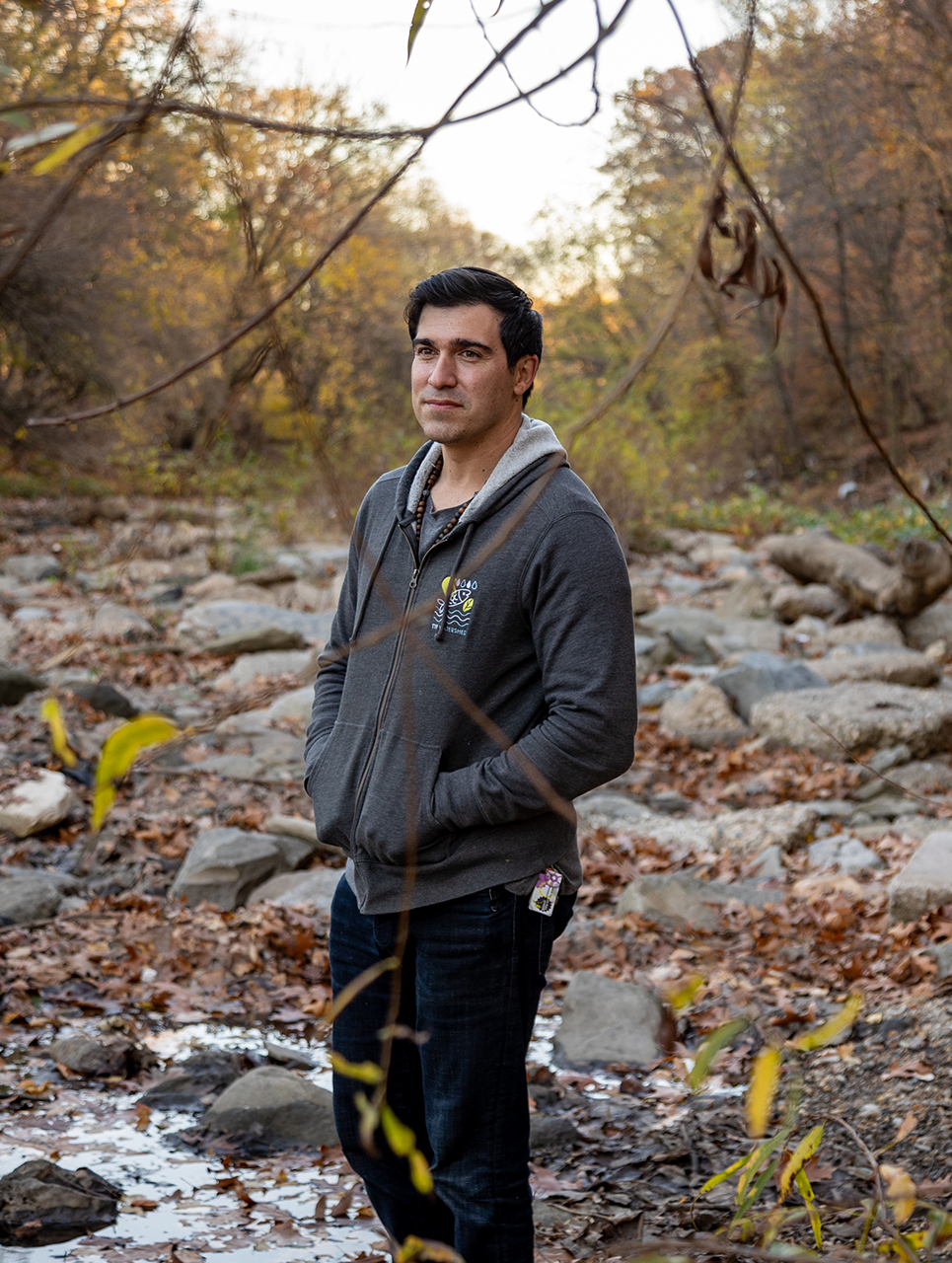

A recent PennEnvironment report found that Pennsylvania school districts are failing to keep lead out of school drinking water. Grid spoke with the executive director of PennEnvironment, David Masur, to learn more.

Why should people be concerned about lead in school drinking water? Lead is unsafe at any level, especially for kids. There’s no “safe” amount of lead in drinking water. The current standards set by the EPA allow up to 10 parts per billion (ppb) of lead, but that number is based on politics, not health. The American Academy of Pediatrics says drinking water for kids should contain no more than 1 ppb. So when a school district tells PennEnvironment they’re “within the legal limit,” that they’re “only” finding lead levels of 8 or 9 ppb, that’s still much more lead than what’s truly safe for children.

Why is it so hard to keep lead out of drinking water? Lead is unpredictable. It doesn’t just “stay put” in pipes. Environmental factors can cause it to leach into the water at any time. For example, one Philadelphia school found low levels of lead in 2016. But by 2019, that same fountain had levels hundreds of times higher than health standards. It’s like playing Whac-A-Mole. Testing won’t always reveal the full picture because lead can spike between tests. That’s why we recommend replacing fixtures rather than relying on spot testing.

Aren’t schools required to test drinking water for lead? Actually, no. School buildings aren’t covered under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. There’s no federal requirement for schools to test drinking water or report the results to the public. Pennsylvania also has weak testing standards. So when schools say, “We comply with all the laws,” they’re meeting a pretty low bar. They might only be testing one or two outlets. That’s like looking at just one corner of your house to see if you have bedbugs. It doesn’t give the whole picture.

How common is lead contamination in schools? Lead is everywhere — in rural, suburban and urban schools across Pennsylvania. It’s a bipartisan issue. But historically, many schools, especially in suburban areas, have flown under the radar. Most people can’t even name a single school board member or the superintendent of their district. That lack of accountability has allowed districts to stick with outdated practices.

Why don’t more districts replace their drinking fountains with lead-filtering hydration stations? Many districts say it’s too expensive. But data shows it’s actually very affordable. Hydration stations that filter lead, PFAS and microplastics cost between $2,500 and $3,000 each. Most districts could replace every drinking fountain for less than 0.1% of their yearly budget. It’s not a huge lift financially.

So why haven’t more districts acted? Part of it is fear. Admitting there’s a problem with lead in drinking water could make people angry. But parents are going to be even more upset if they find out the district knew about it and did nothing. Another challenge is that some school districts just don’t like being told what to do. They’ve operated independently for so long, and they want to keep doing things their way.

Are there examples of districts taking proactive steps? Yes, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are both setting the standard. Philly’s City Council closed the loopholes that allowed the school district to avoid testing. And in Pittsburgh, they just completed a multiyear program to replace fountains with lead-filtering hydration stations. If big districts like these can do it, so can smaller districts.

What’s the best solution moving forward? The simplest and most effective solution is to install hydration stations with certified lead filters. New models can filter out not just lead but also PFAS and microplastics, which is a huge health win. The technology has come a long way, and schools have options to fix this once and for all.