Populist Mechanics

by Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Followers of advances in artificial intelligence are waiting for a tipping point they call the “Singularity.” It’s the moment in time when the computers and machines that we’ve designed are smart enough to design better versions of themselves, an event that would trigger a cascade of exponential improvement—as well as the possibility of disaster. The fear of the rise of the robots has played out in books and movies for decades, including in the long-running Terminator series.

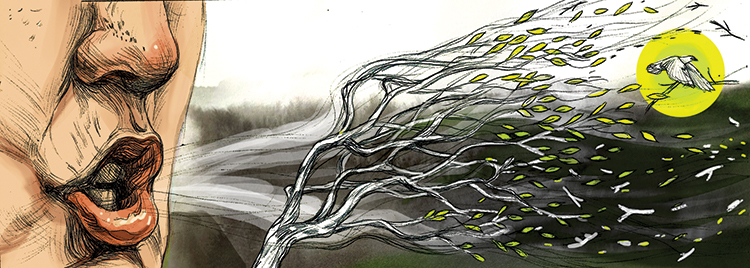

Rather than its dystopian aftermath, more recent movies such as Her and Ex Machina have also explored the softer side of the Singularity, the jaw-dropping awe and breathless excitement when “the moment” has arrived. Both films seem to capture the zeitgeist of our complicated feelings about machines: They are fascinating; they can make our lives better; they seem, even, to understand us and our desires; and they are our partners in creativity and connection. At the same time, we’re a little afraid that we’re no longer in complete control. It’s that feeling we get when we realize we’ve just reflexively checked our phone, or can’t seem to stop reading the endless scroll.

We should trust that instinct to remain the masters of our machines, especially as we move into what many in the burgeoning “maker movement” have called a second industrial revolution. Makerspaces in cities across America are offering people the chance to innovate, test out ideas and learn new skills on equipment—and in the presence of collaborators—to which they would never have otherwise had access.

An eight-year-old girl can learn how to weld and an 80-year-old engineer can finally patent that invention that his cautious company left on the milling room floor. After decades of decline in America’s manufacturing sector—and a correlated drop in the science, technology, engineering and math prowess that our country once enjoyed—our entrepreneurs stand at the ready. Inventors are on the make again: With greater access to the tools of production combined with increased access to capital in the form of crowdfunding campaigns, there seems to be a 3D printer in every garage and a prototype in every hand.

The maker movement is democratizing access to tools that were taken away during the first industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. At that time, in England and America, the knitting loom exited the living room and entered the realm of the factory, wresting tools from the hands of skilled craftsmen who were replaced by industrial machines run by unskilled workers.

The loss of those tools sparked distrust and rebellion among the craftsmen whose jobs were subsumed, including the famous “Luddite Rebellion” in England, in which workers attacked the factories and machines that had taken their jobs. It wasn’t an isolated incident, but a movement that eventually required the strength of the British army to suppress. It turns out that humans deprived of their tools can be just as angry as an army of robots insisting on autonomy.

Industrialists and capitalists continued to dominate the last century as they efficiently produced the goods that our growing population needs, and, increasingly, the things that we simply want. In the wake of all those cheap goods, we also left exploited workers, brownfields and air pollution—especially in poor neighborhoods—and created our throwaway culture.

During this next revolution, we shouldn’t let our 3D printers become pollution pushers, beckoning us with an easy good time and uncertain aftermath. This is the time, this moment of excitement and awe, to remind ourselves of our complicated relationship with making so that we don’t repeat the same mistakes all over again. We know that we can. We should also ask if we should, and how we should. We must demand more of our innovative nature, and stay smarter than our machines.

Heather Shayne Blakeslee

Managing Editor

heather@gridphilly.com