In Philadelphia, there was once a large public park where humans had previously intervened but where nature was reasserting itself. Residents flocked there to leave the noise and rigidity of the city grid behind and bathe in the wild unruliness of trees and meadows. This was a world unto itself, but not for long: one day word came that chainsaws and bulldozers would soon arrive to chop down trees and flatten the earth, making room for the straight lines and ecologically-bereft landscapes of sports fields and picnic greens.

But those who loved the trees fought back. After all, this was the Wissahickon under threat. The year was 1937.

The above, of course, also evokes the contentious, present-day redevelopment of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park in South Philadelphia. History repeats itself in many ways, and here in Philadelphia the controversy around the $250-million FDR Park overhaul is but the latest manifestation of a long-running tension over what kinds of public parks the city’s residents get.

Much has been written about the fight over FDR, but what that conversation often lacks is context: who has traditionally decided who gets what in their park, why did they decide as they did, and how have those decisions impacted where we are today?

The search for these answers expands the scope of inquiry beyond FDR, to Bartram’s Garden, Tacony, Pennypack, Cobbs Creek and the core of Fairmount Park. It suddenly stretches to just about every neighborhood in Philadelphia, to every parcel of land unburdened by buildings or streetscape.

What are Philadelphians getting in their parks? And why?

“A Greene Country Towne”

Green space was engineered into Philadelphia’s built environment from the get-go. In 1682, surveyor Thomas Holme, at the request of William Penn, laid out a grid for the city that included four public squares still in existence today: Logan, Franklin, Washington and Rittenhouse. Further, plotlines left room for private outdoor gardens for many residences, all in an effort to best the crowded, clamorous cities of England.

But another motivating factor was Penn’s vision of a more equitable city, where beautiful green spaces were public property and not the privately-owned European gardens whose access could be capriciously controlled by aristocratic owners.

“This sense of needing green spaces, or needing places to … assemble and do whatever it was you wanted to do, has always been [in Philadelphia],” says Elizabeth Milroy, professor emerita at the University of Pennsylvania and author of a seminal book on the history of the city’s parks, “The Grid and the River: Philadelphia’s Green Places, 1682–1876.”

And as Milroy points out, true wilderness was also easily accessible for early Philadelphians into the 1800s, as development hugged the Delaware River, leaving forested lands within walking distance.

“The whole western section of Philadelphia was forest until 1877. I mean forest. You could get lost just walking west of Fifth Street,” Milroy says.

But as the city’s population increased throughout the 19th century and the Industrial Revolution rolled on, greenscapes began to give way to gray. Suddenly, country estates along the Schuylkill River became prime targets for heavy industry. Shielding the local watershed of the newly constructed Fairmount Water Works from pollution is often cited as motivation for establishing Fairmount Park along the city’s western flank, but Milroy says that was a convenient excuse for those interested in conserving the surrounding landscapes against encroaching development.

By 1867, these energies crystallized into the formation of the Fairmount Park Commission, a semiautonomous city agency that for the next 140 years collected public lands throughout the city — from Fairmount Park proper to the Wissahickon and Pennypack — and exercised great control over their development and use.

Creating Recreation

Who and what is a park for? The Fairmount Park Commission had to grapple with these questions.

Initially the conservation of the vast lands of Fairmount Park grew out of a nationwide 19th-century “parks movement” that also birthed New York’s Central Park and counted Ralph Waldo Emerson and landscape gardener Andrew Jackson Downing among its luminaries. Proponents sought to provide a sense of cleansing open spaces to cities increasingly wracked by race riots and other social ills.

“There was a growing sense that by providing public parks that are actually managed, public behavior will be improved,” Milroy says.

City parks were supposed to give city people places to go to expel their energy. Ball fields, golf courses, slides, picnic areas, tennis courts, et cetera, et cetera.”

— Kate Cowing, architectural conservator

Milroy says there was a classist undercurrent within the Fairmount Park Commission from the beginning, however. Many initial supporters of conservation, and thereafter much of the commission’s leadership, were elites, including members of the Widener and Price families. By the turn of the 20th century, critics were complaining that the commission wasn’t doing enough to serve the needs of an expanding and diverse metropolis.

“Forming the east and west [Fairmount] park: great for the people of West Philadelphia. Not so great for the people who lived in Port Richmond,” Milroy observes.

Challenges to the status quo emerged. In 1888, the independent City Parks Association formed to create public parks in other areas of the city, eventually helping to facilitate the creation of Bartram’s Garden, FDR and Pennypack. Kate Cowing, a Philadelphia-based architectural conservator who has also studied the history of the city’s parks, adds that at the dawn of the 20th century, a national park reform movement emerged to champion active recreation over passive contemplation in public parks.

“City parks were supposed to give city people places to go to expel their energy,” Cowing explains. “Ball fields, golf courses, slides, picnic areas, tennis courts, et cetera, et cetera.”

By the early 20th century, City Hall began to invest in recreational infrastructure such as playgrounds throughout Philadelphia and formed a Bureau of Recreation to oversee the efforts. Successive administrations butted heads with the Fairmount Park Commission over its perceived reluctance to promote more active recreation, and by 1928 a national report targeted the commission as one of the country’s worst laggards in adapting to changing tastes.

Soon, the tensions came to a head in the Wissahickon Valley. In 1937, word emerged of a federally-funded plan to vastly overhaul the park, through the installation of dozens of picnic areas, bathrooms, tennis courts, baseball fields, vending facilities and other improvements. While powerful opponents in Chestnut Hill were able to greatly curtail the proposal, $16 million in federal money went into revamping other city parks during the 1930s.

One of the era’s notable additions: a golf course at FDR Park.

Money Doesn’t Grow on Trees

Money has always been a problem for Philadelphia’s green spaces, even for those original public squares: Well into the late 1700s, cattle, brick kilns, flooding and even public executions were common sights in Rittenhouse Square, with residents often petitioning the city government to spend money on improvements and sometimes funding it themselves when no money shook loose.

Milroy’s research reveals that funding concerns continued into the era of the Fairmount Park Commission. Even though wealthy benefactors supported the commission’s formation and bequeathed parcels of land, ongoing maintenance and improvements of the parks relied on funding from the city. Even in the 1870s, when Fairmount Park hosted the Centennial International Exhibition, Philadelphia spent an average of only $223,000 on the park’s upkeep, Milroy found, less than a third of what New York spent on (considerably smaller) Central Park.

By the 1930s, concern over the commission’s opaque finances and lack of focus on recreation was drawing state-level scrutiny. The commission began to relent.

“Suddenly tennis courts start popping up,” Milroy says. “That’s part of the reason why [these courts] seem to be just sort of plugged into places like East and West Fairmount Park.”

Still, concerns about the commission’s stewardship of the city’s parks persisted. City Hall continued to increase its own recreational infrastructure, including the 1952 creation of the Department of Recreation. And City Council regularly clashed with the independently-run commission. In 2010, it was Philadelphians themselves who voted via referendum to combine the commission and prior Recreation Department into the new Philadelphia Department of Parks & Recreation, bringing management of Philadelphia’s vast parks and recreational assets fully under the auspices of city government. A new era had arrived.

Par for the Course?

As tempting as it might be to look across the current landscapes of Philadelphia’s parks and render judgment on the outcome of these historical decisions, many of those with the power to decide what goes where say it’s just not that simple. The city is a big and complicated place with various competing — and changeable — interests. And money is ever short.

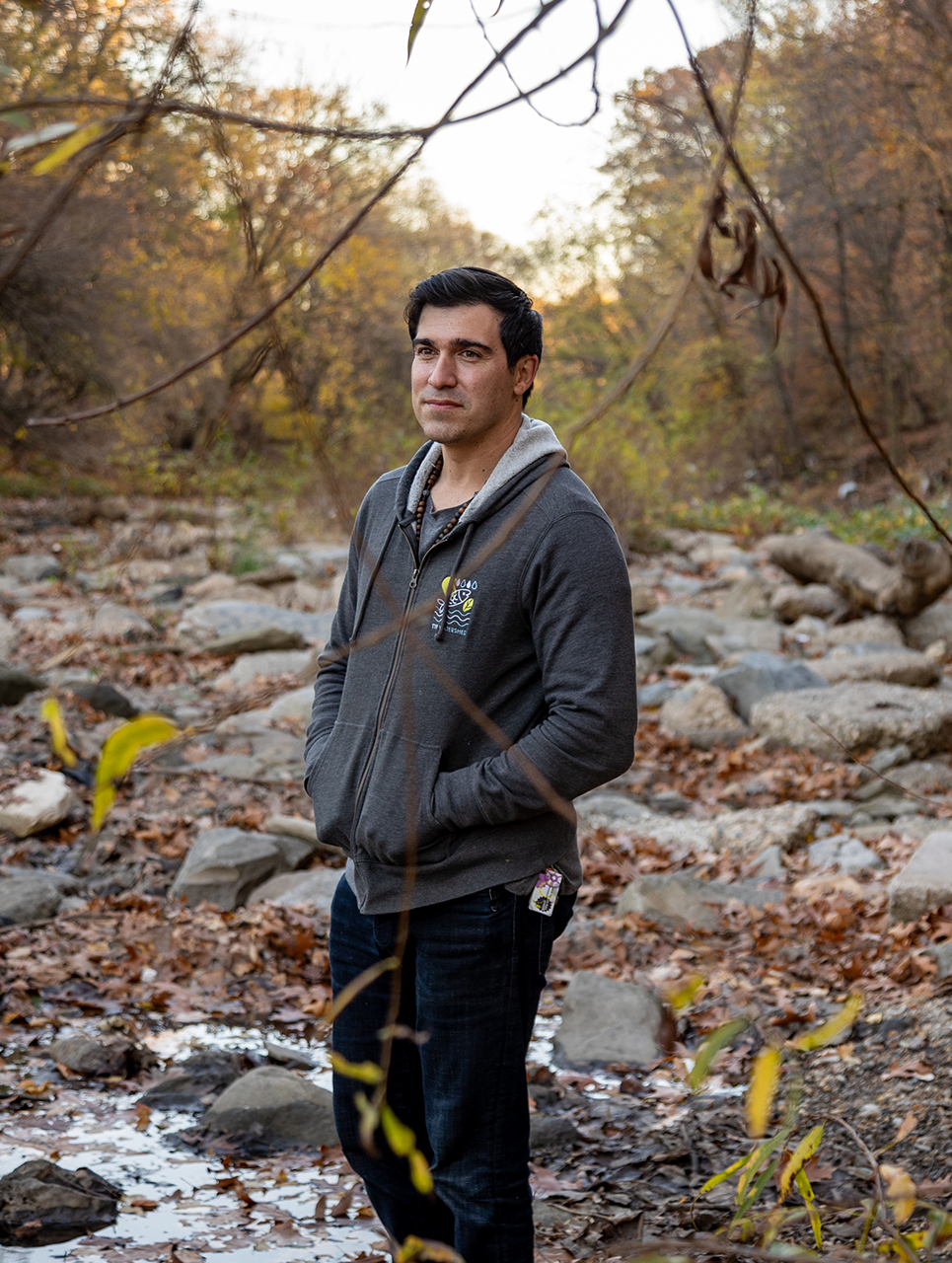

“Philadelphia is spending, per capita, on public space and recreation, a fraction of what [peer] cities are doing,” says Justin DiBerardinis, executive director of the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, a nonprofit helping steward the 30-square-mile watershed in North and Northeast Philadelphia.

Prior reporting by Grid (#163, December 2022) revealed the extent of park funding shortfalls in the city. The budget for the Fairmount Park Commission fell from 2.26% of the city’s budget in 1960 to 0.32% in 2009, the year before it merged into Parks & Recreation. More recent estimates show funding for parks at about 0.78% of the total budget — a modest rebound that still leaves it at a third of historical funding levels. Per capita, Philadelphia now spends 60 cents on the dollar on parks compared to the national average, with an unusually high amount of that coming from volunteer hours and spending by private groups, instead of municipal coffers, according to the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore.

Philadelphia is spending, per capita, on public space and recreation, a fraction of what [peer] cities are doing.”

— Justin DiBerardinis, Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership

DiBerardinis views Philadelphia’s parks as a “tremendous gift of previous generations.” But the lack of funding has resulted in serious maintenance issues, complicating the conversation about which land uses should be prioritized.

“We have thousands of acres of forested land in the city,” DiBerardinis says. “But does it have signage? Is it trailed? Does it have amenities? Are the invasives under control? Is it welcoming? Does it feel safe? These are the challenges that prevent these natural land areas from achieving that incredible dual identity of being great ecological areas … and also having a transformational impact on the lives of Philadelphians.”

Officials with Parks & Recreation identify additional priorities. Leigh Ann Campbell, the department’s director of planning, preservation and property management, notes that it now has oversight over assets as disparate as historic buildings, natural lands, recreation centers, playgrounds, street trees, parks and pools. And commissioner Susan Slawson says the department primarily makes land use decisions based on input from nearby communities and coordination with nonprofits.

“We have communities, we have neighborhoods, we have people that are very vocal about what they want in their parks, in their recreation, whether it’s passive or not,” Slawson says.

But some have criticized the city as now being too deferential to outside groups. The Fairmount Park Commission has been replaced by dozens of local “friends” groups and other nonprofits. Kevin Loughran, a sociologist at Temple University whose book “Parks for Profit: Selling Nature in the City” examines the relationship between public parks and the groups that care for them, previously told Grid (#157, June 2022) that the city’s reliance on nonprofits can lead to inequitable outcomes and also allow hidden financial interests to dictate land use decisions.

All of these thorny issues have come to a head in FDR Park in recent years, after the Fairmount Park Conservancy, a nonprofit offshoot of the former commission that still helps steward vast acreages of city parks, proposed a complete, $250-million overhaul. The redevelopment plan is a once-in-a-century opportunity for one of Philadelphia’s largest parks — and provides a window into how the system currently works.

And things certainly look ugly. Opponents of the plan went to court, unsuccessfully, to try to stop the razing of heritage trees and a burgeoning meadow on the defunct 1930s-era golf course, which will clear the way for the installation of synthetic turf fields. Critics also say the conservancy and City are giving too much deference to financial interests, as the park plans to achieve financial stability through concessions and leasing out playing fields, possibly including during the 2026 FIFA World Cup.

Anisa George, an environmental educator and leading opponent of the plan, notes that local neighborhood groups including the Friends of FDR Park and Packer Park Civic Association opposed the razing of the heritage trees. She decries what she sees as an undemocratic process, with important decisions made by the nonprofit conservancy without the same level of public oversight given to other controversial City Hall decisions.

“Where the heck is the public mandate for this process?” George asks. “Where are the videos? Where are the transcripts? Where is the recorded testimony?”

We’re confident in the fact that the plan balances activity, nature and water in the interest of the broadest possible group of Philadelphians.”

— Allison Schapker, Fairmount Park Conservancy

But Allison Schapker, chief operations and projects officer for the conservancy, who has shepherded the redevelopment plan since 2018, insists that the plan does reflect public sentiment gathered via a “community-led” process, pointing to numerous proactive and reactive public engagement initiatives in early planning stages and the fact that supporters of the plan say playing fields are sorely needed for youth sports in the city.

“We’re confident in the fact that the plan balances activity, nature and water in the interest of the broadest possible group of Philadelphians,” Schapker says.

More holistically, she believes the plan is a model for the modern era of Philadelphia’s parks. She acknowledges the city’s lack of overall funding for parks — “It’s really clear there just aren’t enough resources in our city to take care of any piece of these critical landscapes in a way that I think we all would love to see happen,” she says — and stresses the importance of thinking about dependable revenue streams.

“Conversations about the cost of maintenance absolutely need to include the understanding that natural areas aren’t free, and every piece of ground that we have in our park system requires some level of ongoing investment,” Schapker says.

Ultimately, the plans call for about 60% of acreage to be dedicated to natural areas and 40% to recreation, which she says is an overall increase toward natural areas compared to when the golf course was in operation, and also representative of the diversity of public feedback. Schapker also argues that the planned placement of those assets makes sense both logistically, with playing fields going on the perimeter of the park where they’re most accessible via public transit, and ecologically, with the playing fields situated atop the previously pesticide- and herbicide-laden golf course fairways, while a 30-acre tidal wetland is restored in the southwest corner of the park.

Asked why, if all these things are true, the plan was met with a sudden swell of public opposition upon early stages of implementation, Schapker cited a shift in the preferences of some who began visiting the golf-course-turned-meadow during the pandemic. Whether or not that observation is true, Schapker later offered another that undeniably reflects the centuries of wrangling over Philadelphia’s green spaces.

“No matter what,” she said, “a change in land use is always going to be controversial.”

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit