photos by Kriston Bethel

Building Bridges, Planting Seeds

by Nancy Chen

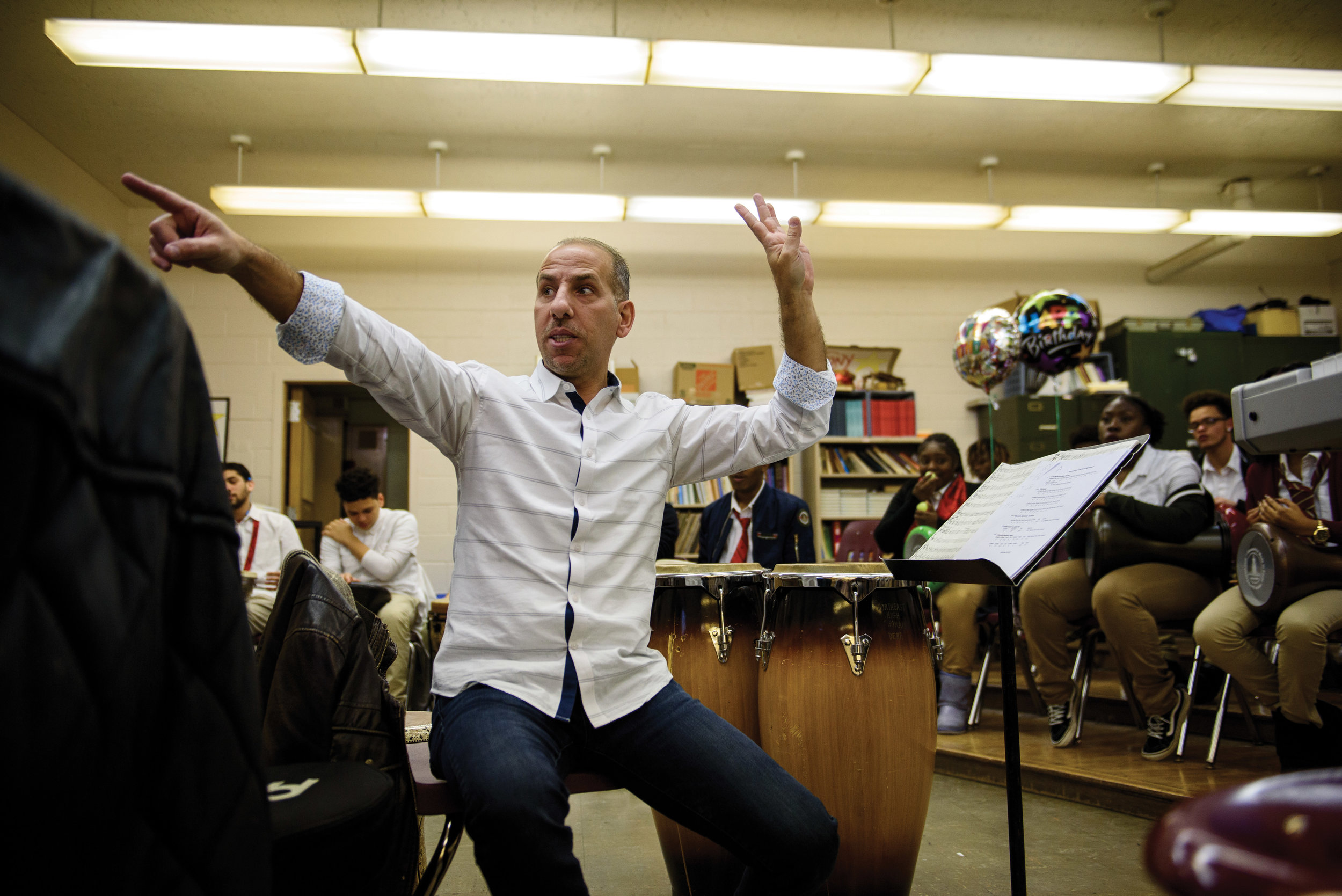

Once a week, master percussionist Hafez Kotain holds court in Jay Fluellen’s music class at Northeast High School in Philadelphia. During the 50-minute percussion lesson, an infectious energy and rowdy enthusiasm fills the room as every single student picks up an instrument and contributes to the rhythm. The group of 30 students are mostly boys, between 15 to 17 years old. Beyond that, it’s extremely diverse in terms of ethnicity—a mix of black, African-American, Hispanic, and a few Asian, Arab and white—as well as individual personality.

Some of the students are loud and disruptive, easily heard from the other side of the room. Others barely utter a word the entire time. What’s interesting to observe is that the most introverted students hit their drums just as loudly as the most vocal and clearly extroverted students. Outside the classroom, in the crowded and more anonymous hallways, many of these students probably never interact with each other. When they play rhythms together in music class, they are each finding a voice through their drums, and also learning to speak together.

Working with Fluellen, himself a professional musician and composer, Kotain teaches the students an assortment of both Middle Eastern and Latin rhythms, explaining along the way that each rhythm is associated with specific countries: “The laf and baladi rhythms are found in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Egypt, but not Morocco or Algeria. You also find them in Latin America, too, under a different name. You find the same rhythms in Latin America and the Middle East, because these rhythms all come from the same root in Andalusia.” Playing samples of each beat as he discusses them, Kotain creates a musical social studies lesson.

Smiles and laughter break out in the middle of boisterous drumming—one percussion pattern after another. Playing certain instruments seems as strenuous as some gym classes. Students are encouraged to try a new instrument every time, so it may be doumbek (a goblet-shaped drum that is common in the Middle East and North Africa) this week, then claves or maracas the next.

When he’s not teaching percussion to everyone from kindergarteners through college and beyond, Kotain plays as a core member of the Al-Bustan takht (traditional Arabic music platform) ensemble. Now in his early 40s, he speaks of carrying three cultures within him from three countries: the United States, from being in Philadelphia for more than 12 years; Venezuela, where he was born and first thought of as home; and Syria, where he lived during his formative teenage years, and where he won the top spot in Syria’s national percussion contest five years in a row.

When asked about his work with Al-Bustan, Kotain spoke passionately about the impact of teaching. He believes music is a form of therapy that brings people of all ages and backgrounds out of their shells—no matter how shy they may be and no matter what emotional baggage they may have brought to the lesson. Reflecting on the social and political climate at home and abroad, he said, “When some people think of the Middle East, all they think of is war, and—I don’t even want to say it—terrorism… What I do, with percussion and music, is to show the opposite—to show that there is a rich culture behind it. When I teach, I see over and over that people who don’t understand each other’s language can come together through the music. We don’t know what’s outside the door, with all this mess going on worldwide, but in the classroom we keep things positive. When we are together in music class, I see everyone come together in a kind of union. We call this sagrado [teamwork] in Venezuela.”

The percussion class led by Kotain is part of a multilayered, yearlong project called Tabadul led by Al-Bustan Seeds of Culture, a Philadelphia-based arts organization that is a national leader in presenting and teaching Arab culture. Tabadul, meaning “exchange” in Arabic, exemplifies Al-Bustan’s mission to promote cross-cultural exchange across ethnic, socioeconomic and religious boundaries.

The radical diversity of Northeast High School and the Northeast Philly community makes it fertile ground for Al-Bustan (Arabic for “the garden”) to sow the seeds of cross-cultural understanding and exchange. The Northeast is a popular area to resettle immigrants and refugees since it has access to public transportation, health services and affordable homes.

Serving Rhawnhurst, Oxford Circle and Fox Chase (among the Northeast Philly neighborhoods that have grown increasingly diverse through successive waves of immigration), NEHS is a microcosm of the wider diversity of the entire city, and perhaps the entire world. NEHS is the largest school in Philadelphia, with 3,400 students enrolled this school year, around 700 of whom are enrolled in the English as a second language (ESL) or English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) programs. About 60 languages are spoken in its hallways. And as an amusing bit of trivia, it is where Tony Danza tried his hand at being an English teacher, as documented in the 2010 A&E reality series “Teach: Tony Danza,” and his bestselling memoir “I’d Like to Apologize to Every Teacher I Ever Had: My Year as a Rookie Teacher at Northeast High.”

“While there’s a lot of diversity in the school, we hear of experiences of isolation and lack of communication. Parents feel like they don’t come into the school except to deal with disciplinary infractions,” said Nora Elmarzouky, Al-Bustan’s director of education. Al-Bustan has been collaborating with NEHS on and off for 10 years, offering programs that create opportunities for students, the school community and the broader city to come together and share the best of what different heritages and cultural traditions have to offer.

In the wake of 9/11

Al-Bustan was founded within a year after the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. Its first program was an Arab language and culture summer camp in July 2002. Founder and Executive Director Hazami Sayed wanted to create a supportive environment where Philadelphia youth (including her two young sons) could be immersed in the richness of Arab arts and culture.

Since its founding, Al-Bustan has been a secular and nonpolitical organization that focuses on presenting and teaching Arab arts and languages. The staff often encounters the terms “Arab” and “Muslim” being used interchangeably or mistakenly conflated. “Arab” refers to ethnic identity. “Muslim” is a religious affiliation.

“There’s an assumption that because we’re an Arab cultural organization we must be a Muslim organization. We certainly address Muslim religious culture as there’s a lot of overlap, but they’re not synonymous. Not all Arabs are Muslim and not all Muslims are Arab,” explained Elmarzouky.

Additionally, there is a tendency to view “Arab” as a monolithic identity, when contemporary Arab heritage is extremely heterogeneous. Today, Arabs reside in the 22 countries that are part of the Arab League, with a combined population of 423 million people. Someone who is Arab may be from Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates or Yemen.

Hannah Erdogan is a high school senior who has been involved with Al-Bustan for the past 10 years, since she first participated in Al-Bustan camp at 6. Erdogan grew up in suburban Yardley, about 40 minutes away from Philadelphia. Born in the U.S. to Egyptian and Turkish parents, Erdogan went to Al-Bustan camp because her parents wanted her to stay connected to her Arab heritage.

“I really looked forw

ard to camp because it was the first time I was with people like me, in a community of our own. It was very different than my experience in school,” recalled Erdogan. “There were both Arab and non-Arab children—everybody was interested and open-minded about Arab culture. Participating in the camp and other Al-Bustan programs has assured me that I’m not alone. There are people like me who live in America, and I don’t need to hide the fact that I’m different. The camp really encouraged us to celebrate and learn from each other’s differences.”

Concurrent to the launch of the camp, Al-Bustan’s presence in Philly schools started as a mentorship initiative with an all-volunteer network of Arab-American professionals looking for ways to support Arab-American youth who were experiencing social tensions after 9/11—being targeted or attacked by their peers. Sayed recalled, “A group of us who were working in fields like law, education or pursuing graduate studies came in and tried to help them navigate a tough environment. Arab kids were getting into trouble and receiving disciplinary infractions. We encouraged the youth to stay in good academic standing so that things didn’t get worse. We met with students weekly after school and helped create a student club called Arab Future Leaders.”

Over the years, Al-Bustan has expanded and implemented different iterations of programs in response to the evolving needs in its partner schools. With increased financial investment, the organization now supports teaching artists during school and in after-school programs at NEHS, the Moffet Elementary School in Kensington, and the Albert M. Greenfield School in Center City.

Sharing the same ‘fears and hopes’

In November and December 2015, terrorist attacks in Paris (by an ISIL terrorist cell) and in San Bernardino, California (by a Muslim Pakistani-American couple), brought on a new wave of anti-Muslim rhetoric and instances of vandalism, death threats and hate crimes across the country, according to USA Today and advocacy groups. In Philadelphia, a severed pig’s head was left on the sidewalk in front of the Al Aqsa Islamic Society in Kensington. At NEHS, school administrators perceived the need for increased support for Arab and Muslim students, many of whom were new to the U.S. and were feeling isolated and ostracized. Some students even stopped coming to school because they didn’t feel safe, according to ESOL staff, who added that the students didn’t feel physically threatened so much as marginalized by society. At the administration’s invitation, Al-Bustan staff started convening female Muslim students through a group called the Muslim Girls Culture Club.

Many of the young Arab and Muslim women who have been part of the Muslim Girls Culture Club come from vastly different backgrounds and never interacted with each other before at NEHS. The club brought students struggling with isolation and transition together by highlighting what they had in common as women and immigrants. “Many of the young women in the club wore veils and traditional clothes rather than the school uniform. Language was also a challenging barrier—in some cases English was not the second but maybe the third or fourth language spoken by some of the students. We would do writing exercises, photography and other arts activities to prompt discussion and reflection, exploring their identities and how they are perceived, issues they faced. Our goal was to create a space of community and empowerment,” said Elmarzouky, who played a lead role in organizing the club.

NEHS’ former ESOL director, Patricia Ryan, recalled a turning point in the club: when the young women, with guidance from Elmarzouky and other Al-Bustan staff, made a presentation to their teachers and the administration that shared, for the first time, the personal stories of how they came to Northeast Philly.

“Many of the girls were the type who usually sat quietly in the classroom, and we never really heard them have a voice before,” Ryan said. “So when they did this presentation, it was a significant shift in how they were viewed by their teachers and how they viewed themselves—as though they gained power and gained a voice when they shared their stories. The club helped them realize, though they came from all different countries, they shared the same fears and hopes.”

A few of the girls were present at a recent Al-Bustan Tabadul community workshop that brought about 50 NEHS students and teachers together and invited them to get to know each other better as they sampled a selection of ethnic foods. There was Gulalai and Zahra, bubbly best friends who call each other sisters, both from Afghanistan, wearing hijabs (head scarves) with jewel embellishments; Salawat from Sudan, who talked about her dream of becoming a doctor and going home to Sudan to help the homeless and sick people there; Mariam from Egypt, who got slightly choked up when she confessed she was struggling to make friends in school; and Rushana from Tajikistan, who said her family fled their home after her mother, a journalist, received death threats for publicly criticizing the government. Her family fled to Russia briefly, then Turkey for three years and finally to the United States. Rushana is intent on becoming a journalist, to carry on the spirit of her mother’s work. If people ask her where she is from, she says Turkey instead of Tajikistan, because “Tajikistan is a terrible place, full of corruption,” and “Turkey is where I was reborn, where I learned that Islam was about peace, not violence and death.”

In a hallway on the school’s second floor, there is an exhibition created by the Muslim Girls Culture Club that includes a map of where the girls’ families migrated from and photo portraits of the girls overlaid with writing. Across their portraits, many girls write about wearing a hijab as part of the expression of their individual identities, while showing a clear awareness of the stereotypes that exist about Muslims in America. Another common thread across their different stories is the tension between their home life—the expectations of their family and a traditional culture—and the newfound freedom of being an American high school student.

The idea of merging photography and writing in creative expression was inspired by the work of internationally renowned photographer and Macarthur Fellow Wendy Ewald. Ewald will be doing a four-week artist residency at NEHS this spring as part of the Tabadul project, working with a cross-section of students to create photography-based public art that will be exhibited across the city. Tabadul will be Ewald’s first project in Philadelphia, in a 40-year career of collaborating with youth and community in social-justice-oriented photography projects.

Sayed has been following Ewald’s work since 2003—the beginning of the Iraq War under the Bush administration—ever since she saw a New York Times cover story with the headline “A Nation at War: Arab-Americans.” She keeps a clipping of the article, which describes how Arab-American youths who weren’t even teenagers yet were inundated with images of war-torn Iraq, showing young faces resembling their own surrounded by destruction and grief. As a counterpoint to the Arabic language primers that had proliferated in the U.S. since 9/11, most of which focused on terms like “jihad” or “Al Qaeda,” Ewald worked with Arab-American youths in Queens to create a portrait series called “The Arabic Alphabet” that showed everyday language, including the words for neighbor and peace.

Creating a home for refugees

In direct response to the global refugee crisis and the recent influx of Syrian and Iraqi refugees to Philadelphia, Al-Bustan has launched (DIS)PLACED, a proj

ect exploring the theme of “displacement” in reference to both the global refugee crisis and more local resonances, including the experience of Philadelphians who have been displaced due to gentrification. The first phase of the project is to collect and document stories of displacement. The second phase is commissioning Arab artists of various disciplines—Lebanese poet Nazem El Sayed, Tunisian muralist eL Seed, Syrian installation artist Buthayna Ali and Syrian composer Kinan Abou-afach—to create new works that explore the commonalities across these experiences.

In the project’s first phase, Al-Bustan has been meeting recent refugees and immigrants through a series of Welcome Meet & Greets that started last November. “We got the idea to do Meet & Greets for refugees after we reached out to Nationalities Services Center (NSC) and Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS). We asked those resettlement agencies how we could support the needs of Syrian refugees who have been coming to Philadelphia since 2015, and the Iraqi refugees who have been coming since 2008,” said Hazami Sayed. “Within our means as an arts organization, we realized what we could do is create a cultural space [with live music and art making] that is culturally familiar to people who have come a long way from their homes. We could create a space that’s welcoming, provides a meal, connects the refugees with other people and resources, and distributes donated goods.”

Together with NSC, HIAS and other community partners, they reached out to recent refugees who arrived in the last few months. Word spread to others who had been here longer. So far they have welcomed more than 300 refugees and recent immigrants at three events at the Friends Center (15th and Cherry streets). Speaking of a recent Meet & Greet event, longtime Al-Bustan program participant and volunteer Hannah Erdogan said, “People were meeting each other, creating a sense of community and being there for the refugees. There was an abundance of volunteers. So many people wanted to help, it was heartwarming. Everyone was smiling.”

‘I used to be just like those kids’

Donald Trump’s recent executive order to limit immigration and travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries—what many opponents are calling a Muslim ban—includes a cap on the total number of refugees to be admitted in the 2017 fiscal year to 50,000, significantly reduced from the ceiling of 110,000 put in place under Barack Obama. The order (which is still being contested and will likely move to the Supreme Court) has a very direct effect on the communities that Al-Bustan serves, including its staff members and the artists they want to bring to Philadelphia. “The current climate doesn’t change our work but emphasizes the urgency even further,” said Elmarzouky. “The silver lining is that there’s an increase of support and interest in our work. More organizations and companies want to work with Al-Bustan to counter the negative rhetoric about Muslims and Arabs.”

For better or worse, Sayed sees that the need for the organization has only grown over the past 15 years. “Sadly, due to a number of current events and today’s politics, there continues to be a great deal of misinformation and stereotyping out there [of Arab and Muslim people]. We stay focused on celebrating diversity, because it’s hard to demonize someone when you have learned something of their culture, after you’ve shared a table and talked to each other face-to-face.”

Lately, Al-Bustan has been planning to start a percussion class specifically for Iraqi and Syrian refugee and immigrant youth. When approached to teach the class, percussion director Kotain replied, “Of course I would do it! I used to be just like those kids when I went to school in Syria. Welcoming immigrants and refugees—it’s a responsibility we have. It’s a message we have to send.”