Black and White

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Forget the Lafayette vs. Lehigh football rivalry, a Pennsylvania matchup that began in 1884. The longest running rivalry in college sports is progressive students and faculty lining up against conservative university administrations—and socially conservative thought in general.

Among other causes in the ’60s, it was the Vietnam War, the fight for women’s liberation and the struggle of the civil rights movement. In the ’70s and ’80s through today, the fight continues to incorporate the history and culture of women and people of color into curricula. In the mid-’90s at my own school, Muhlenberg College, a handful of upperclassmen turned their backs to the student-selected graduation speaker because he had spewn homophobic nonsense at a fellow student. It’s good to know that—20 years later—a gay student would be the one giving the graduation speech, not watching as the schoolyard bully was given the bully pulpit.

Climate change is top of mind for today’s students, who are actively creating products, services and solutions that will help move us toward a sustainable economy. The most savvy among them are working on public policies that would put a price on carbon, the single biggest lever that would launch us into a new age. Upon graduation, they are seeking work with companies aligned with their values—or starting their own.

Students are also arguing that, in the meantime, their schools’ endowments shouldn’t profit from industries that are contributing to a climate catastrophe, and should be divested from fossil fuels. Some directors and trustees counter that they are bound to make sound financial decisions for the school rather than, as they have characterized it at Swarthmore College, “pursue other social objectives.” That a university board views climate change as any old politicized cause—and not as a threat to life as we know it—is supremely disturbing.

Boards that choose not to divest have a legally sound argument, and a practical one: The case has been made that divesting itself won’t make us less reliant on fossil fuels any time soon.

But the boards that don’t divest are, essentially, betting against the long-term success of their own students and refusing to lead a cultural shift that will get us away from fossil fuels. And, morally, we have to start somewhere: Large institutions that have cultural sway and educate young people should behave in ways that model desired behavior and create new mores.

This spring, The New York Times wrote a story about how Georgetown University may pay reparations to the families of slaves who were sold to keep the Jesuit college profitable in 1838. In 20 years, it may well be writing about whether, in 2016, the Quaker-founded Swarthmore College profited from industries that similarly exploit people and planet. This may seem an extreme comparison, but consider that in his book “Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about “the seductiveness of cheap gasoline” and how our country’s history of slavery has predisposed us to plunder at will “not just the bodies of humans, but the Earth itself,” in both cases willfully forgetting that our power and fortune is made on the back of that exploitation.

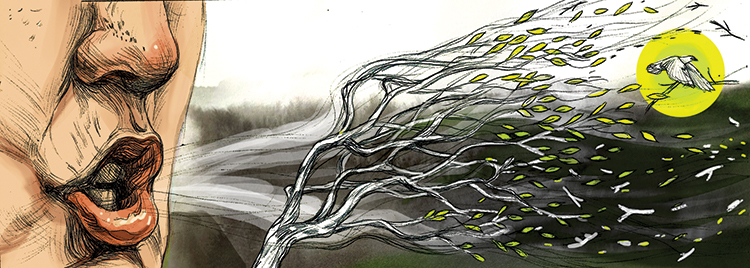

Divestment is a step toward a larger cultural shift wherein we decide to stop the plunder, both of bodies and the earth. Colleges and universities should be key places where that debate thrives and action follows, places of leadership and enlightened thought where our history informs our future. In the aspirational halls of higher education, people should be wearing the white lab coats of innovation, not hats blackened by coal dust.