In the early 1700s, botanist John Bartram surveyed his farmland abutting the banks of the Schuylkill River in what is now Southwest Philadelphia and had an idea: build a garden for his beloved plants. Approaching its 300th anniversary, the modern Bartram’s Garden is a National Historic Site and a gem of Philadelphia’s park system.

But the landscape around Bartram, and indeed much of the city, looks vastly different than it did three centuries ago. Layers of development have turned Philadelphia into one of the nation’s densest cities, and a collision of socioeconomic factors have also made it one of its poorest.

Bartram’s executive director Maitreyi Roy sees incredible potential for the gardens to serve this complex metropolis. There, she and staff have prioritized reconnecting some of the most underprivileged neighborhoods in the city to the river, where residents can fish, boat and otherwise relax. Since the murder of George Floyd and the racial reckonings that ensued in the summer of 2020, the work has taken on new urgency. Bartram’s is making progress as more neighbors utilize the park and access the river.

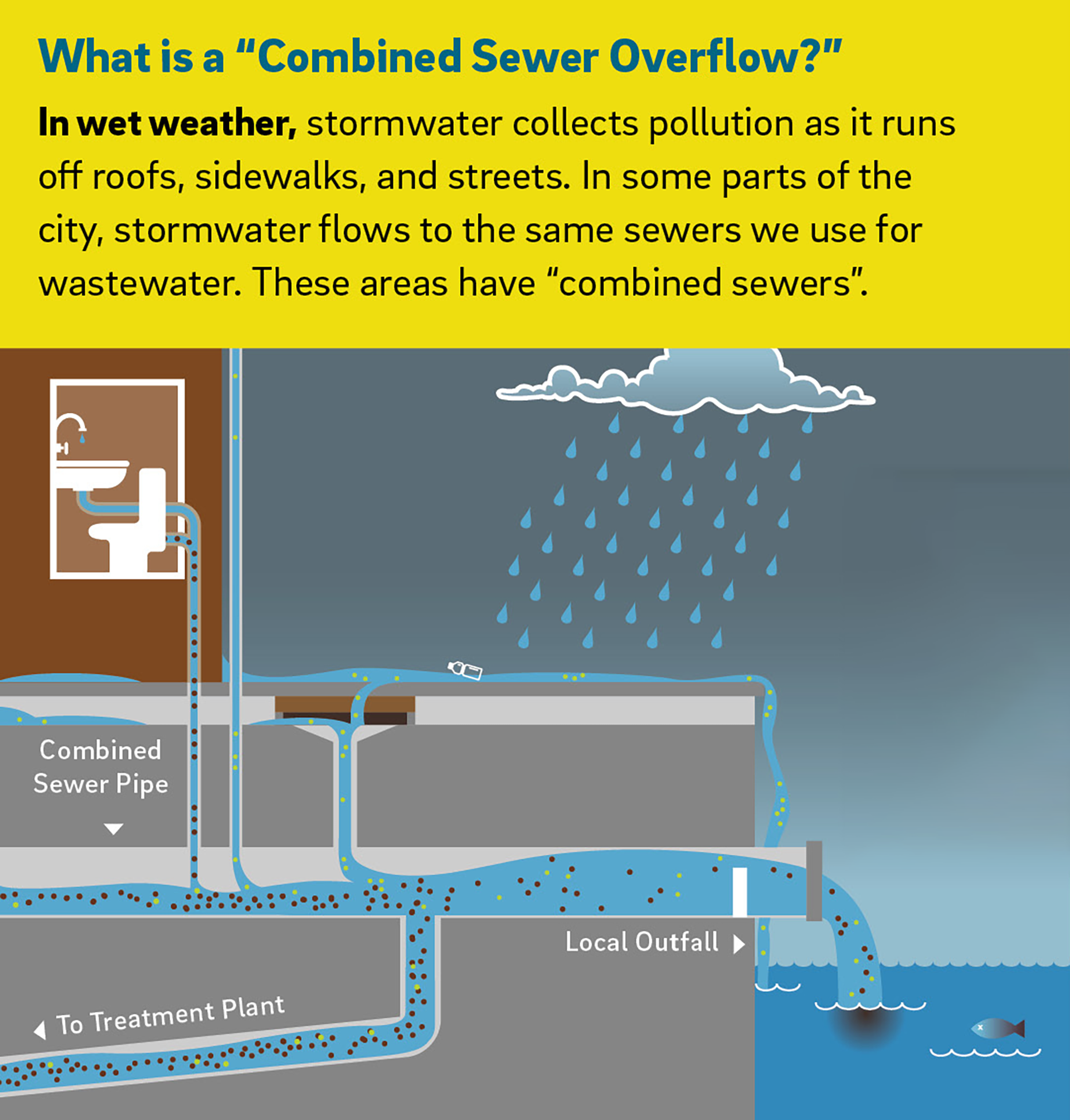

But there’s a problem. Dozens of times a year — basically every time there’s a decent rain — the water becomes off-limits. Pollution can enter a major river like the Schuylkill from a million places, but Roy is particularly worried about Mill Creek. Located just upstream from the garden, the creek was one of several in Philadelphia paved over and converted into a sewer in the 19th century. Now when it rains and the sewer system’s capacity is exceeded, the creek funnels raw sewage directly from the homes and businesses of Philadelphia into the Schuylkill. The overflows bring E. coli and other threats to the water, making it unsafe for recreation and forcing Bartram’s to cancel events to protect their visitors.

“Our rivers are our lifelines,” Roy says. “I’m not saying all residents need to be paddling on the water. But for our city to be livable, our rivers need to remain clean.”

Across Philadelphia, there are 163 outfalls like Mill Creek, where vast underground networks of aging sewers, designed in an era with less concern over the pollution of waterways, can overflow into the Schuylkill, Delaware, and Tacony and Cobbs Creeks. Indeed, it’s a challenge familiar to hundreds of older cities across the country, drawing significant attention in recent decades from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

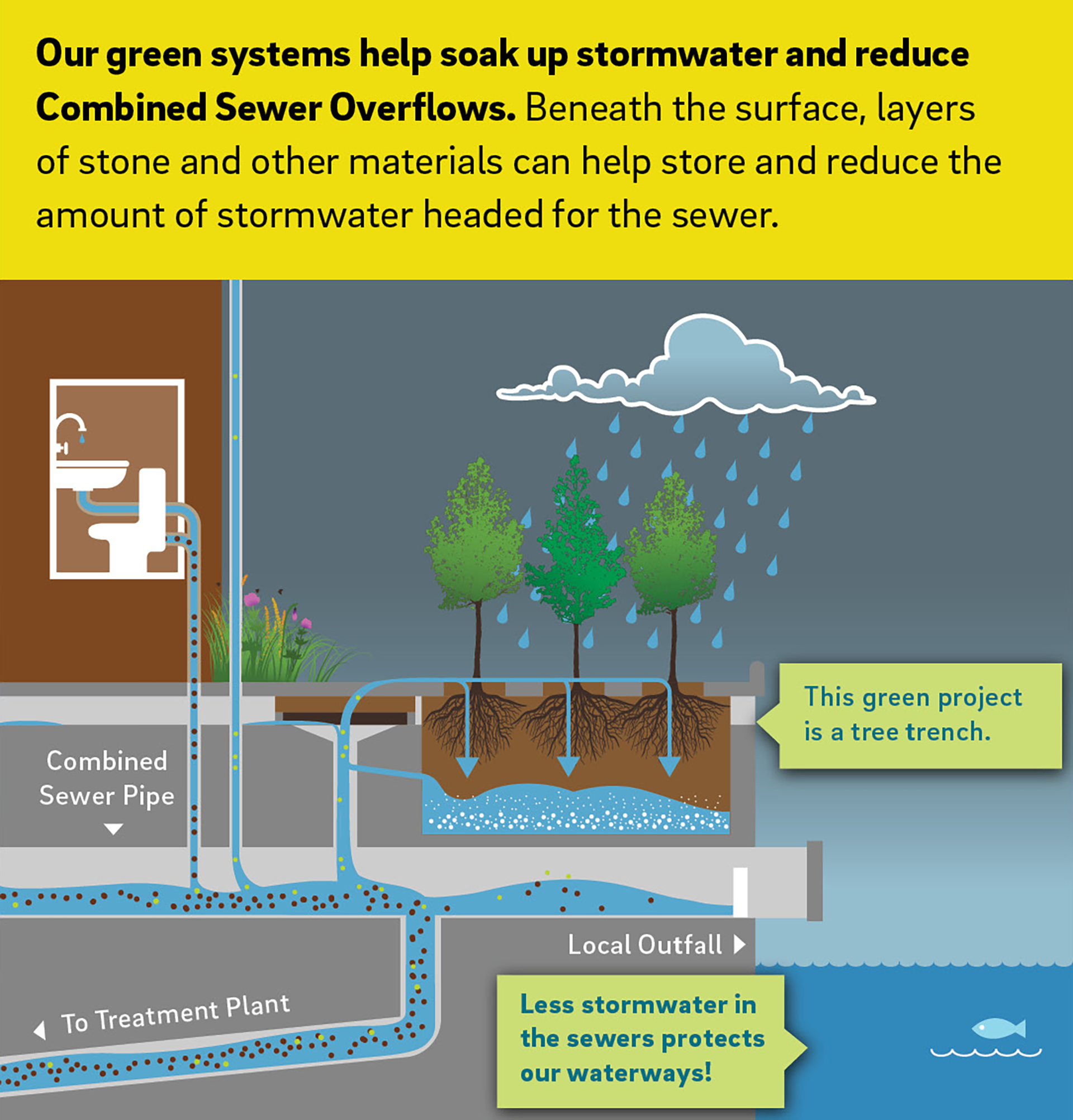

The stakes are high here in Philadelphia, where the City is halfway through a 25-year agreement with regulators to cut down on the billions of gallons of sewer water that pour into area rivers and creeks each year. And the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) has pioneered a nationally-innovative approach, using “green infrastructure” such as rain gardens, green roofs and permeable surfaces to soak up stormwater, as opposed to more traditional,

concrete-and-steel engineering methods like underground holding tanks.

For many reasons, Green City, Clean Waters, as PWD named the program, has won widespread acclaim since its implementation more than a decade ago. In addition to reducing sewage overflows, green infrastructure can also beautify a neighborhood, offset summer heat and cost less than traditional infrastructure, proponents say. Lisa Jackson, a former EPA administrator under President Barack Obama, went so far as to deliver a speech in Philadelphia on the program’s merits as it kicked off in 2012.

“The techniques under this program will work with Mother Nature, and use natural environments to filter runoff and relieve pressure from the city’s 3,000 miles of traditional sewer infrastructure,” Jackson said. “It is our hope that lessons from Green City, Clean Waters will translate to other cities as well. We want to see the benefits of green infrastructure taking hold in other large metropolitan areas.”

But in quiet corners, critics of the approach have started to question just how well it’s working. The concern, they say, is whether the benefits of green infrastructure have been oversold, or at least overridden by climate change. And the kicker is that the cost of the multi-billion dollar program falls primarily on Philadelphians themselves, who are financing the program through increases to their water bills. If the City doesn’t get it right, Philadelphians will likely have to pay more in the future for a method that works better.

In partnership, Grid, Chestnut Hill Local and the online newsroom Delaware Currents spent several months examining the City’s program. This reporting is the result of reviews of more than a decade of PWD materials on the program, as well as interviews with more than a dozen engineers, clean water advocates and other experts about its efficacy.

What emerges is a complicated portrait, one that transforms with a slight change of perspective, and traces some of the deepest fault lines of American society.

On paper, PWD is currently hitting every single target that the EPA and Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection [DEP] are requiring of it. Each year, the water department releases an annual report with data on sewage overflows into waterways. When adjusted for annual rainfall, the documents show the City has achieved about a 21% improvement from a decade ago.

The fine print is that they are meeting their mandated targets, but their mandated targets have nothing to do with the actual volume of overflows.”

— Nick Pagon, Clean Water Advocate

But, others question the targets themselves and whether the City is relying too heavily on green infrastructure. By design, the City primarily tracks success through modeling, tied to baseline weather conditions of 2006. Nick Pagon, a former Philadelphia School District teacher who became a clean water advocate after starting a boat-building nonprofit for kids in the city, believes the approach is already obsolete due to climate change, which is increasing the number of extreme rainfall events that exacerbate sewage overflows.

“The fine print is that they are meeting their mandated targets, but their mandated targets have nothing to do with the actual volume of overflows,” Pagon says.

The nonprofit PennEnvironment shares his concerns. This summer, the group released a detailed report on Philadelphia’s sewer overflows. While PWD’s documents estimate that Green City, Clean Waters has so far reduced three billion gallons of overflows during a typical year, the PennEnvironment report points out that Philadelphia still releases much more: according to the city’s records, it’s released anywhere from nine to 16 billion gallons annually over the past half decade. In 2022, PennEnvironment calculated, such overflows made portions of the Schuylkill unsafe for recreation for 162 days, and for the Tacony, 128 days.

John Rumpler, clean water director and senior attorney for Environment America, says the nonprofit sees the value of green infrastructure, but still believes the City needs to rethink its overall strategy, especially in light of climate change.

“Even though they’ve made progress, they’re falling short because there’s increased rainfall,” Rumpler says.

There are also questions about the long-term chances of success. To meet its overall goals, the city must create 9,500 acres of new green infrastructure by 2035. That’s more land area than the Wissahickon Valley, Pennypack, FDR and Fairmount parks combined. By taking the total acreage of improvements so far and extrapolating to 2035 based on recent annual averages, our reporting found, the City is on pace to reach only 60% of its target.

The PWD did not offer responses to a reporter’s questions for this story within a two-week deadline. A spokesperson said the department would need one to two months, but did provide links to relevant documents.

Still, there’s an even more complicated, third perspective. Laura Toran, a hydrogeologist and professor at Temple University, is among a handful of local environmental experts with firsthand experience studying the effectiveness of green infrastructure. On the whole, Toran says, it performs well for its primary purpose of keeping stormwater out of sewers, and thus sewage out of rivers. She adds there are indeed still thorny questions, such as to exactly what extent green infrastructure works, whether it captures runoff pollution like road salt, and whether there is ultimately enough “greenable” space in the city to complete the Green City, Clean Waters plan.

For Toran though, these questions miss the bigger picture. Echoed by other professionals in the space, she’s seen the range of solutions any city can implement to deal with stormwater, and thinks whatever the shortfalls of green infrastructure may be, it’s worth prioritizing over the expensive, concrete ways of the past. In places like Europe and China, she notes, engineers acknowledge the approach can get swallowed up by major deluges, but are still doubling down as they endeavor to create a new paradigm.

… you need to do it anyway or else things will get worse. I think that’s a really hard thing for the public to swallow.”

— Laura Toran, Hydrogeologist, Temple University

“It’s very complex, measuring success,” Toran says. “I was fascinated that [overseas experts] admitted that it’s not entirely successful, but you need to do it anyway or else things will get worse. I think that’s a really hard thing for the public to swallow.”

Asked about the EPA’s current opinion of Green City, Clean Waters, an agency spokesperson pointed out the City has met its targets thus far and said the agency routinely communicates with the City and DEP.

“EPA continues to have … discussions with PADEP and PWD regarding any challenges that may require PWD to re-evaluate their program,” the spokesperson said.

When asked if the DEP has expressed any concerns about the program’s performance, a spokesperson simply responded, “No.”

If the agencies determine at any point that the program is falling short, they have authority to put new screws to the City. But the stakes are perhaps highest for Philadelphians, from the everyday taxpayer paying for the program, to those like Roy who look out over still-polluted waters and wonder if more can be done.

“To me, it’s really unfinished business,” Roy says. “It’s a long-term issue, but we can’t lose sight of it.”

Germantown, underwater

When Leem Patton, 19, and his family moved from West Philly to adjacent townhomes in Germantown three years ago, they had no idea they were moving onto a street so flood prone that people sometimes have to swim from their cars to their front doors.

After moving in, one of their new neighbors gave them a heads up that the block floods. But they’d learn firsthand soon enough. On July 6, 2020, Patton’s sister posted a video shot from her porch looking down at the intersection of Church Lane and Belfield Avenue below. Severe thunderstorms were passing through Philadelphia and floodwaters had completely submerged the intersection. They were now pushing several feet up the front steps of the home.

In the video, a red pickup truck plows through the water. Going the other way a minivan pushes a sedan, which appears to be stuck or disabled. Off camera, a neighbor yells, “We used to this s***!”

Patton says three years later, the family is in some ways used to it. Floods happen frequently and one totaled his mom’s car. Now they know to move their vehicles to a higher elevation when a good rain is on the way. Still, it’s stressful.

“We think about it a lot, every time it rains bad,” Patton says.

Patton and his family aren’t alone. Flooding is a recurrent problem in Germantown and parts of Mount Airy. During Hurricane Irene in 2011, Deanna Compton, a 27-year-old mother of one, was driving home late at night when her vehicle became stuck in floodwaters at the intersection of Haines Street and Belfield Avenue, resulting in her death by drowning. Two years later, area residents told ABC6 they were fed up with flooding and basement sewage backups, which can occur when sewer mains are so filled with sewage and stormwater they can force the mixture back up into homes.

Retired environmental engineer Kelly O’Day thinks more can be done to help them. The East Mount Airy resident is something like a low-key crusader for green issues in the city, particularly sewers and plastic pollution.

It’s the grossest outfall in the region …T1 is like the hidden secret of the grossness of the combined sewer overflows.”

— Kelly O’Day, Environmental Engineer

“It’s the grossest outfall in the region,” O’Day says. “It takes a [big] drainage area of Philadelphia and discharges it into this tiny little creek. T1 is like the hidden secret of the grossness of the combined sewer overflows.”

O’Day does think green infrastructure can help to cut down on sewer overflows. But, he says, it has its limits and believes more traditional infrastructure is still needed to solve acute problems like those in Germantown.

For proof, O’Day points to a map with red dots marking the street intersections that repeatedly flood within the Wingohocking watershed. These choke points primarily fall in more upstream areas in Germantown, not lower-lying areas like Logan and Wayne Junction where one might expect. That’s because, O’Day says, in the mid-20th century Philadelphia performed a massive expansion of the sewer lines running west from the Frankford, but stopped short of redoing the entire watershed in the 1980s.

“They may not have had the money to upgrade the upper Wingohocking,” O’Day says. “Up to the edge of the red dots.”

O’Day says he knows costs remain a limiting factor for PWD’s operations. But he says green infrastructure isn’t solving the pressing problems in Germantown — the City itself estimates $8.72 million in property damages a year— and time is being lost.

In its original 2011 planning document for Green City, Clean Waters, PWD estimated about $2.4 billion in investments under the plan citywide. The lionshare, about $1.7 billion, would go to green infrastructure. But it would also spend hundreds of millions of dollars to upgrade its three wastewater plants to handle more sewage and reline pipes to keep sewage out of the Tacony and Cobbs creeks. And, it would set aside $420 million in a “flexible” spending category for green or concrete infrastructure, “whichever proves more efficient as the program evolves.”

In a response to the PennEnvironment sewer report this year, PWD said it is committed to spending “over $4.5 billion in capital program infrastructure investments,” through 2029, with $1 billion dedicated to combined sewers.

The water department has also not been absentee in Germantown. Emaleigh Doley, executive director of the Germantown United Community Development Corporation, says PWD has been “doing a lot of work” in the area, including installing green infrastructure and meeting with community members. She thinks it’s a bigger problem than PWD can solve alone, as there are also concerns about the affordability of flood insurance, the lack of disclosures of flood risk during real estate transactions and whether some homes should have been built in what amounts to an unmarked flood zone in the first place.

“It’s a big enough problem that it’s not going to have any easy solutions,” Doley says.

Indeed, PWD has studied the Germantown flooding problem and in 2019 released a report laying out potential solutions. It calculated that more traditional infrastructure options, such as a series of underground storage basins or a five-mile long storage tunnel running under Chew Avenue, could reduce flood depths by as much as 80% and eliminate up to two-thirds of basement backups. But estimated costs for the projects ranged from $384 to $585 million, which would eat up the entirety of the City’s flexible budget under Green City, Clean Waters.

PWD did not respond by deadline to a question about the status of its plans in Germantown, but did provide a copy of a December 2022 RFP seeking “the first level of conceptual design for the Wingohocking Relief Sewer Tunnel, which extends from the flood prone areas in Germantown to the Tacony Creek.”

For Howard Neukrug, a former commissioner of PWD who spearheaded the creation of Green City, Clean Waters, money is the defining, inescapable factor. As the City was evaluating its options while creating the program, he says PWD did look at more traditional options citywide, such as digging massive underground tunnels. Cities like Chicago and Washington, D.C. have spent billions of dollars on such projects, successfully storing hundreds of millions of gallons of sewage-laden stormwater during deluges, then pumping it back to the surface for treatment during drier days.

All the tunnels have nicknames. Ours was ‘the 100-year-tunnel.’ That’s how long it would take for us to be able to, in a city like Philadelphia, find the $10 billion dollars, put it in the rate structure, and have people pay for this thing.”

— Howard Neukrug, former PWD Commissioner

But in Philadelphia, those options had a price tag that would likely approach $10 billion in today’s dollars, Neukrug says, several-fold more than the green infrastructure approach. Going down that path would have added sharply to affordability concerns in a city where residents are already facing annual double-digit rate increases on their water bills and have a history of delinquency.

“All the tunnels have nicknames. Ours was ‘the 100-year-tunnel,’” Neukrug says. “That’s how long it would take for us to be able to, in a city like Philadelphia, find the $10 billion dollars, put it in the rate structure, and have people pay for this thing.”

Building large tunnels, Neukrug adds, can also greatly disrupt urban life during their construction, require heavy energy usage to operate, come with none of the co-benefits of green infrastructure, and also become susceptible to obsolescence wrought by climate change.

“You look at the green infrastructure solution, and you say, ‘While you’re designing the tunnel, we’re planting trees,’” Neukrug says. “We get benefits from day one.”

But Pagon, the former boatbuilder-turned-water advocate, doesn’t believe that Philadelphia is doing the best it can. He says one need look no further than just across the Delaware, to Camden.

A tale of two cities

When discussions began about a decade ago between the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Camden about its own combined sewer problems, Andy Kricun, then executive director of the Camden County Municipal Utilities Authority (MUA), says there was a great blueprint to follow: Philadelphia’s Green City, Clean Waters, which was formalized just a few years earlier.

“When [the program] first came out, it was groundbreaking,” Kricun says, “Nobody had been thinking about this idea … it was really smart, a game changer.”

Kricun reached out to Neukrug and others at PWD to learn about their approach and says, in many ways, the Camden MUA — responsible for handling and treating sewage from all of Camden County — copied it.

But there were a few key differences.

Most significant was how Camden measured success. In Philadelphia, the primary metric is the installation of “Greened Acres.” It’s essentially a modeling exercise, where each piece of green infrastructure is designed to capture a certain amount of stormwater. Install enough acres, the model shows, and the city will have reduced sewage overflows by an amount acceptable to regulators.

Camden, Kricun says, prioritized eliminating sewage flooding in homes as well as combined sewage overflows into the river, measured by devices that detect actual overflows from the sewers.

“In order to do that, we looked at gray [traditional] infrastructure improvements as the centerpiece of our program with green infrastructure being a complementary feature,” Kricun says. “PWD’s is the reverse — green infrastructure is the centerpiece, complemented by gray infrastructure.”

Camden also put nets on the end of all of their overflow pipes to capture sewage sludge as well as floating plastics with sensors that indicate when they’ve been impacted. Each of these goals came with hard data or dependable community feedback to indicate they were working.

For these reasons, some advocates on the Pennsylvania side of the river like Pagon hold up Camden’s approach as superior.

“Camden is doing much better for a variety of reasons,” Pagon says.

Kricun doesn’t go that far. Philadelphia is a different beast, he points out, much larger in size and thus more costly to fix.

“The Green City, Clean Waters plan has already done a great deal of good for water quality in the Philadelphia region and will be even more beneficial when it has been completed,” Kricun says.

Experts like Toran, the Temple University hydrogeologist, also caution that perceived improvements — like placing nets over pipes — can have significant maintenance issues and costs. In Philadelphia, there are over 160 sewer outfalls, compared to 28 in Camden, and many are in potentially tricky locations to maintain, like the Delaware River.

Yet in interviews, even experts supportive of Green City, Clean Waters cautiously suggest close inspection. For Kricun, a pertinent question is whether Philadelphia’s use of 2006 as a baseline for its models will hold up, as climate scientists predict continued increases in extreme rainfall. He also has equity concerns. In Camden, green infrastructure installation was prioritized in frequently flooded environmental justice communities. But Philadelphia views installation at any location equally.

“[Green City, Clean Waters] could be improved upon to address climate change, incorporate equity considerations and achieve even better water quality outcomes,” Kricun says.

There’s also the question of whether or not there’s even enough room to put nearly 10,000 green acres in Philadelphia. Under their 25-year agreement with regulators, installation is weighted toward the tail end. Philadelphia hit its target of about 2,100 acres at the ten-year mark, but that left 7,400 to go. And over the past half decade, PWD has averaged only 236 new acres a year. At that rate, Philadelphia would install about 5,700 acres by 2035, less than 60% of the total target.

“We have a major city with thousands of acres of impervious surface, so to implement and make this work, you need a lot of green,” says Robert Traver, an environmental engineer and Director of Villanova University’s Center for Resilient Water Systems.

For some, these issues prompt serious questions about the program at its halfway mark. With the city spending billions on a program that may not be working, waiting another decade amounts to lost time and taxpayer money. Rumpler, of Environment America, says the program’s stated $2.4 billion price tag is probably even too low, and that state and federal lawmakers — along with suburban communities that send sewage to Philadelphia for treatment — should all be contributing more money to help pay for it.

“I think it’s a mistake to start debating how much of that $2.4 billion should be green and how much should be [traditional] infrastructure,” Rumpler says. “It wouldn’t surprise me if they need to just double that number, at a minimum, to get to the point where they’re really dramatically ratcheting down and ideally eliminating their sewage overflows.”

But Neukrug says many of these criticisms miss a bigger picture. The Philadelphia Water Department is an extremely forward-looking organization, he says. There is a century of unprecedented challenges ahead. With climate change bearing down and sea levels rising, saltwater intrusion could potentially threaten the very safety of the city’s drinking water and require extremely expensive upgrades to fix. Residents of the heavily impoverished city already face affordability problems across the board. Constantly lurking are the threats of unregulated chemicals and lead pipes.

In other words, Philadelphia has a lot on its plate and limited dollars to go around.

From this perspective, Green City, Clean Waters is the right tool: an innovative and relatively low-cost solution that returns value to the community in more ways than one. Neukrug says although its exact effectiveness can be tough to pin down, that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned at halftime. It has too much merit, he argues, and the water department can do more in 2035 if it finds progress isn’t sufficient.

“It’s hard to say who is wrong or right either way,” Neukrug says. “[But] we’re supporting the growth of a sustainable city … and that’s it, that’s the spot. That’s environmental justice, fairness and affordability.”

[…] jumped at a chance to team up with Grid and support my most intensive freelance reporting to date, looking into a multi-billion dollar city sewer program. Friendly collaboration in journalism, how truly […]