The Big Favorite wants to redirect our worn out panties, briefs and bras into the zero-waste economy — but there’s a catch. Used polyester-infused underwear is not currently suitable for recycling. With no place left to go but the trash can, undies join the estimated 11 million pounds of textiles dumped in landfills yearly.

In 2020, The Big Favorite (TBF) founder Eleanor Turner launched her sustainable clothing business with the belief that growing numbers of consumers want to break the clothing waste cycle, cutting back on the estimated 89 pounds of clothing the average American consigns to landfills annually. Turner thought plastic-free underwear would be the best foundation on which to build her innovative company, initially located in Philadelphia and now based in Yardley, Bucks County.

Our garments are so comfortable, customers tell us they forget they are wearing them.”

— Eleanor Turner, founder of The Big Favorite

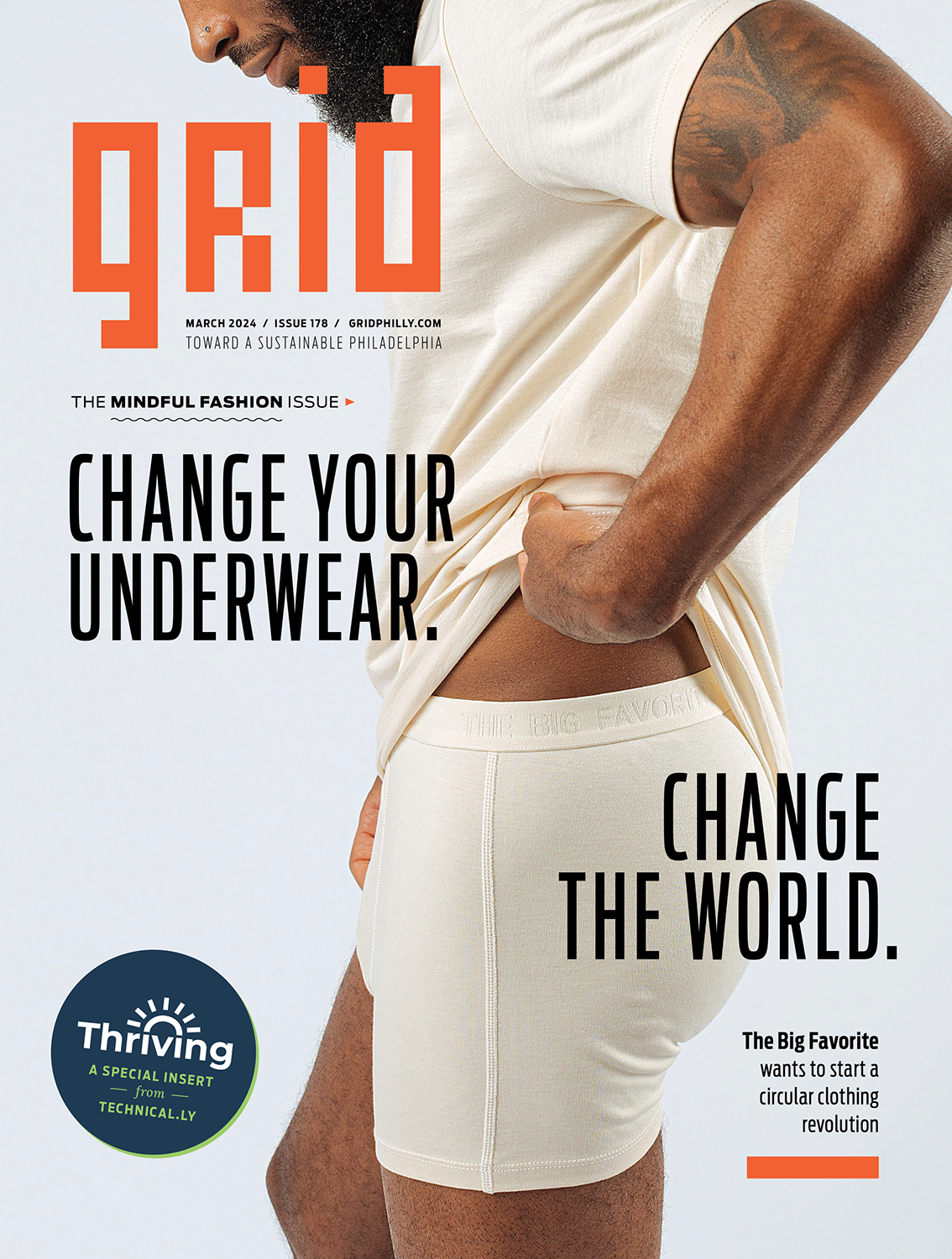

TBF’s mission is to create a zero-trash standard for their products. Their “base layer” line of panties, sports bras, briefs and tees showcases Pima cotton, known for its superior comfort, durability and recycling ease. “Our garments are so comfortable, customers tell us they forget they are wearing them,” Turner says. TBF customers are encouraged to wear out their purchases and send them back clean. TBF pays for shipping, sanitizes the garments and passes them to a third party to be repurposed into yarn.

While Pima cotton may be familiar to discerning consumers, less well known is that Pima is native to Peru, where it was originally cultivated by Indigenous peoples, Turner says. TBF contracts with Peruvian manufacturers able to meet TBF’s standards of fair labor practices, energy conservation and environmental impact. Mindful of the extensive greenwashing in the fashion industry, Turner travels to Peru to walk the sewing line and facilities. The business owner wants her customers to trust that the promise of organic materials, natural dyes and material reuse behind each purchase has been verified.

As TBF’s sole full-time employee, Turner is no fashion novice. Previously, she acquired industry experience and professional contacts as a designer for brands like Tory Burch and J.Crew. She learned that fostering creativity and experimentation is critical to business success. But she also discovered that adding polyester to cotton is cost-cutting magic. As companies wove more plastic into clothing to balance retail prices with profit, she saw an opportunity to create a sustainable alternative literally from the bottom up, making naturally-dyed undergarments from organic fibers. Currently, TBF sells online direct to consumers but expects to expand its distribution in 2024 after completing what Turner describes as a “thoughtful testing of retail and wholesale channels.”

Starting with a small, unisex product line of thongs ($16), briefs, tees and organic Pima turtlenecks ($65) enabled TBF to do what every start-up must accomplish: keep the business simple, prove the concept and experiment to find the best solutions. TBF’s added challenge was building a resource-replenishing circular system — rare in an industry plagued by waste.

Despite Vogue magazine’s recent claim that “the future of fashion in the 2020s is circular,” consumer response has not turned out as Turner had expected. She had thought customers would support TBF products because of its mission, especially after articles in Elle, Marie Claire, and Fast Company magazines praised the company’s “circularity.” Instead, Turner says, her products are known for their “fit, quality and support for natural biomes.” Mission, it appears, matters less than anticipated. Participation in TBF’s return/recycle program still falls short of its ambitious goals, while comfort, style and convenience predominate as consumers’ main motivators.

Ali Howell Abolo, associate professor and program director of fashion design at Drexel University, describes the prevailing market forces succinctly. “Fast fashion companies are continually pushing overconsumption.” While some may claim to support sustainable practices, Howell Abolo questions how inclusive and valid such claims are. “We need to think about the cultural, social, economic and environmental impacts [of a business] all as aspects of sustainability.”

Kimberly McGlonn, founder of the Philly-based sustainable clothing company Grant Blvd, knows how tough it is to change the conversation around fashion. Since 2017, she has nurtured her mission-driven enterprise, and it hasn’t gotten much easier. As consumers, “we are failing with aligning our consumptive behaviors with an understanding of what is happening in the areas of climate catastrophe and social justice,” McGlonn believes. She questions why we are willing to pay far more for a flashy designer label than it costs to produce, but seem resistant to put a premium on goods that redefine “luxury” by being sustainably and ethically manufactured.

As Turner looks to grow her business, she faces an uncertainty many founders encounter. Pitted against the massive marketing budgets and economies of scale enjoyed by established brands, how can innovative small companies change consumer behavior? Howell Abolo sees the potential for change as more students in fashion programs arrive with baseline knowledge in sustainable design. Even more importantly, she says, “Newer generations bring an awareness of the climate crisis, understand a need for change, and they want to change.”

With mission-driven companies like Grant Blvd and The Big Favorite and

sustainability-minded young designers shaping fashion, customers can’t claim a lack of alternatives. So what will be the tipping point that lures consumers away from fast fashion to become champions of sustainable clothing? Will it begin by recycling our underwear? Howell Abolo hopes more companies begin taking eco-friendly actions. “Consumers of many different target markets are interested in being more sustainable,” she says. “We’re seeing more interest in clothing repair, buying quality over quantity.” The huge dilemma is making sustainably-produced products affordable. She urges fashion pioneers, “don’t give up.”

Before launching her business, Turner discovered that, in the 1930s, her great-grandfather owned a company called The Big Favorite that made workwear for American laborers. Dickies eventually acquired the company and retired the name. Excited by this legacy, Turner reclaimed and reinvented the TBF brand. She sees a through line connecting the practical clothing her great-grandfather made with her contemporary garments. “They are all built for American life … and for what people need,” she says. “We just need to be comfortable. I like to think he’s proud.”

We don’t just need to make more ethical goods affordable; we need to make manufacturers of fast fashion pay for its actual environmental and health costs, which are borne by people and environments usually far away and out of sight of those who buy the goods. Until this changes, very few consumers will make different choices, because fast fashion is just SO much cheaper, in addition to having the allure of bright dyes, sexy stretch, and tech-fabric properties.