On an April morning the heat soars into the realm of summer as a runner cruises back and forth along a paved path. A pair of chatting college students overtakes a man walking a spotted dog. And beyond the green borders, urban sounds from sirens and passing trolleys fade as birdsong rises through the trees. The Woodlands, a cemetery that is home to gardens, graves and wildlife and the former estate of amateur botanist William Hamilton (1745–1813), invites the living to come in, slow down and breathe.

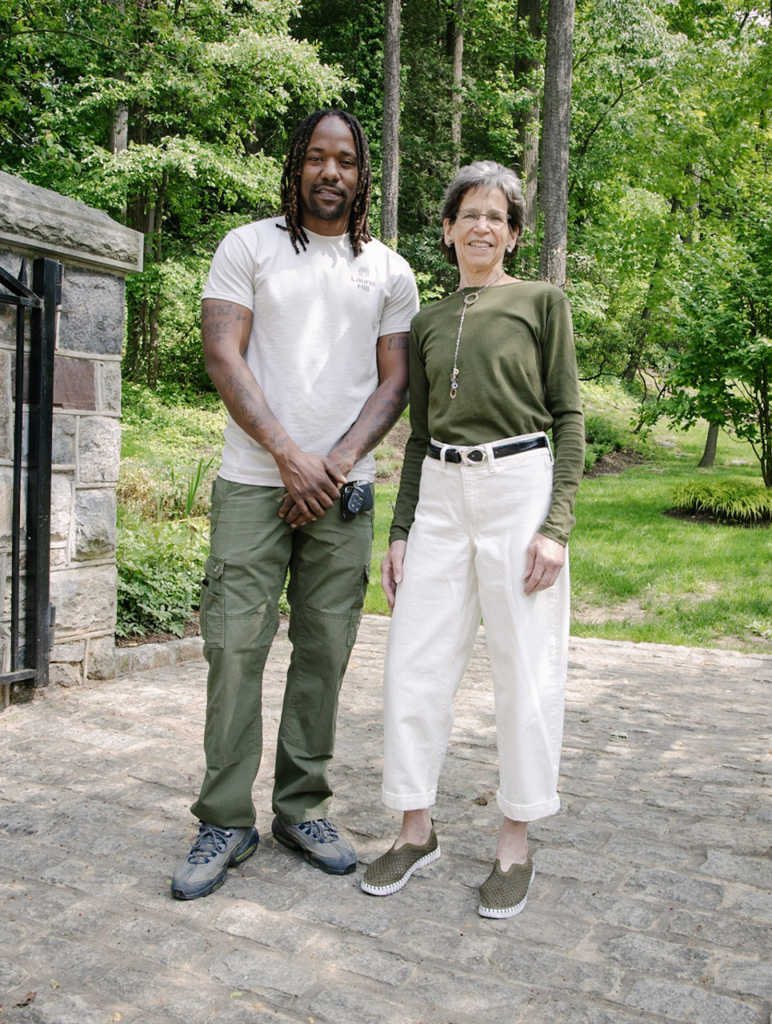

Emma Max, public programs and operations manager, says that staff works to create a balance between offering a welcoming space to the community and honoring the needs of those seeking a quiet, contemplative space for grief and reflection. Burials take place in a space apart from what Max calls the “historic Hamilton core,” which is used for public events. “We are a Victorian era cemetery, and there’s a history of people spending leisure time in cemeteries and picnicking and being happy here,” she says.

In the early days the land took shape after Hamilton, who inherited the estate in 1767, made it his life’s work to develop the property to rival reigning English fashion of the time. After Hamilton’s death, however, family members sold off bits of the land until The Woodlands Cemetery Company acquired what was left in 1840. According to the website, the company’s goal was to protect the remaining land as a “rural cemetery.”

Today, 54 acres remain of the original 600-acre estate; the parcel has been preserved as a National Historic Landmark District since 1967. The Woodlands maintains an active cemetery business, selling up to 30 plots per year for burials and cremations. Visitors make use of paved carriage paths throughout and wheelchair-accessible bathrooms. For public events, staff uses temporary ramps for the mansion steps.

Trees and other plants grow throughout the grounds, which provide a home to pollinators and animals that visitors might not expect: foxes, resident hawks and migratory birds that use the space as a stopover point. “Keeping as much of a habitat that can sustain those creatures is something that we really are proud to be able to do,” Max says. “You can step in through the gates and be surrounded by nature. We strive to make The Woodlands a hub for nature and for people who have difficulty accessing it in other ways,” Max says as she points out the trolley stop across the street.

A corps of 150 volunteer gardeners, supported by Robin Rick, facilities and landscape manager, maintains the habitat and continues the landscaping traditions started by Hamilton. Before new gardeners put a hand to the soil, they take part in training sessions to learn about plant maintenance, historic preservation and Victorian gardening. Today many visitors come in the spring to see the extravagant blooms nestled in Victorian cradle graves. Iris varietals thrive throughout the grounds, some dating back to the early 1900s. The oldest tree, a damaged hedge maple, may have been planted by Hamilton himself. “It’s a symbol of resilience,” Max says.

Families love to plant trees, but people often don’t think 100 years in the future.”

– Emma Max, The Woodlands

The Woodlands wasn’t always like this. Jessica Baumert, The Woodlands executive director, came on board in 2011 with a background in historic preservation. She lives in the neighborhood, and, prior to taking the position, she would visit to go running. She describes it as mowed and tidy at that time but without many visitors. “It clearly was not meeting its full potential,” she says.

Now on a nice day “there’s a constant flow of people in and out,” Baumert says. She attributes much of this activity to the expanded public programming. In the past two years staff has worked with 15 other community organizations. The Philadelphia Orchard Project, for example, has a learning orchard and bee hives on the grounds and educates visitors about plant and tree care. They open their orchard during the Nature Night series; they hold plant sales and volunteer work days.

Naomi Segal and Rie Brosco came out to admire the flowering azaleas recently. “It’s thrilling to see,” Segal says.

The pair live in the neighborhood and have friends who are buried at The Woodlands, but Brosco says that the programming for the living is one of her favorite things about the cemetery. “It’s about all sorts of people coming and enjoying the natural beauty.”

Many famous folk are buried at the cemetery, including painter Thomas Eakins and his subject in “The Gross Clinic,” Dr. Samuel D. Gross. On a walk through the grounds, Max counsels that it’s okay to step over the graves, but one must do it with respect. She pauses to point out a tombstone that reads only “Cornelia.” A soft olive lichen covers much of it, but there’s no date to obscure. “It’s nice when a stone is a bit of a mystery,” she says.

Despite the help from outside partners, The Woodlands staff has a wish list of things they would like to implement. Baumert explains that many people believe the City contributes funding, but the private cemetery’s funding comes from the cemetery business, grants and donations, which can make it a struggle to meet visitors’ needs. And annual visitorship doubled from 75,000 pre-pandemic to 150,000. Post-pandemic those numbers have remained steady. “We would like to have the bathrooms open on the weekends,” Baumert says, “but there isn’t funding for it.”

Fallen tombstones are another challenge, and visitors notice them. Staff relies on interns from the University of Pennsylvania’s Historic Preservation Department, another community partner, to help, but it takes time. No one likes to see the fallen stones, Max says, but the work involves stabilizing and leveling the ground, so “they’re safer on the ground. Once we’re able to get the equipment in, we will reset [as many as] 50 stones.”

On a recent walk, Max points out a favorite tree, a towering London planetree that has overgrown its plot and incorporated a small border structure into its root system. “Families love to plant trees,” Max says, “but people often don’t think 100 years in the future.”

Although the community that has come to rely on The Woodlands may not be thinking far into the future, they can rest assured that someone is. “We are the caretakers of people,” Max says. “We hold that responsibility higher above all else … We know, more than many people, that everyone dies eventually, and that life is really precious. But death is also a part of life.”