Photography courtesy of Gen Rollins and Sonia Galiber

By Sonia Galiber

In 2018, soil generation launched our first ever policy campaign in response to a rapid wave of land lost by Black and Brown farmers in Philadelphia. We did extensive research throughout our network to understand how power, money and land decisions flow through the city. We identified the agents that hold the decision-making power and opportunities for accountability, made demands we felt were most urgent and tangible and very publicly claimed the urban agriculture narrative to restore truth to its history.

Urban agriculture goes far beyond the stereotypical hipster organic hobby. The history of urban ag in Philadelphia goes back generations. It is a response to uprooted traditions and an act of self-determination.

When Black folks from the South moved to northern cities during the Great Migration (1916-1970) seeking employment and opportunity, many came from agricultural lineages, with histories spanning from slavery to sharecropping to Black land ownership. When immigrant communities moved to Philadelphia for the same kind of economic opportunity, they brought their foods and traditions with them. Historically, and currently, urban agriculture in Philadelphia stems from Black and immigrant groups growing roots in their new home, looking for work and escaping brutal circumstances.

This practice became even more crucial to the survival of these communities as racist policies and practices exacerbated the political and economic injustices surrounding land. When deindustrialization hit Philadelphia in the 1970s, many factories were shut down or relocated, erasing the very work many people migrated to do. It’s not hard to spot a neglected or shut down industrial landscape in the city today. These are the same landscapes where you’ll find spaces that have been nurtured to not only grow food, but also build community, carry tradition, heal the land and generate equity for the neighborhood.

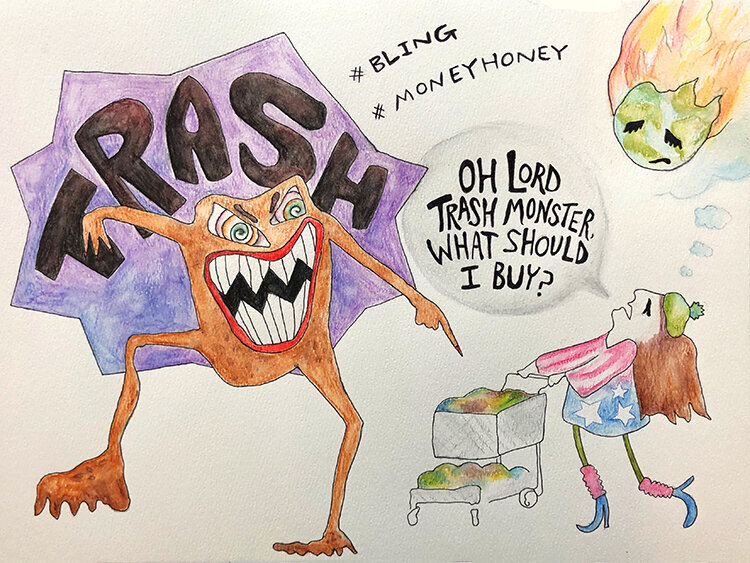

The rapid and displacing development in Philadelphia has destabilized most of our communities’ ability to stay in our homes, provide for our families and pursue the homegrown, self-determined opportunities we’ve created. Land that had often been neglected by the city or the deed holder, but beautified, cared for and utilized and claimed by the people is now back on the market to be sold to the highest bidder. There are now bulldozers and apartment buildings where people of color tended to the land and fed our communities for well over a decade. Some locations have been in operation for much longer.

Champions of development with no regard for community impact often cite the legality of land ownership and entitlement. That perspective does not stand on just grounds when it neglects the impact of land grabbing on human lives. These are the same legal grounds that have institutionalized countless barriers to opportunity for Black and Brown people.

Policy is not the litmus test for what is just. Policy reflects those who write it, enforce it and interpret it. It’s only meant to be accessible to these groups.

Our ecology is changing rapidly. As the people most impacted by environmental and economic injustices, Black and Brown people have already been doing the work of learning to live with the land in ways that policy does not reflect, nor can the status quo address.

Policy, while left to its process, fails to rectify the relationships that will ultimately carry us into a way of life that is as abundant as nature herself. Realizing that policy is one of the apparatuses that stands between us and our vision of culturally rich, healthy, agroecological communities, we fight for threatened gardens, for community control of land, for the land we steward and all the history, labor and love it holds for racial and economic justice. We organize.