A Truly Civil War

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

In 1849, in the run up to the Civil War, Henry David Thoreau wrote in his essay “Civil Disobedience” that “All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to, and to resist, the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable.”

He references “the revolution of ’75” as such an instance, knowing that the memory of the Revolutionary War, which had ended just 66 years before, would still be deeply etched into the national consciousness. One of Thoreau’s main points of contention at the time he wrote “Civil Disobedience” was that, while America as a country was free from English rule, “a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves.” Our nation’s bloody civil war began 12 years later, and over the course of those four years, more than 600,000 Americans lost their lives.

It’s hard to ignore that our country was founded on armed conflict, starting when the boats and guns invaded from Europe and settlers wrested the land from the Native American peoples. You can still feel the results of our violent past everywhere: in the troubling statistic that there is now a gun for every man, woman and child who lives in America; in our inability to pass gun regulations in the wake of the massacre of the children of Newtown; in the militarization of our police force; and in the casual but insidious quip by a presidential candidate that “Second Amendment people” might rid him of his opponent.

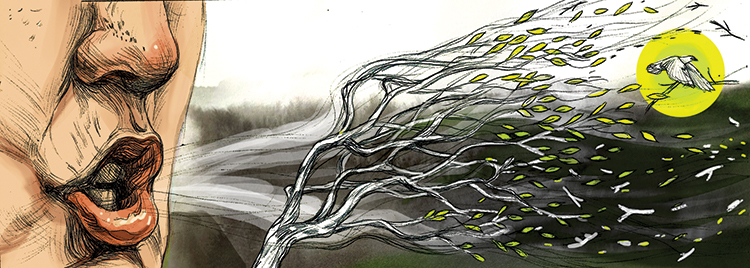

Violence is part of America’s DNA. Revolution is part of America’s DNA. But they need not forever be intertwined in a double helix.

When we examine our more recent history, we see that other revolutions have taken place by using the successful tactics of nonviolent resistance: the fight to give women the right to vote, to give black Americans their full civil rights, to give gay Americans the right to marry whomever they choose.

While these wars were not without actual casualties, the preponderance of strategies and tactics used by these movements were nonviolent. And there is now empirical evidence to show that, even in countries with dictator-led armies, nonviolent revolution is actually a more effective strategy than armed conflict.

We may all have access to guns in America, but our best bet if ever we want to overthrow the government and start anew would be to lay them down by the riverside and study how Gandhi helped to take back India, how the Serbians peacefully liberated themselves from a violent dictator, and why our own civil rights movements have been successful. An indispensable study guide will be the book “This is an Uprising: How Nonviolent Revolt is Shaping the Twenty-First Century” by brothers Mark and Paul Engler. They offer a clear picture of why these movements worked, and a blueprint for activists seeking victory whether for climate justice or Black Lives Matter.

You’ve heard the comments before, and may have even been the object of them: Protesters are wasting their time. Shouting for change won’t make a difference. What does (insert your preferred form of civil disobedience—a building occupation, blocking traffic, etc.) accomplish, anyway?

It turns out, it accomplishes a lot. It requires—of what Thoreau called a “wise minority”—the willingness not only to vote, but to undertake other collective action that will serve as a fulcrum for change. “Cast your whole vote,” he says. “Not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.”

As more and more of us push back against a government that is failing us—on climate policy, on state violence and many other issues—we need to remember that when it comes to revolution, gunpowder is no match for people power.