On the first warm Saturday of the year, Taylor Bakeman organized a seed packing event to restock The Discovery Center’s new native seed library. Just a few weeks after opening, its seed supply was already running low. A dozen volunteers spent the day counting and sifting tiny seeds of New York ironweed, anise hyssop and more than 20 other species into small manila paper envelopes, just the right size to fit into the drawers of a library card catalog.

Bakeman, 28, a volunteer at The Discovery Center and a user of seed libraries throughout her upbringing in Arizona, brought the idea for a seed library to The Discovery Center during her Pennsylvania Master Naturalist training. She came up with the project to reduce barriers to growing native plants, after experiencing difficulties finding native seeds and plants at an affordable price.

“Being familiar with using a seed library and wanting to advance the accessibility of native seeds, I thought it was the perfect thing to have, especially in a place like The Discovery Center,” says Bakeman.

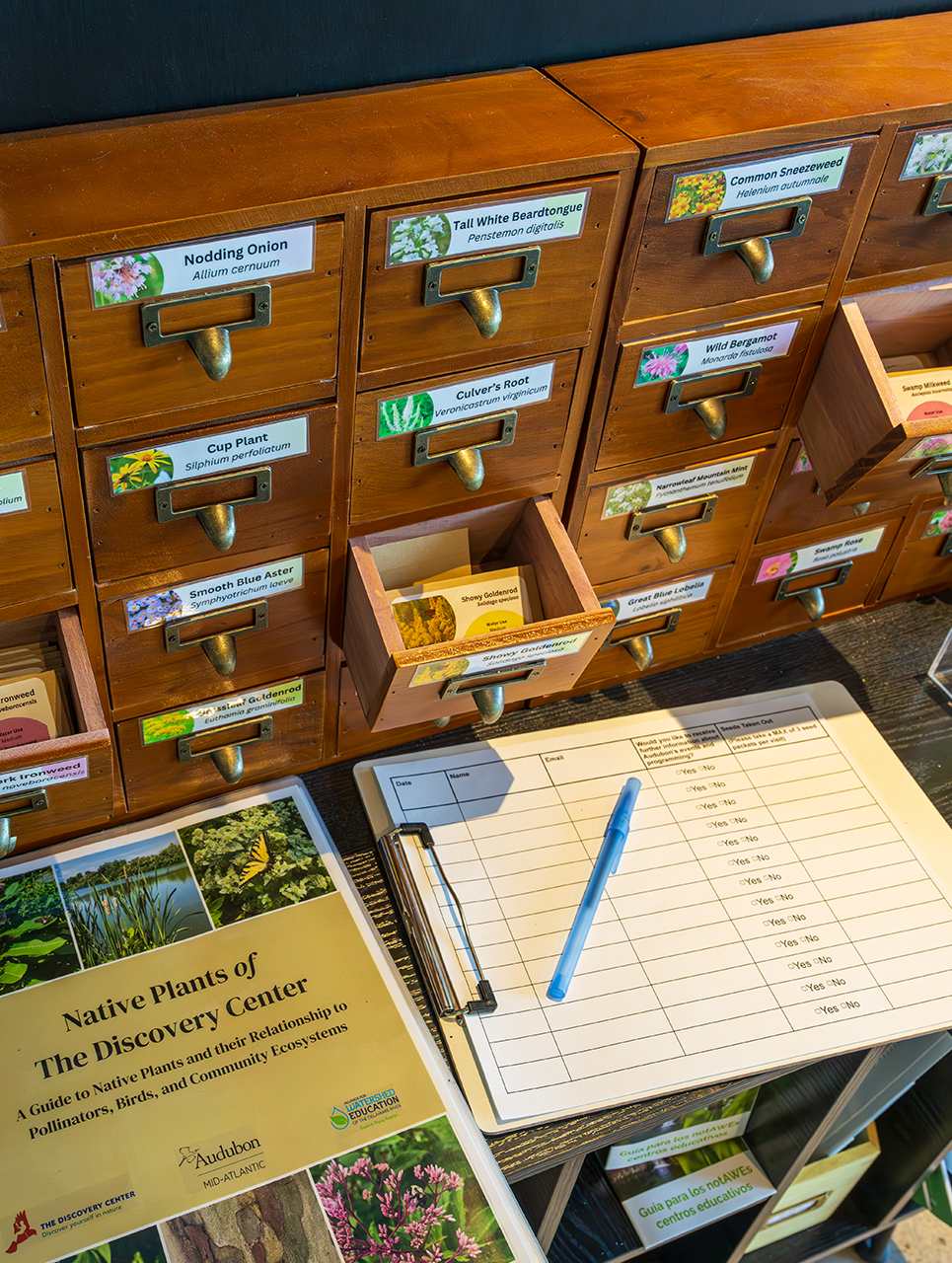

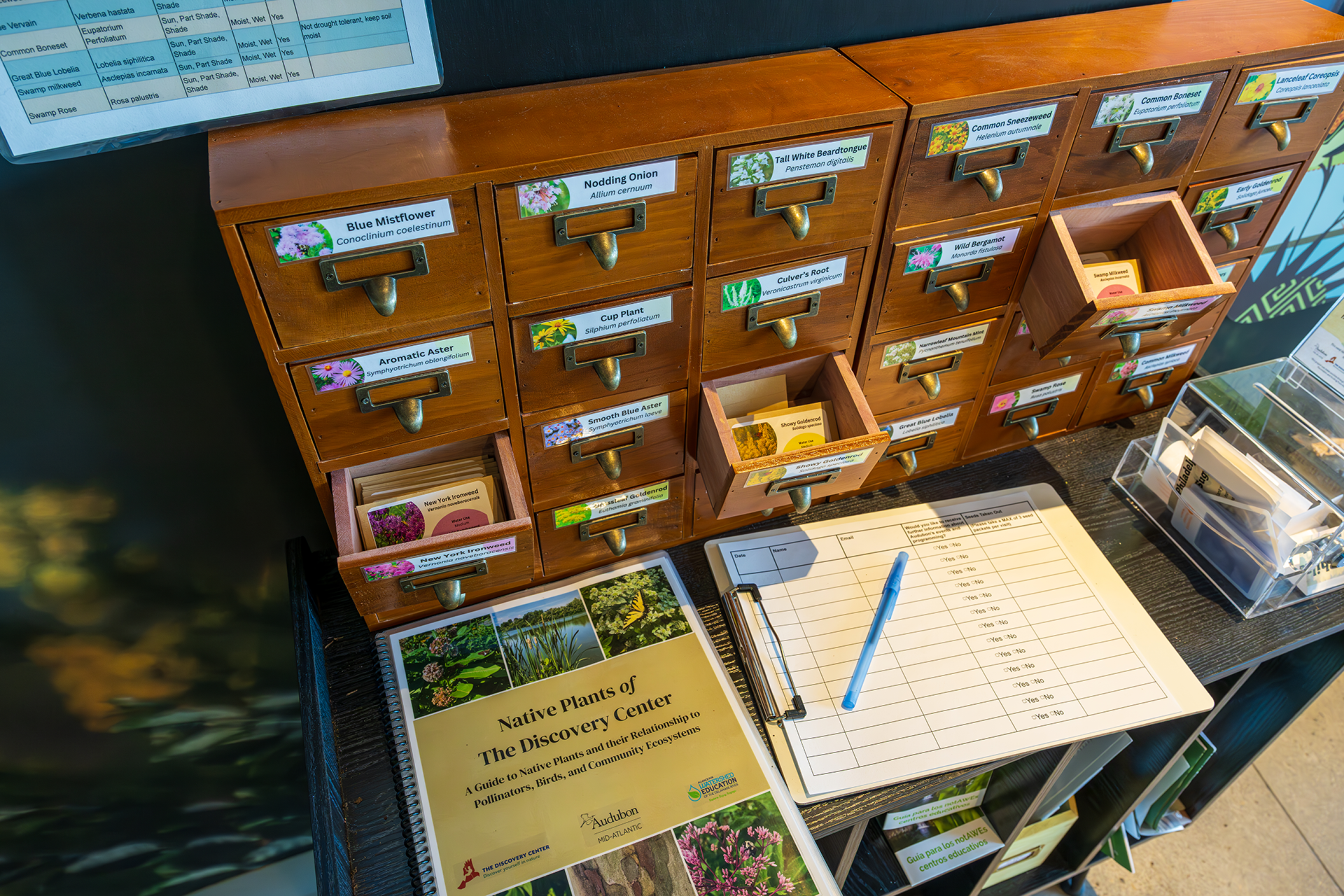

The Discovery Center, an environmental center run by Audubon Mid-Atlantic and Outward Bound in Strawberry Mansion, officially opened its seed library to the public on February 1. In a windowed corner of the main building, a pair of card catalogs — pine cabinets with small drawers, each labeled with a different plant species — sits on a table with a sign-out sheet and a native plants guide.

Visitors are invited to check out — and keep — up to three seed packets per visit. Each packet is labeled with the species’ common and botanical names, plus its light, soil moisture, watering and cold stratification requirements, if any.

Minus the late-return fees, seed libraries work much like traditional ones — Parkway Central Library even has its own free seed library with vegetable, fruit, herb and flower seeds. With a mission of making native seeds as accessible as those of popular garden crops, The Discovery Center’s library now serves as a resource for free packets of high-quality, verified-native seeds.

The library is also a continuation of the work that The Discovery Center and Audubon Mid-Atlantic have been doing across Southwest Philadelphia with the Pollinator Network, a partnership between the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), Thomas Jefferson University’s Park in a Truck program, the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum and the National Wildlife Federation.

With the network’s grant funding provided by the NFWF Delaware River Watershed Conservation Fund coming to an end this summer, Bakeman and staff at The Discovery Center hope to use the seed library to continue connecting Philadelphians to native seed.

“We’ve been able to do a lot of on-the-ground work helping to install native plants in a lot of gardens and vacant lots across the neighborhoods,” says Robin Irizarry, manager for the Delaware River Watershed Program for Audubon Mid-Atlantic. “But this is an additional way that we can help provide resources to gardens who are trying to introduce more biodiversity to their spaces.”

Sowing Native Seeds

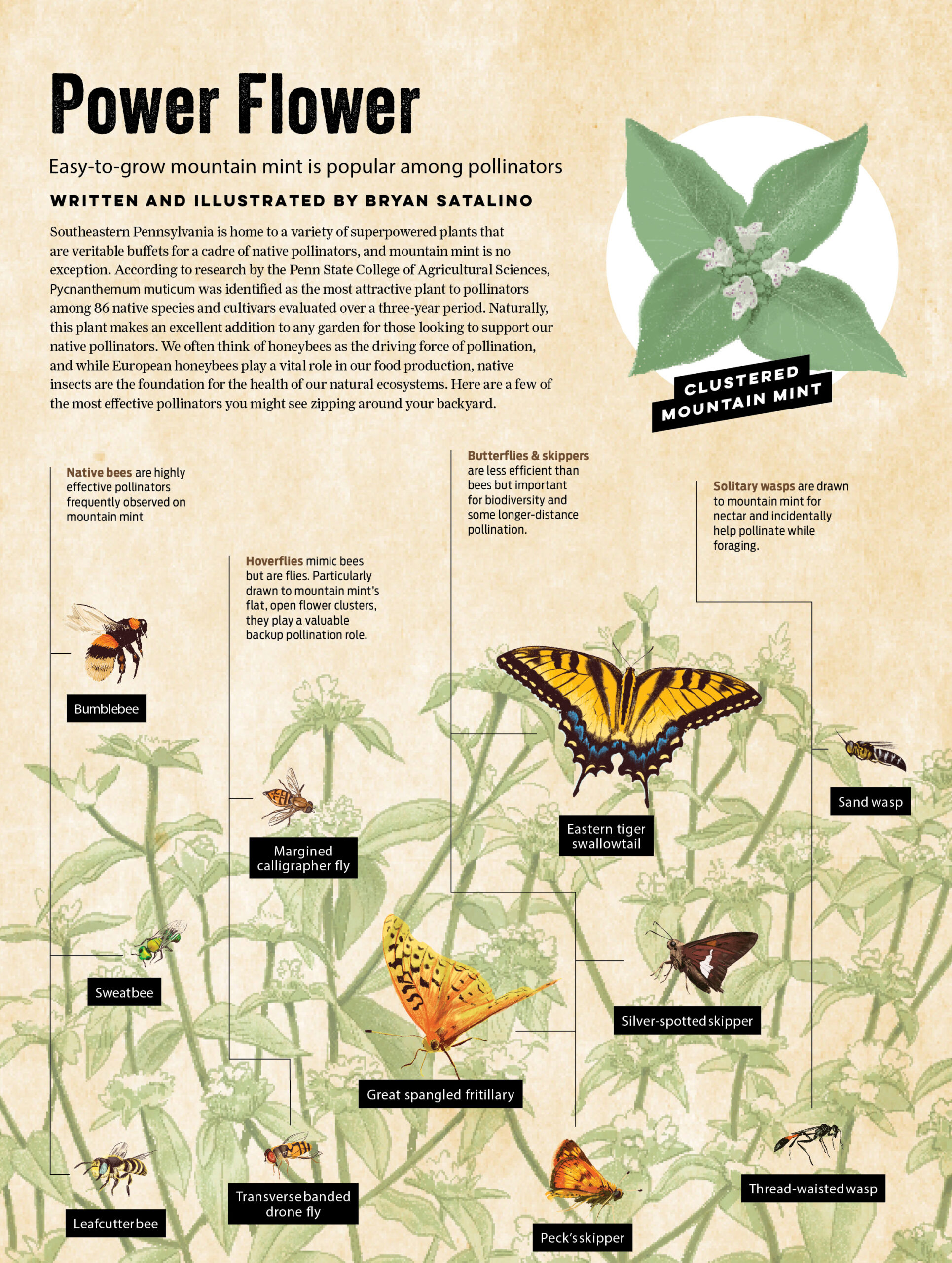

The word “native” refers to all plant species that could be originally found in a particular area. In the case of this library, its seeds are from species native to the Philadelphia region. And many species, like narrowleaf mountain mint and wild bergamot, can be found on the land surrounding the East Park Reservoir.

“Not only are they going to be ready to be grown in the ground that we live on already, but they’re going to be beneficial for the pollinators and other wildlife that use them, either as food, habitat or to nest,” says Meagan Mendoza, program coordinator for the Delaware River Watershed Program.

Pollinators such as birds, butterflies and bees are responsible for about a third of the world’s food crops — but many of their populations are declining globally due to habitat loss and disease.

Many of our region’s insects have specific relationships with certain native plant species, says Irizarry, and these delicate interactions support critical bird populations, which in turn support other wildlife. “In the springtime especially, when birds are raising young, most of those birds are predominantly finding insects for their young to eat. They need that protein, and being able to provide the full web of plants that’s necessary to support all the critters that we enjoy seeing in our neighborhood is really important.”

The seed library has a range of educational materials with information for growing native plants and a suggestion box where users can offer feedback. Bakeman also curated a cheat sheet with notes and tips for each of the 24 species currently in the library, so that visitors of all skill levels can take advantage of the seeds.

In addition to supporting critical wildlife, she hopes that community members can use the seed library to combat feelings of hopelessness about the future of our environment.

Do you have a yard? Do you have community gardens? Do you have a tiny strip of land between sidewalks? That can be a restored habitat. And I think people are looking for a way to take that action and be a force of good for the things they care about.”

— Taylor Bakeman, volunteer

“Do you have a yard? Do you have community gardens? Do you have a tiny strip of land between sidewalks? That can be a restored habitat,” says Bakeman. “I think people are looking for a way to take that action and be a force of good for the things they care about.”

In the weeks since the library’s launch, Mendoza has already observed folks with a variety of gardening experiences checking out seed packets. “I’ve got some native seed connoisseurs. But I’ve also seen a little kid and his mom come up, and he had just learned about native seed, and he just wants to try and learn and see if he can do it. So there’s a very large range of people that we’re reaching with this. It’s supposed to be accessible for everybody.” The seed library has distributed more than 1,200 seed packets as of the end of April, Mendoza says.

Bakeman and Mendoza acknowledge that there is a learning curve when working with native seeds. Unlike everyday ornamental plants, many native seed species require cold stratification, a process of exposing seeds to cold, moist conditions to break dormancy and encourage germination. One stratification technique that Mendoza and Irizarry are trying this year is growing seedlings in milk jugs that are refitted into mini-greenhouses.

Making one is easy: empty and rinse a milk jug, then cut it in half horizontally. Then, after filling the bottom of the jug with soil and planting and watering the seeds, tape the top of the jug back on and leave it outside through the end of winter. “You can let it go through that freezing and thawing process during the winter, rather than having to put it in the fridge,” says Mendoza. “It doesn’t work every single time, but it’s a cost-effective and accessible way for people to start cold stratification.”

Bakeman says that the milk jug provides an “ideal scenario” to let nature take its course with stratification. “It’s sort of beautiful if you look at it: the ecosystem has fine-tuned itself so well to drop the seeds at this time, make sure they’re exposed to cold for this time and make sure they’re coming up in just the right conditions to thrive.”

Putting Down Deeper Roots

Since the opening of The Discovery Center in 2018, the East Park Reservoir is once again accessible to community members after being closed to the public for 48 years. The seed library is one of many projects that are deepening ties between The Discovery Center and the surrounding neighborhood, and its launch this spring has led to budding collaborations between the center and Strawberry Mansion High School.

Matthew Byrne, 35, a science teacher at the school, began having his students work with native plants about four years ago. After the pandemic, and having spent a few summers working with native landscaping on his own, he felt that planting native seeds would be a transformational activity for his students — one that could also help beautify the campus.

Being the only neighborhood high school left in North Philly that’s not charter, I think it’s important that we have a green and welcoming space.”

— Matthew Byrne, teacher, Strawberry Mansion High School

“Being the only neighborhood high school left in North Philly that’s not charter, I think it’s important that we have a green and welcoming space,” says Byrne. “With the native plants we started growing a couple of years ago, we finally were able to see some monarch butterflies in the milkweeds last year.”

In Byrne’s biology and elective science classes, his students learn how to stratify, germinate and grow native plants. He says native plants are an important learning tool in his classroom, because they teach students about the diverse wildlife that exists in Strawberry Mansion and in nearby Fairmount Park.

“I want to try to push the idea of students taking these [seeds] home and starting their own gardens,” Byrne says. “In previous years, we haven’t had enough, but with the seed library, now we have an excess.”

The Discovery Center’s classroom partnership with Byrne has not only expanded his seed stock and provided a free resource for his students; Mendoza says that the center also provides lessons on native plants and pollinators and on-the-ground support with planting natives on school property.

Earlier this year, Byrne’s students planted several varieties of native plants using the milk jug method. Many of the jugs have already sprouted seedlings of dense blazing star, swamp milkweed, sneezeweed, gray goldenrod and New England aster. When these plants are big enough, some of them will find permanent homes in the garden beds lining the school’s entrance.

“That front area, four years ago, had nothing there,” says Byrne. “Now, we’re hoping to have a fully native landscape out there.”