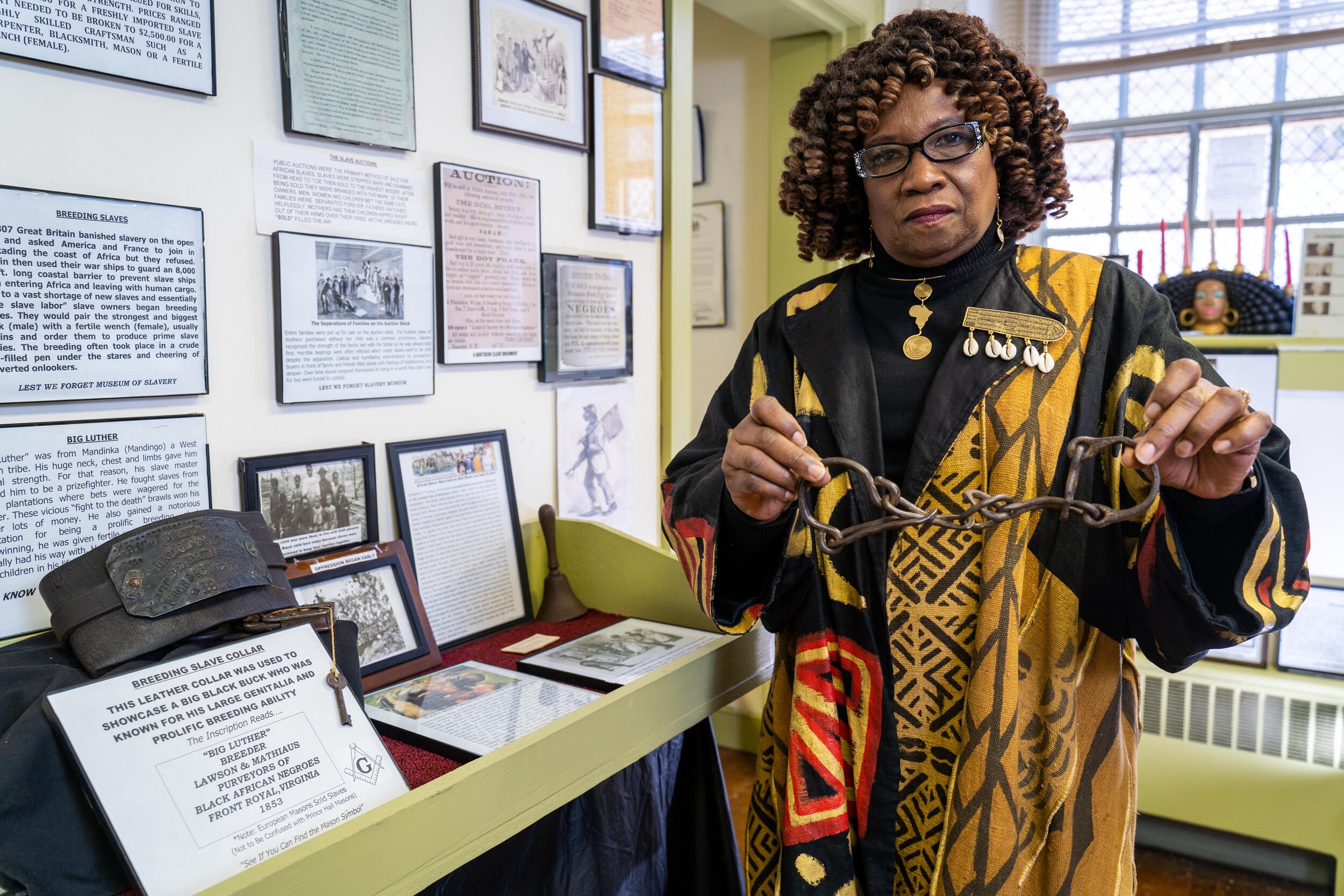

Gwen Ragsdale, co-curator of the Lest We Forget Slavery Museum, holds a piece of ironware that was used to restrain slaves. | Photography by Milton Lindsay

By Constance Garcia-Barrio

Just when I began to sense the significance of the life of my great-grandmother, Rose Wilson Ware, or Maw (1851–1964), she died. Maw and I had 18 years of overlap since I was born in 1946. During the summers of my childhood, my parents, my brother and I would visit Maw’s farm in Partlow, Va., drink cool water from her well, look into her wizened face and hear how Maw’s grandmother, Hannah, stepped off a slave ship in Baltimore, possibly in the late 1790s, and walked with a coffle of other enslaved Africans to Virginia.

I would squeal with delight as my dad, now long dead, pushed me in a wheelbarrow over land that Maw and her husband, Jake, bought with money earned from sharecropping after freedom came.

Even with my trove of memories, much eluded me. I would ask Maw so many questions now: how she “learned her letters,” illegal for enslaved Blacks; what she recalled of the Civil War; how she held on to her farm as a middle-aged widow in the Jim Crow South.

Four hundred years have passed since the frigate White Lion brought enslaved Africans to Jamestown, Va., while more than 156 have gone by since President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Those dates may seem distant, yet slavery still echoes in all levels of life in the U.S. My intimate link with Black bondage through my great-grandmother serves as a reminder that these seemingly far-off eras are only a few generations away.

An elder myself now, I visited some Philadelphia museums to glean what I could about how such institutions discuss slavery’s entanglement in our country’s foundation; and, in so doing, perhaps find answers to some of the questions I would have asked Maw.

The Lest We Forget Slavery Museum displays signs used to segregate establishments and bathrooms based on race. Below: A case holds ironware used to restrain slaves. | Photography by Milton Lindsay

At the African American Museum in Philadelphia, a plump, life-sized Alice of Dunk’s Ferry, aka Black Alice (c.1686–1802), wrung her hands and fretted in a video kiosk.

Said to have arrived on a slave ship as a child, Alice served drinks and oysters in a tavern at age 5, as her master ordered. She lit pipes for patrons like William Penn (1644–1718), who tipped her 1 pence, according to retired Temple University professor of history Susan Klepp.

Later, Alice’s master moved her upriver to what became Bensalem, where she operated a ferry and collected tolls for 40 years. Alice lived her whole life enslaved, Klepp says, but she may have helped other Blacks escape via the ferry. Philadelphians valued Alice as an oral historian who recalled when the city was a tiny town beset by bears and bobcats.

The remaining kiosks and “Audacious Freedom: African Americans in Philadelphia 1776-1876,” the museum’s core exhibit, present African-heritage leaders who fought to end slavery and protect the rights of free Blacks. These stalwarts include millionaire sailmaker James Forten (1766-1842), a Revolutionary War veteran, and one of Forten’s sons-in-law, Robert Purvis (1810-1898), a wealthy businessman of Black and Jewish ancestry, who used his homes in Philadelphia and Byberry (now a neighborhood in Northeast) as stations on the Underground Railroad.

The strength of the museum’s relatively small collection lies in showing, through Black Alice, how William Penn helped to prop up his so-called “Holy Experiment,” the ideal government he established for Pennsylvania, through slavery. The museum also sheds light on the robust activism of Philadelphia’s free Blacks.

I would have had a tot of gin, as Maw did every morning, had I known what awaited me at the Lest We Forget Slavery Museum (LWFSM) in Germantown.

“It’s the only museum of its kind in Philadelphia with authentic slavery artifacts,” says c0-curator Gwen Ragsdale. “We may have the largest collection of slavery ironware in the country.”

Leg irons reminded me of my great-great-grandfather Robert, Maw’s father, who was “… sold South because he wouldn’t let anyone but the master whip him,” according to Maw. He would have worn such restraints when slave traders took him from Belle Air, the Virginia plantation where my family labored.

Photography by Milton Lindsay

LWFSM, a small museum packed with images, information and artifacts, had its start with a legacy.

“My husband used to spend summers with his great-uncle Bub in Rock Hill, South Carolina,” says Ragsdale, whose powerful storytelling brings each item to life. “Uncle Bub would tell him stories about ‘massa’ [master] and slavery. After Uncle Bub died, my husband looked in one of his uncle’s old trunks and found a pair of hand shackles. That’s how it began. Now we have thousands of artifacts.”

Ragsdale emphasizes slavery’s effect on families. “Blacks couldn’t marry, so they developed the tradition of jumping the broom to declare themselves man and wife,” she says. “But they could still be sold away from each other at any time.”

Another factor threatened couples and families. According to Ragsdale, when a law forbade importing Africans after 1808, some masters ordered enslaved men and women to cohabitate in order to produce children.

The LWFSM collection also covers resistance to slavery. The determined look of businessman William Still (1821-1902) suggests the courage that earned him the title Father of the Underground Railroad. Still hid records of Blacks that he had helped escape in a cemetery, one story says, to aid family members in finding each other later.

Ragsdale discusses slavery’s legacy, such as lynching and the present-day killing of Black men by the police. The tour ends on a high note with a look at African American inventors like mathematician Gladys West, who was instrumental in developing GPS.

“We’ve had extreme challenges, and we’ve made huge strides,” Ragsdale says. “The museum is here, lest we forget.”

I entered the Museum of the American Revolution with misgivings.

George Washington (1732–1799), the war’s hero, and his wife, Martha (1731–1802), used slavery to “… build and maintain [Mount Vernon], their [Virginia]… plantation,” according to the historic home’s website. What could one expect?

I got a surprise.

A sign near the main exhibit acknowledges the presence of enslaved Africans and their descendants. Black bondsmen accounted for one in five British Americans in the 1770s, it states.

Two more items pull no punches. A reproduction of a slave ship’s interior shows how captured Africans crossed the Atlantic jam-packed. A copy of a 1769 broadside announcing the sale of “a cargo of ninety-four prime healthy Negroes” suggests their commercial value.

Both the British and colonists viewed enslaved Blacks as potential game-changers, people whose labor could provide an edge. At the same time, American patriots may have been of two minds about acknowledging African Americans, judging by one exhibit. Consider the case of Crispus Attucks (c.1723-1770), described by the owner from whom he fled in 1750 as “… a Molatto [African and Native American] Fellow… 6 Feet two Inches high, his knees nearer together than common…”

By 1770, tensions ran high between the colonists and the British because the latter kept imposing taxes on the colonies. On March 5, 1770, resentment boiled over. Colonists threw stones and snowballs at British troops, who, confused in the melee, responded with musket fire. Crispus Attucks was among the first Bostonians gunned down.

Some of Paul Revere’s engravings of the massacre, like the one reproduced at the museum, left out Attucks’ racial identity by giving him a light complexion. However, in the 1850s, a sign explains, abolitionists insisted on a new image—also on display—that shows Attucks prominently as a man of African descent. Kudos to the museum for pointing out Revere’s omission.

Some exhibits center on African American women. Feisty Elizabeth Freeman, aka Mumbet (c.1744–1829), wanted her freedom after she heard the Declaration of Independence read. When she said so, her owner hit her with a fire shovel. Mumbet promptly asked an abolitionist lawyer to argue her case. She not only won her freedom and 30 shillings in damages, but also set the stage for ending slavery in Massachusetts.

“Sometimes, freedom wore a red coat” is a key exhibit on slavery. It presents the lives of five Virginians who decided whether to seek freedom by fleeing to British forces.

“These stories were meticulously researched and based on authentic documents,” says Philip C. Mead, Ph.D., the museum’s director of curatorial affairs and chief historian. “We took pains with every aspect and used language children can understand.”

Each story engages visitors in a kind of conversation. It presents the person’s life—for instance, that of Eve, who had to choose between remaining enslaved in the Randolph household or trying to reach British lines. The exhibit gives the pros and cons of each choice, then asks visitors what they would do. One can touch a spot on a screen to see what each person decided and the outcome. Eve runs away and is captured, while a teenage boy joins the British army as a trumpeter and later settles in Nova Scotia, far from his family. It takes time to read each story—stools are provided—and it’s worth every minute.

I felt hopeful to not only see slavery included, but notice that people of different races spent time with these exhibits.

Sometimes Freedom Wore a Red Coat is an exhibit at the Museum of the American Revolution that traces the paths of several people from slavery to freedom. | Photography by Milton Lindsay

It was as if a time warp in the driveway zapped me into the 1700s at Stenton in North Philadelphia, home of the brilliant and reputedly crotchety James Logan (1674–1751), in pain from a fall that crippled him at the age of 54. As William Penn’s secretary, a successful fur trader and one-time acting governor of Pennsylvania, Logan became a wealthy man. His home shows it.

An 18th century mansion, Stenton sits on five acres that include outbuildings, a formal garden and a meadow where bees produce delicious honey for sale on-site. Though a Quaker, Logan relied on enslaved and indentured labor.

“Visitors to Stenton can see spaces and passages where enslaved people slept and toiled,” says Dennis Pickeral, Stenton’s executive director. “Many Stenton visitors are surprised that early Pennsylvania Quakers owned slaves.”

Slavery put Stenton in the news several times. The Pennsylvania Gazette of September 1, 1737, carried a story by Benjamin Franklin about Sampson, a Black bondsman who’d escaped from Stenton and was accused later of burning down one of its outbuildings. Caught and convicted, Sampson was condemned to death, but the sentence was commuted to banishment from the British empire. Sampson’s fate remains unknown.

At the other extreme stands Dinah (c.1728–c.1803), the once-enslaved housekeeper at Stenton. Freed by the Logans in 1776 at her request, Dinah and her quick wit became news, and later, a legend.

It seems that after the British trounced Americans in the 1777 Battle of Germantown, a pair of British soldiers knocked on Stenton’s door and told Dinah they meant to burn down the house. They asked Dinah, home alone, for fuel for the fire. She sent them to the barn for straw. While they gathered it, British officers rode up and asked Dinah if she’d seen deserters.

“Yes,” she reportedly said. “There’s two in the barn.”

The officers arrested the soldiers, the story goes, and Stenton was saved.

Recently, newspapers have carried stories of how a 1912 plaque at Stenton honors Dinah as “… the faithful colored caretaker.” Germantown artist Karyn Olivier has developed a new memorial that invites visitors to see Dinah not merely as a servant, but a whole person.

On a tour of Stenton, I saw two chairs that Dinah could have dusted and dishes she probably washed. Though Maw and Dinah lived in different eras, I imagine that, as house servants concerned with textiles—a treasure in colonial America and a necessity for Maw’s dressmaking—they would have understood each other.

Tours have long noted the Logans’ ownership of enslaved Blacks, but the tours are being revamped to deepen that understanding, Pickeral says. There’s also a focus on informing children.

“When fourth and fifth graders visit the site as part of our History Hunters Youth Reporter Program, they learn about slavery’s impact in every room of the house,” he explains.

I attended the 2019 Mid-Atlantic Plantations Conference in October, which put Stenton and slavery in the news again. At the end of the three-day conference, attendees could join a sleepover and spend time in the parts of Stenton most familiar to enslaved people.

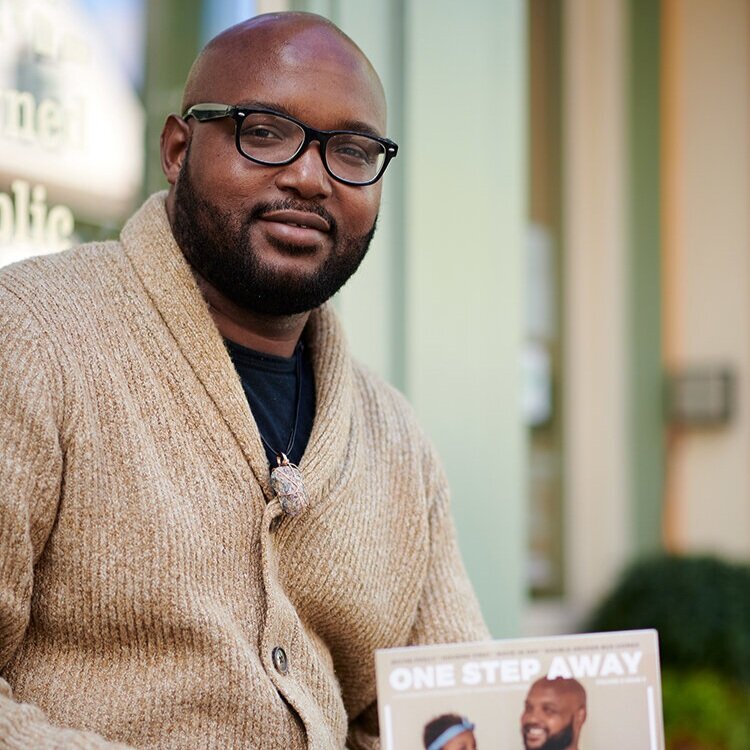

“I lead sleepovers at historic houses to remind people of who built them,” says Joseph McGill, Jr., of Ladson, S.C., founder of the Slave Dwelling Project. “It gives voice to our ancestors.”

Fourteen of us, mostly historians, including two from Europe, spent the night. The adventure drew me in because it held the possibility of sharing Maw’s life in another way. I chose to sleep in a child’s room because, as a girl herself before the Civil War, Maw could have slept on the floor in the room of a child she served.

I lay down on the floor made of wood hewn by enslaved men and asked Maw, in this ancestor space, to gift me with knowledge about her life.