By Dawn Kane and Bernard Brown

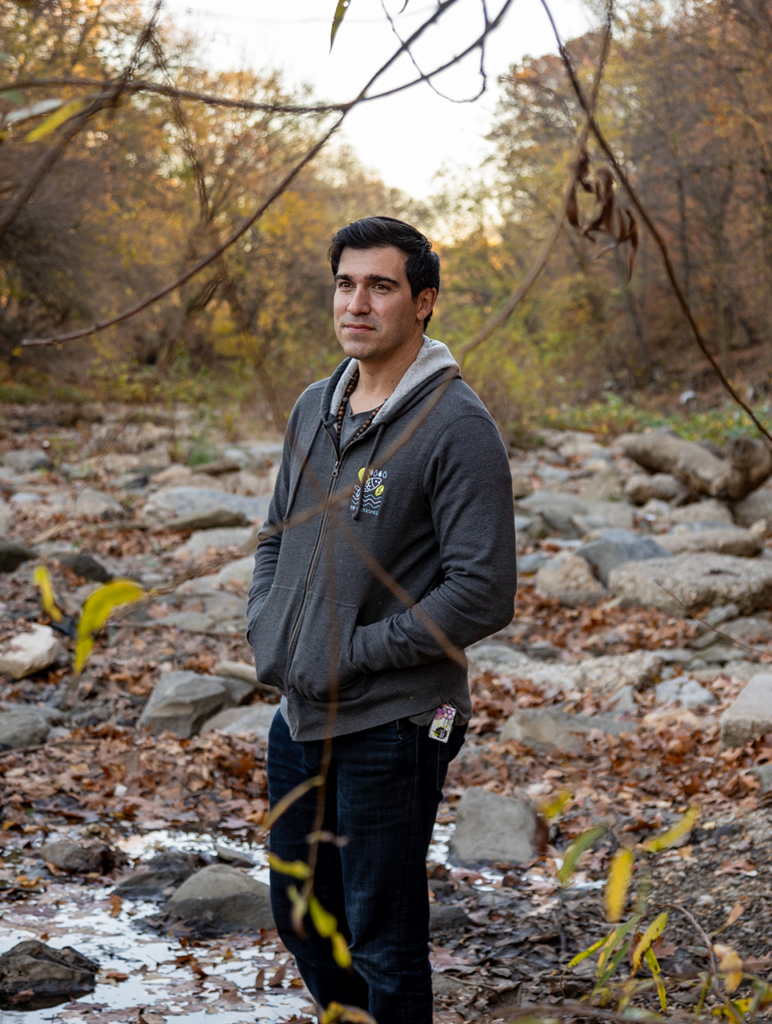

It has been nearly 380 years since blueback herring have been able to swim up Cobbs Creek beyond what is now Woodland Avenue. Back in 1645, New Sweden’s governor, Johan Björnsson Printz, built a gristmill on the waterway the Lenape call Karakung. Water-powered mills generally rely on a dam that backs the water up and then releases it as needed through an artificial channel called a mill race to turn a wheel that drives the machinery, in this case grinding grain into flour. That flour presumably fed Swedes manning a nearby fort. The location was strategic, along the Great Minquas Path, on which the Susquehannock tribe transported beaver pelts to trade with Europeans.

The Swedes lost their colony to the Dutch in 1655, and later the British took over. The dam, rebuilt who knows how many times, remains. William Penn’s 1681 map of his new colony shows “Sweeds Mill” at the same location. A 1750 map shows a “Snuff Mill,” which presumably produced powdered tobacco products, and an 1872 map showed “Paschall’s Saw Mill,” along with the mill race that channeled the power of falling water to cut logs into boards. That mill race flowed into the Passmore Textile Mill below Woodland Avenue, and in 1895 Fels & Company bought the site of the textile mill to produce their famous Fels-Naptha laundry soap.

The centuries of industrial activity that took advantage of Cobbs Creek came to a close nearly 100 years ago, but the dam still stands. Blueback herring, close relatives of American shad, spend most of their lives in the ocean but breed in fresh water — an “anadromous” life cycle. (American eels, “catadromous” fish, do the reverse, spending most of their lives in creeks and rivers but breeding in the open ocean.) The herring still bump their noses against the Woodland Dam.

The dam, which sits between the tidal and nontidal sections of Cobbs Creek, was classified as the first impediment to fish passage on the waterway (moving upstream from the ocean), according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report published in 2016. In 2003 Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) biologists documenting fish collected 19 species above the Woodland Avenue dam versus 43 species in the tidal portions of Cobbs Creek. “Most notable was the absence of anadromous and semi-migratory fish species in the non-tidal reaches (above Woodland Dam),” the Corps wrote in the report.

In 2009 PWD made a plan to take it down. It might seem like a simple matter to knock down a few feet of concrete, but things are not always as easy as they seem.

Change the name of the creek, and the same story could be told hundreds of times across Pennsylvania. European colonists and their descendents built dams to power mills. Larger dams built in the 20th century protect downstream communities from floods and provide reservoirs for drinking water and recreation. New and old dams alike block fish and other aquatic life from moving upstream, providing a compelling ecological argument for dam demolition.

But even when property owners or local governments don’t have a strong interest in creek ecology, safety and liability concerns can motivate them to dismantle old dams.

In 1978, after Pennsylvania’s third catastrophic dam failure, in which the Laurel Run Dam in Tanneryville destroyed homes and killed 40 people, the state enacted the Dam Safety and Encroachments Act, regulating dams and other water obstructions and categorizing them by hazard level. Dams are classified by their size and their potential to cause harm. For example, the failure of a high-hazard dam is expected to endanger populated areas downstream.

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection regulates the safety of the state’s dams, the majority of which are privately owned and serve purposes ranging from recreation to hydroelectric power. If the dams are determined to represent a safety hazard, owners must provide the state with proof of financial responsibility to continue a dam’s operation.

Dams don’t need to fail to be dangerous. A low-head dam spans the width of a river and can create a placid pool upstream that invites fishing and swimming — without any obvious sign of danger. However, water passing over the dam can create a hydraulic action just beyond the barrier that can trap people underwater. In 1998, the state enacted legislation calling for owners to post warnings about the potential dangers of these kinds of dams, also known as “run-of-the river dams.”

The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that 50 people drown annually across the country at these kinds of dams. In Harrisburg, a reporter for PennLive found that while deaths at the Dock Street Dam, a “killer” dam, had gone untracked, there had been 30 known fatalities between 1935 and 2018.

In 2013 Brandon Boyle, 13 years old, drowned while playing around a dam on Pennypack Creek in Northeast Philadelphia, at a spot where, three years before, a 20-year-old swimmer had lost his life.

“In my experience, [dam ownership] has been kind of a liability,” says Jacob Helminiak, hydraulic engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Philadelphia District. If a privately owned dam fails to meet safety regulations, owners are expected to upgrade it to meet those standards. “Oftentimes, dam removal comes into the conversation then if it costs less.”

Certainly the single biggest benefit of dam removal are the migratory fish. The Delaware River and all of its tributaries are loaded with migratory fish.”

— Erik Silldorff, Delaware Riverkeeper Network

Whatever the motivation to do so, removing a dam has the potential to reconnect waterways and benefit the wildlife living in them. “Certainly the single biggest benefit of dam removal are the migratory fish. The Delaware River and all of its tributaries are loaded with migratory fish — some of our most important species in these ecosystems,” says Erik Silldorff, restoration director and senior scientist at the Delaware Riverkeeper Network.

The Musconetcong River in northern New Jersey had been dammed since the 1700s, keeping out fish that could have entered from the Delaware. After the removal of four dams on the Musconetcong between 2008 and 2017, American shad were spotted just upstream of the former site of the Hughesville Dam, the last one to be removed.

In the Chesapeake watershed near Baltimore, Maryland scientists monitoring fish in the Patapsco River above the site of the former Bloede Dam found that alewife and blueback herring were returning upriver.

Dam removals starting near the mouths of the two rivers allow migratory fish to move freely, but even dam removals within river systems that are still blocked from the ocean can make a difference for fish that stay in freshwater, such as white suckers, which can live in smaller tributaries when young and in deeper sections of larger waterways as adults. Before the Manatawny Creek dam near Pottstown was removed, researchers marked fish below and above the dam. After the dam was taken down, they found marked fish on the other side of where the dam had been. These kinds of fish movements are critical to native mussels, which as larvae hitch rides on fish gills before settling to the bottom. A dam that blocks fish also cuts off mussel populations.

The Cobbs Creek Fish Passage Plan, approved by the Corps of Engineers in 2017, called for partial removal of the Woodland Dam, inclusion of a fish ladder (aka a rock ramp) and stream restoration. Fish would be able to swim up a series of shallow rocky steps to get over the lowered dam, as shown in a project description issued by PWD.

It looks like it should be more simple than it ends up being.”

— Jessie Thomas-Blate, American Rivers

On paper it looked straightforward enough, but dam removals aren’t always straightforward.

“It looks like it should be more simple than it ends up being,” says Jessie Thomas-Blate, director of river restoration at American Rivers. “Regardless of where it is or who owns it, you have to do some kind of design, hire engineers to look at the site, and design for deconstruction.” The design can become more complicated if there is other infrastructure in or near the dam, such as a road running along the top or sewage pipes running under it. Dams also tend to trap sediment over their lifespan, so removing them can release pollutants that have been banned for decades.

After the initial design steps, dam removals require a lengthy permitting process. PWD submitted their plan for the Woodland Dam to the Corps of Engineers in 2009, and it was approved in 2017.

In 2023 all appeared to be on track for work to begin soon, but in December of that year a PWD representative informed Grid that the project was on hold. According to Stephen Rochette of the Corps of Engineers, the project was paused due to the City’s “inability to obtain the necessary real estate easements that enable construction to move forward.” (Grid reached out to PWD for more information about the difficulties gaining access to the property along the dam but did not receive a response before going to print.)

Until the City can access the land needed to complete the project, the Woodland Dam will remain a barrier to migrating fish. Every year another generation of blueback herring will make it to the Woodland Dam and, finding no way around it, end its journey there, thanks now to barriers of law and property ownership as much as of concrete.

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

Any updates on obtaining the necessary easements to resume the Woodlands Dam project? Would it benefit from community support?

I haven’t heard anything new. I imagine some advocacy couldn’t hurt.