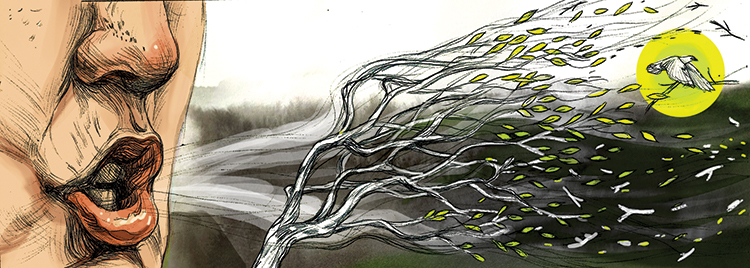

Illustration by Anne Lambelet

Sharing Our Table

by Brian Ricci

I’m fascinated by flavor.

I was raised in a small town in the New Jersey suburbs, and at a young age I could walk by myself to school or meet my friends in the town village to trade baseball cards and trap crayfish in the creeks. Many afternoons, I would come inside after running around with friends and sit at my grandmother’s kitchen table.

There, she would have some pencils, markers and paper waiting. I sat and drew while she cooked and talked. As day turned to evening, the kitchen would become a hot spot of activity. Neighbors, aunts and then my folks and brothers would arrive to socialize and eat.

Food would appear—she was the type of cook who made things appear effortless. Conversation would continue as Grandma surveyed the room: She knew what you needed before you did. After dinner, the kids would run off and play outside while the adults had a little more wine and a little more coffee.

I can still see the sky at dusk, my grandfather fast asleep, music playing throughout the house. I can smell the tomatoes plucked from my grandmother’s garden and taste the tomato ragù that she would slowly simmer all day long.

I believe the science that tells us that smells and tastes are the avenues by which we hold onto some of our strongest experiences.

Fast forward 20 years, and I cook for a living. While the fast pace and the sheer amount of time involved in preparing each dish can be overwhelming, it forces you to sharpen your focus and heighten your senses.

I once worked in an Indian fine dining restaurant in New York City that required me to toast and grind an arsenal of fresh spices daily. The act of simultaneously toasting six separate pans of spices every morning at 6 a.m.—five days a week for 10 months—leaves a lasting impression. There is a distinct moment when a spice passes from darkly toasted to slightly burnt. I can smell it before it happens.

In a San Francisco bakery co-op, I honed my skills at kneading, shaping and baking, and mastered knowing—by a simple touch or tug—if a dough was properly mixed or proofed. Smelling the crust develop during a bake was a sensory experience that bordered on addiction for me and for our customers. They knew our bake schedule as well as we did and would arrive punctually as fresh bread was decanted from our baking racks and transferred to our shelves.

Here in Philadelphia, I spend most evenings essentially doing what my grandmother did: making effort look effortless. We cooks thrive on that moment of joy when our guests eat. I tell my cooks and servers to look at a restaurant as if it were a casual dinner party we’re hosting at our house, where everyone is welcome.

And when I’m at home with my boys, with their markers or iPads spread on the table, we talk, we eat and I pour myself a little more wine.

Brian Ricci is a chef who has worked in New York, San Francisco and Philadelphia, most recently with Pub & Kitchen, Supper, Kennett Restaurant, and Brick and Mortar.