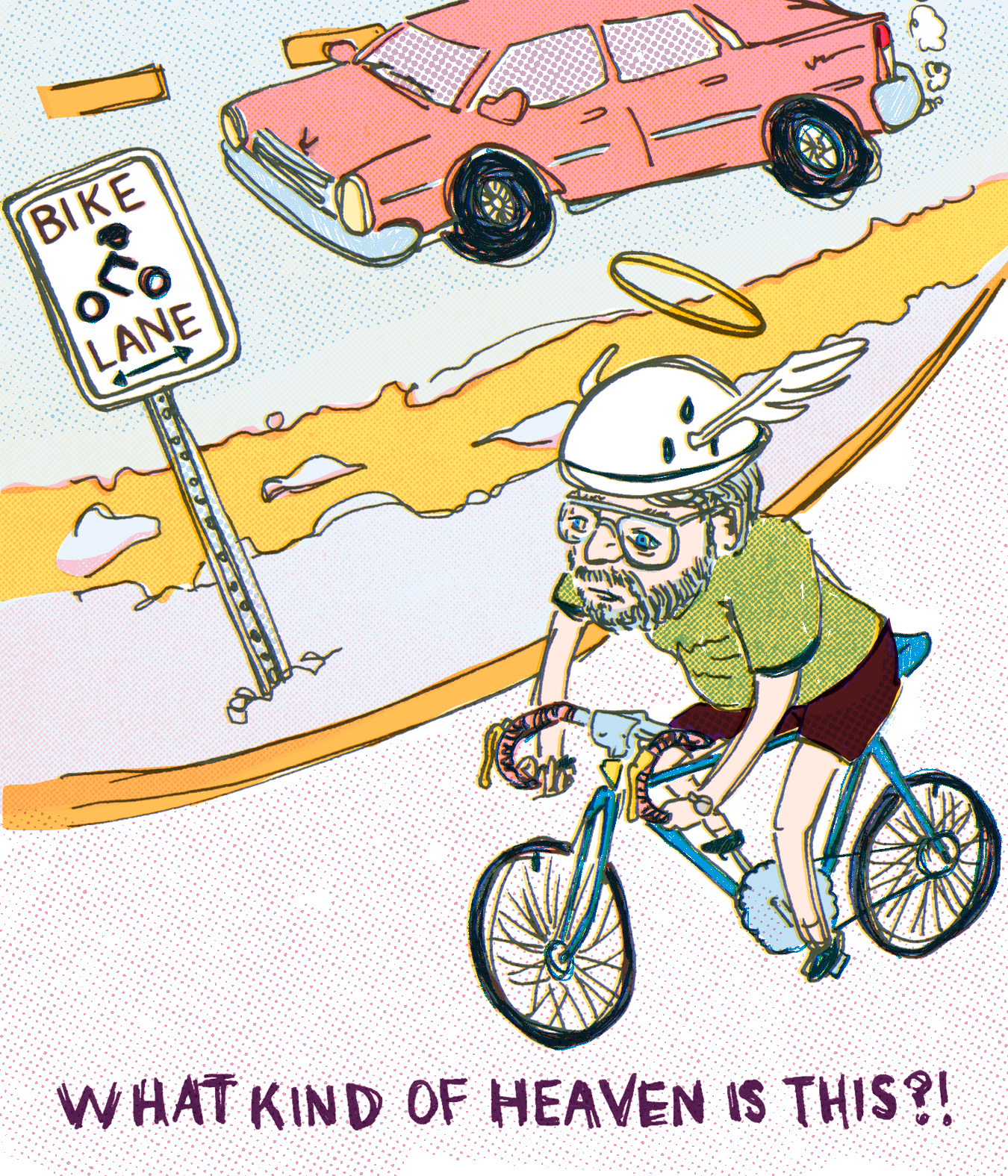

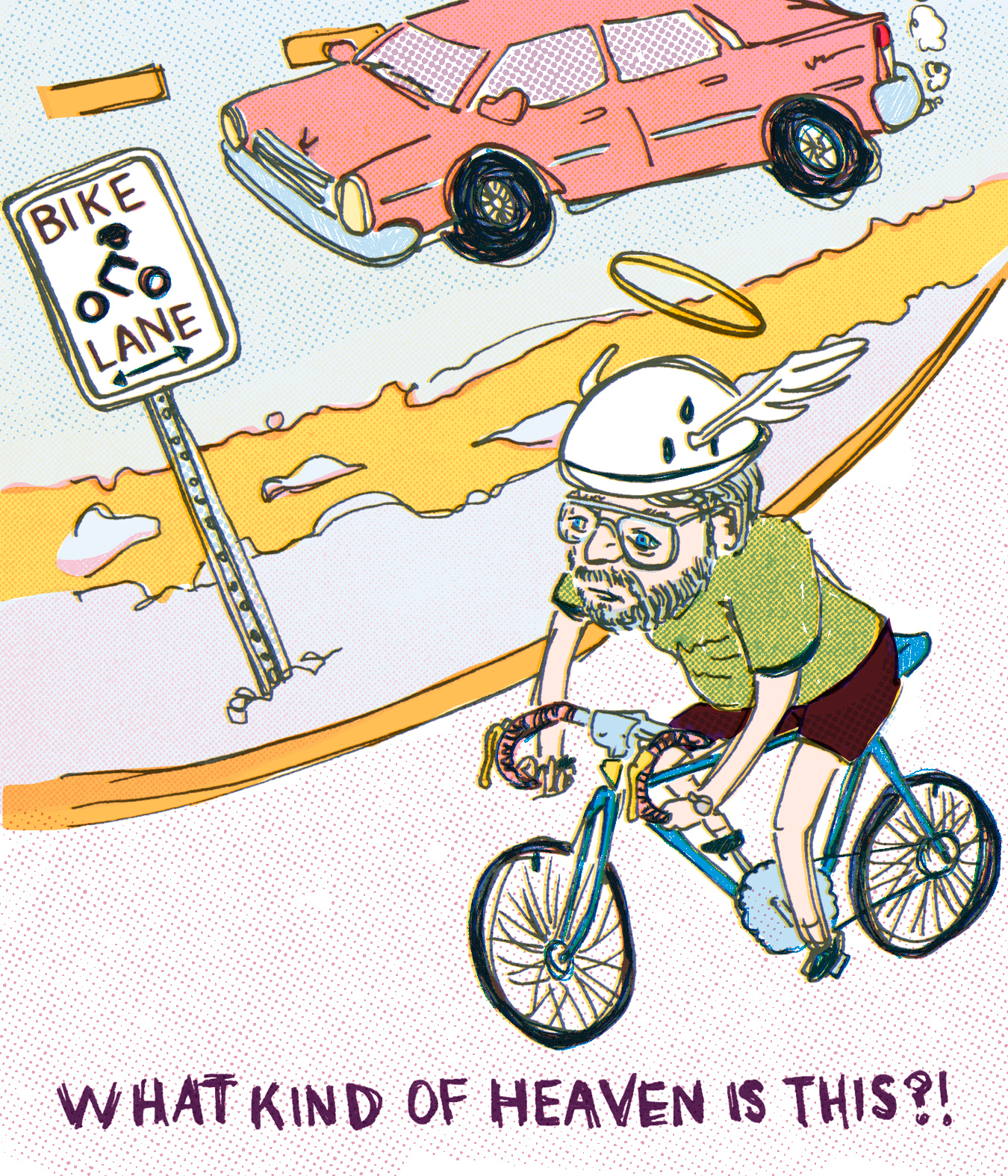

Illustration By Sean Rynkewicz

Middle of the Road

Story By Randy LoBasso

You might not be familiar with the work of the late John Forester, but if you ride a bicycle, he’s had a huge impact on your safety and the way you interact with the roadway.

The godfather of “vehicular cycling,” Forester promoted the idea that cyclists should use the road just like any other legal vehicle, and that bike paths—paved paths designed specifically for bicycles—are dangerous and should be outlawed.

Forester died in April, at age 90, but his legacy lives on.

Every time you ride your bike on a street and get honked at by a driver trying to pass you, that’s Forester’s work in action. Why? Because perhaps the most influential bicycle advocate over the past 50 years wasn’t much of an advocate at all. His 1973 work Effective Cycling promoted the idea that bicycling should be an activity only utilized by the few.

Over the past decade, a great deal of criticism has gone Forester’s way over his idea that riding a bike in traffic is the safest possible way to ride a bike. His research is now considered obsolete—a few decades too late.

I’m not a fan of Forester’s work, but I find that something important is often lost in critiques: his never-ending fight against the supremacy of the automobile.

The way he saw it, protected bike lanes and bike paths were the government-funded

admission that cyclists had lost to the car—and he was onto something there.

Forester’s cycling story begins in Palo Alto, California, where, in the early 1970s, a bikeway—or bike highway—was built and a law was changed to force cyclists to use the off-street path instead of the street. An early advocate of biking in traffic, Forester staged a one-man protest in his adopted hometown, cycling in the middle of the street in front of a police officer and receiving a summons. He then began his career advocating against both Dutch-style cycle tracks (what we think of as raised, protected bike lanes) and the cultural and physical dominance of motor vehicles.

A year after his summons, he began writing the book on, and teaching and promoting, his vehicular cycling techniques. Forester maintained that, in addition to being less safe than riding with motorists, separated bike paths would lead to novice cycling in cities and towns, creating a situation in which cyclists who want to ride fast in the street could not. As Forester’s book gained steam, his theories about vehicular cycling helped stop the promotion of separated bikeways in the United States, even as European cities saw bicycling grow with the promotion of off-street bikeways.

While bicycling groups have promoted cycling as a means for anyone to get wherever they want to go, Forester did not envision bicycle transportation becoming mainstream and widely used. Bicycling is a “minority activity and I didn’t expect it to be any more than that because I knew the difficulty,” he once told a reporter for Momentum Mag.

Rutgers University Urban Planning and Policy Development Program and Research Associate John Pucher once noted, “the most far-reaching impact of Forester’s philosophy was getting an effective ban on separated paths written into the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Guide for the Development of Bicycling Facilities [which] was changed to denounce separated path treatments.”

This libertarian philosophy to road design has kept American roadways from realizing their full potential as safe places to ride bicycles and has led to the rise of both the motor vehicle and fossil fuel industries. Even the densest, flattest cities in the United States are jammed with motor vehicles, polluting our air and parking in pedestrians’ and bicyclists’ rights of way without consequence.

It’s important to note that that wasn’t Forester’s intention.

Throughout his life, he ceded no ground, whatsoever, to car culture. His idea remained, until his death, that if you separate motor vehicles and bicycles, motorists will have free reign to do whatever they want, with little consequence.

“The bikeway system was devised by motorists to provide the physical enforcement of these laws that, motorists think, make bicycling safe by keeping ‘their’ roads clear of bicycles,” Forester’s website claims. “The environmentalists were suckered into this bogus safety argument and now demand bikeways to make bicycle transportation safe and popular. With the government spending more and more money on bikeway programs, lawful and competent cyclists are being more and more limited to operating on bikeways that are unsuitable for lawful and competent cycling.”

In his death, I give him this: Politicians regularly propose banning cycling outside of bike lanes, often believing they were the first to come up with the idea. Bicycle advocates too regularly have to fight back against governments that propose forcing bicyclists into protected bike lanes. From my experience, bicycles in traffic are seen as a nuisance to motorists, and bike paths are seen as a detrimental sacrifice of vehicle parking.

Protected bike lanes are proposed all the time, but local governments provide little to no funding for them, and advocates are too often forced to beg for small sections of protected bike lanes that have little chance of being built if opposed by people who live on the block where the path will be constructed. And, even if they are constructed, chances are nil that they will connect to a greater network of protected lanes. Protected bike lanes are often planned on streets where they will have minimal impact on drivers.

While we think of protected bike lanes as wins in cities—because they are—you’d never see a group of motorists forced to show up at a community meeting and make the point for widening a highway so they didn’t have to sit in traffic. It’s simply a given that highways are going to be built, whether the “near-neighbors” want it or not. A bike lane’s construction, on the other hand, can be (and has been) thwarted by the opposition of a single person.

This, Forester noted, is the end result of relying on governments to build us things we think we need.

“Motorists, for their own convenience, denied cyclists important rights, thus making cyclists second-class road users, trespassers subject to discrimination by police and harassment by motorists, and unable to take advantage of the safety and efficiency of obeying the standard traffic rules,” Forester continued on his website.

I don’t subscribe to all of his ideas—but Forester’s philosophy was probably right.