A place where plants will rule

By Alex Jones

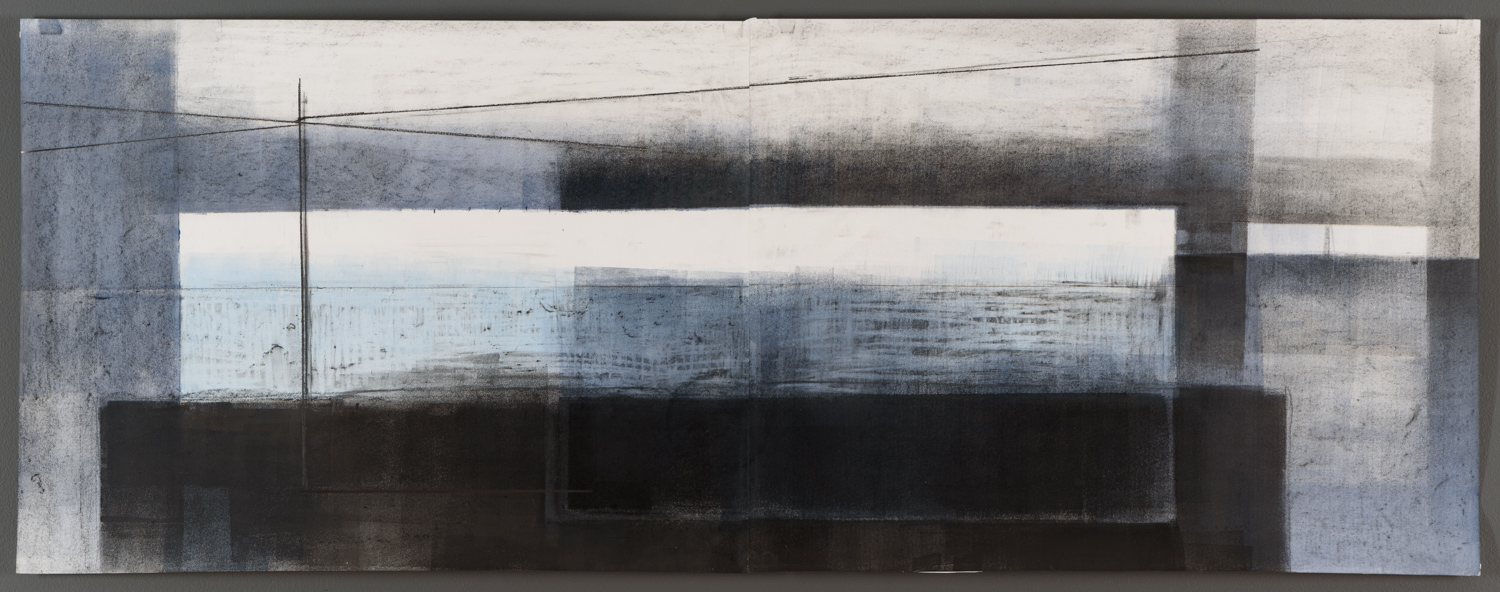

At the region’s newest public garden, you won’t see ruler-straight rows of color-coordinated petunias, or trees pruned into perfect proportions, or hedges of boxwood trimmed high and tight.

At Stoneleigh, native plants get preference, and trees have spent the past century growing wild, unshaped by orchard saws and pruning shears. That’s just what the former owners, the wealthy Haas family, wanted—and Natural Lands Trust, the property’s current steward, will keep it that way.

“One thing the Haases didn’t do is formally prune these trees,” says Ethan Kauffman, Stoneleigh’s executive director. “At other estates, they cut them off like lollipops. But here, they let them grow and twist as they would. It’s a really unorthodox beauty.”

This laissez-faire approach to arboriculture means towering, uniquely gnarled specimens, many more than 100 years old.

An outsized, asymmetrical sycamore welcomes visitors as they approach the property’s main house. The arbor vitae trees that ring the massive, open Circle Garden aren’t the tightly clipped, Christmas-tree-shaped ones you’ve seen edging a suburban lawn—they’re sprawling, multi-trunked specimens, with huge evergreen branches extending along the ground and swooping up dramatically, giving this outdoor space an insular, enclosed feel. Stoneleigh’s massive ironwood, with a damaged trunk that gives it the look of one of the ancient heart trees from “Game of Thrones,” is the largest of its kind in Pennsylvania.

At 42 acres, the Main Line estate-turned-public-garden, which opens to visitors on Mother’s Day weekend, may seem petite compared to the sprawling grounds of Longwood. Its open spaces and knotted trunks may look rather minimalist next to a manicured, perpetually blooming garden such as Chanticleer. But that’s all the better to show off the space’s striking, unique beauty.

“Our style will be very exuberant and romantic,” said Mae Axelrod, director of communications for Natural Lands Trust. “This is a place where plants will rule.”

From titans of industry, to a conservation nonprofit

Stoneleigh’s former owners, John and Chara Haas, lived in the main house, raised a family and took care of the property starting in 1964. John’s father, Otto Haas—one of the founders of chemical company Rohm and Haas—originally purchased it in 1932. While the property was the estate of one of the Main Line’s wealthiest families, John and especially Chara wanted the grounds to reflect the natural world as much as possible, using only native plants and letting long-established trees grow freely and wild.

The site also features examples of historically significant landscape-architecture practices. When United Gas Improvement Co. head Samuel Bodine bought Stoneleigh around the turn of the 20th century, he brought in prestigious Olmstead Brothers firm, owned by the sons of celebrated landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead—they’d bring in plantings, shape pathways and add decorative structures such as lychgates and pergolas around the property for the next 50 years.

Like many other titans of industry in the region, the Haases valued green, natural spaces; John and Chara chose to establish their family home—already something of a nature preserve—as a place where anyone could enjoy the natural world. In 1996, they placed the property under a conservation easement to preserve it in perpetuity; in 2016, their children officially turned the property over to Natural Lands.

“The story of Stoneleigh will be the story of what happens when a land conservancy takes over a garden,” said Axelrod. The organization holds easements on more than 23,000 acres of preserved land in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, from woods to meadow to pastureland. But Stoneleigh is its first public garden.

Natural Lands has spent the past two years readying the property for the public—Kauffman estimates that 70 contractors a day worked on the property during the past 12 months, upgrading facilities and infrastructure—but much of the landscape remains untouched.

Old and new structures, with access in mind

A few small structures have been added, built with local Wissahickon schist; the pool house has been refurbished with a kitchen and restrooms for events. The pool itself has been filled in, but its elliptical shape is outlined in the landscaping, highlighted in grasses with contrasting colors and textures; several circular bogs, a few yards wide, contain moisture-loving carnivorous pitcher plants. Beds that will flank the house were shaped to mimic the asymmetrical angles of the stone used to build the Tudor Revival structure’s walls. (“Curves are boring, everybody does them,” Kauffman explained.)

Stoneleigh also provides a well-preserved example of early 20th century Main Line architecture; at the time, the area was a magnet for magnates, attracting industry tycoons to build sprawling estates outside of the city. Most have been sold off or transformed, but the Stoneleigh remains.

Months of renovations went into restoring the main house’s dark wood interior; the inside of the building is closed to the public apart from special tours, but it’s rentable as an event-and-meeting space. The Richmond, Va.-based Organ Historical Society—another beneficiary of the Haas family, as son Fred is a passionate player—has transported its archives to the second floor of the house.

In addition to its manageable size—it’s easy for a family to roam the entire property over just a few hours—Stoneleigh is meant to be accessible in more ways than one. Admission is free, and the property is only about a five minutes’ walk from the Villanova regional rail stop. Ramps have been built and gravel pathways paved so that those with wheelchairs or walkers can visit all parts of the garden. This, Natural Lands Trust hopes, will attract garden-goers from all over the region, not just the Main Line.

“Stoneleigh is a public garden, and public gardens are for everybody,” said Kauffman. “Everyone should have access to this beauty, to learning about plants.”

While natural beauty takes center stage, Stoneleigh isn’t just about aesthetics. A big part of the garden’s mission is to promote reverence for, not just access to, the natural world.

With workshops, tours and the property itself, part of Stoneleigh’s programs will teach visitors about sustainable landscape practices such as stormwater mitigation, soil erosion, planting for biodiversity and using native plants, as well as raising awareness about the work of Natural Lands Trust.

“We’re incorporating best practices using native plants into a Main Line country estate,” said Kauffman. “It shows people that if we can do it in a place like this, they can do it at their homes and businesses.”

For example, there are 14 acres of turf on the property, but Kauffman has plans to reduce that number. A portion is designated to become a meadow, designed to increase habitat for insects, migrating birds and small mammals. The garden is already a vibrant habitat for wildlife: Kauffman has spotted five different species of snake in addition to red foxes, coyotes, raccoons, chipmunks, squirrels, groundhogs, salamanders, toads, rare species of birds, even a bald eagle—and deer, of course.

But they’ll also, er, cut down on how often they mow portions of the lawn.

“We’ll stylize it, but we want to let it grow long—you don’t have to use machines to cut your grass so often,” Kauffman explained. And when workers do tighten up the grass, they’ll use greener, battery-powered mowers and shears rather than heavy, gas-powered machinery.

Stoneleigh uses other sustainable landscaping practices, too. Leaving plants standing in the winter rather than cutting them down, for example, provides places for

bees and nesting ground birds to overwinter. The staff plants native species in the landscape, sourced from local and regional nurseries when possible, instead of commonly used non-natives—American euonymus instead of a privet, for example, or pinkberry instead of boxwood. They’ll source leaf mulch from local contractors and manage compost on site, with a goal of never having to take waste off of the property.

The Stoneleigh staff will keep programming light for their first season, but there are already ways to get involved; monthly volunteer days will give folks the chance to help out in Stoneleigh’s gardens. They’ll hold classes for adults around sustainability in the garden, bird walks and big tree walks, and collaborations with the Organ Historical Society, which is installing an instrument in the house’s basement. For garden members, they’ll offer evening events for picnicking in the summer and a special silent film screening featuring the organ’s music in the fall.

When Stoneleigh opens its doors to the public for the first time on May 12, this space, once beloved by a single family, will enter a new chapter as a place where thousands can benefit from its vibrant life and natural beauty. Natural Lands Trust will enter a new phase of essential conservation work along with it.

The organization has had experience managing garden spaces on preserved lands, Axelrod notes, but Stoneleigh is its first public garden.

“We’ll be able to see what happens when people who are deeply committed to sustainability, saving land and preserving wildlife nature take over a garden,” Axelrod said. “Those values drive everything behind Stoneleigh.”