25 to 30 years doing urban work in Philadelphia, I’ve never seen a project that delivered everything everyone wanted all of the time. And you have to tolerate that.”

— Anthony Sorrentino

Sorrentino has an answer for how he’d handle that:

“I think if somebody is coming to the table and saying, ‘Here is a large amount of money, I want you to do what I want to do,’” Sorrentino offers, “we’d probably say, ‘Thank you so much for your interest and passion; tell me more about why you’re interested in it, why you’re passionate, and tell us about what your strategic priorities are,’ and see if there’s a way to reconcile those things.”

But he also says that it’s impossible to please everyone all the time. He believes the planning process that went into the FDR Park overhaul was “high quality” and reflected public input. But that doesn’t mean that people will see specific things exactly as they asked for, which he thinks is the source of strife. So even as he takes an optimist’s approach to the work, the example serves as a reminder of what happens when one’s intentions — even if good — enter the arena of public opinion.

“I think you can’t overcommunicate,” Sorrentino says. “But at the same time, you have to draw a line at some point. In my 25 to 30 years doing urban work in Philadelphia, I’ve never seen a project that delivered everything everyone wanted all of the time. And you have to tolerate that.”

Kyle, thanks for covering this important topic and leadership perspective and challenges. Kudos to Mr. Anthony for having a inclusive, patient, and pragmatic approach towards improving QoL for Philadelphians.