By Alexandra Wagner Jone

A powerful little being. That’s how Hannah Caldwell Henderson describes a tiny toddler who stood up during a silent Quaker meeting to say, “Be brave!”

Henderson is the chief advancement officer at Germantown Friends School, a private Quaker school that practices unstructured silent worship.

Much like meditation, silent worship is a personal, contemplative activity. Unlike the traditional Eastern practice, however, that silence can be broken. If someone—and it can be anyone—feels they’ve connected with “an inner truth” or “an inner God,” they speak.

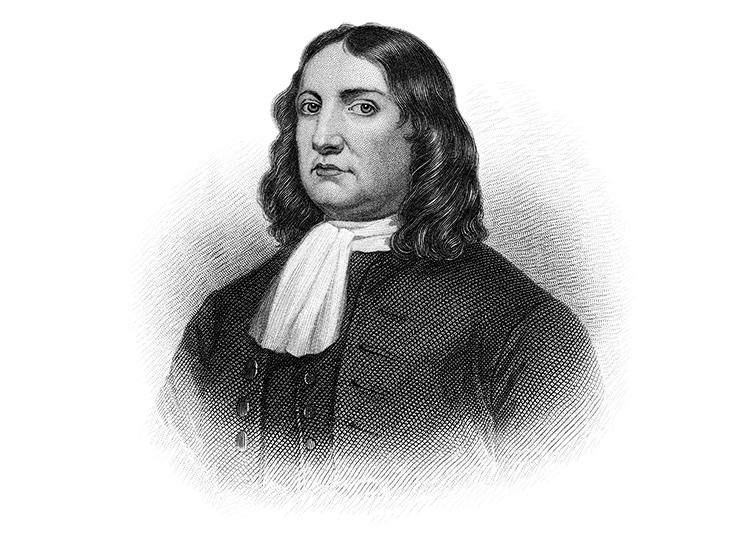

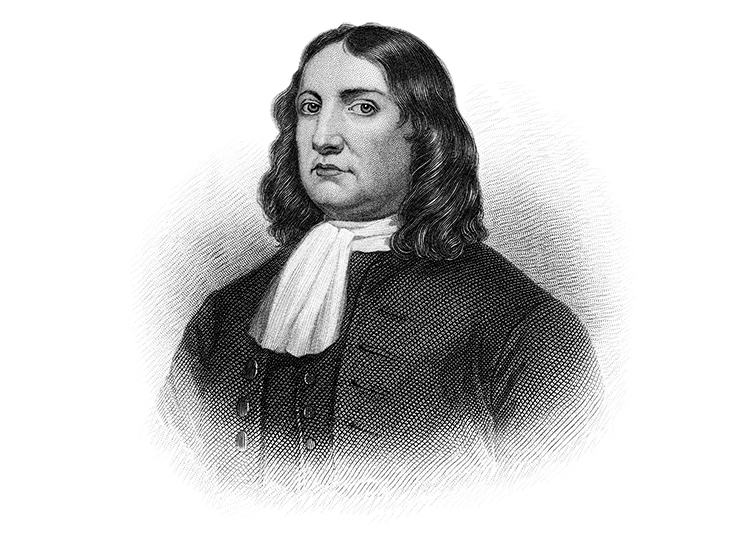

Our state and city’s founder, William Penn, was a firm believer in the practice of silent worship, once saying, “True silence is the rest of the mind; it is to the spirit what sleep is to the body.”

At Germantown Friends, moments of silence seem to crop up everywhere. Classes and faculty meetings begin with them. Sometimes teachers use silence to give students time to reflect in the middle of heated debates or complex lessons.

“It’s a very natural and familiar practice for them,” says Henderson. “They begin to learn, as soon as they hit this campus, their own relationship to silence and how they might use it in ways that create a connection to an inner light or an inner voice.”

Young students are given something to think about in silence for a short period of time—even as little as 30 seconds. As they progress from elementary to middle and high school, students eventually work up to sitting in silence for 45 minutes sessions.

At the Westtown School in West Chester, another school where silent worship is practiced, members of the faculty agree that the practice is powerful. It helps students better connect with both themselves and others in their congregation, they say.

“What is said in that Meeting House is treated differently than anything else that is said on this campus,” says Betsy Swan, co-clerk of Westtown School’s Spiritual Life Committee. “Teaching them how to handle being entrusted with someone’s deepest thoughts changes them dramatically.”

“It’s a test of courage of standing up to speak,” a Westtown School sixth grader wrote about speaking during silent worship, “of listening, of staying still, of being respectful when you don’t agree with someone.”

And it may continue to affect them long after they get out of school.

Nathan Anderson-Stahl, a 24-year-old Quaker living in Philadelphia, says the practice continues to help him to understand others in his congregation. There have been countless times where others’ messages have taught him something or given him a new perspective.

“It’s a place for you to share your concerns, your joys,” he says, “the things in the world that matter to you.”

Along with the benefits of "worship in the manner of Friends" articulated in this article, there is another which I have found important: the ability to utilize this distinctive form of reflection to process times of tragedy or concern.

Students, teachers, and staff who have the discipline of sitting in communal silence with the opportunity to speak openly about "inner promptings" have an invaluable resource when the community has to deal with a difficult situation. When I was a teacher at Friends’ Central School in the ’80s, news of the deaths of two beloved former teachers came to us just before the weekly silent meeting for worship. Everyone knew exactly how to proceed. The school community gathered in silence, and one by one, individuals expressed their sorrow, shared what the two young people had meant to them, offered encouragement and solace, and even told funny stories about their experiences with them. The meeting went on for three hours, with no leadership except "the Spirit" and the community’s own discipline of sitting in silence and attending to "that still, small voice within."

It is a precious resource of Friends schools — often not appreciated fully by students until after graduation or, in the case of Howard’s and Susan’s deaths, when skills are needed to process an event and the unspeakable becomes "speakable."