Awakening

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

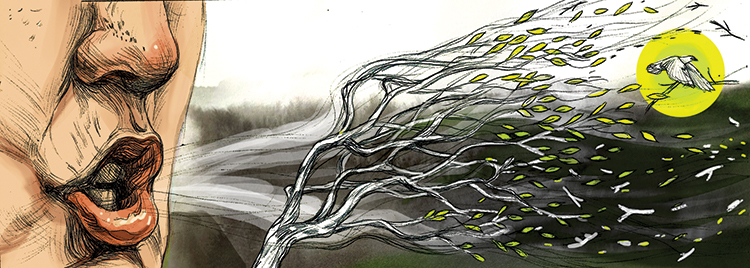

Out in the woods of Fairmount Park and across the eastern woodlands, spring ephemerals, those short-lived native flowers—twinleaf and columbine, bloodroot and trout lily—have been blooming. They come up on their own to announce the coming of spring to the few souls who might seek them out, and then go dormant when the heat of summer comes calling. They flower whether we see them or not, and disappear just as quickly.

In the Amazon rainforest of Brazil, plants native to its ecosystems are also growing. Amid the lush backdrop of protected lands that are crucial to the health of the entire globe, in sight of butterflies the size of dinner plates, a very different kind of temporary organism is popping up and then disappearing: illegal timber operations.

In Congo, and in Ghana, the unlicensed and in many cases heavily armed operators stay longer as they tear up and poison the ground, in part because the mines that give us gold and diamonds—even metals for our cellphones—take longer to root and to bear fruit. In Bangladesh, it is the wildcat shrimp farms, and in India, the granite quarries.

All of these industries are destroying the ecosystems in which they operate, but that, unfortunately, is not the most disheartening fact about their existence. In many of these places, the workers responsible—for clearcutting the forest and mining the gold and gutting the fish—are not working by choice. They are slaves.

By some estimates, 32 million people worldwide are in bondage, and many of them are children who have not known, and will never know, any other life.

In his book “Blood and Earth: Modern Slavery, Ecocide and the Secret to Saving the World” abolitionist Kevin Bales makes the argument that slave-driven industries are the third largest source of CO2 emissions on the planet. He also makes the leap that environmentalists would redouble their efforts if only they knew that by putting more pressure on illegal mining and deforestation, they may not only save the planet, but eradicate the scourge of slavery.

It’s a big leap, and it’s a heavy lift that may yet take generations. But Bales, who in his 20 years of anti-slavery work has seen the absolute worst that human beings can do to each other, remains hopeful. He believes that more and more of us are realizing that the way we treat the planet is directly related to how we treat each other, and that there is a growing movement to do better on both accounts.

His optimism is mirrored in a quote by the memoirist and poet Mary Karr, who in recounting her troubled Texas childhood comes to the conclusion that, “The world breeds monsters, but kindness grows just as wild.”

Kindness does grow wild, but we can also cultivate empathy and a willingness to act. You can make a difference by making conscientious decisions about what you buy and putting pressure on the companies you patronize. And your philanthropy, no matter your means, makes a difference.

This spring, as you lightheartedly watch the redbuds starting to wash the woods in a light pink haze, or smile at the daffodils punching through a small patch of untended dirt, enjoy the hope that you feel. Then resolve to share it with others.