Mary Seton Corboy and Greensgrow continue to set an example

Mary Seton Corboy and Greensgrow continue to set an example

story by Lee Stabert/photos by Jessica Kourkounis

Greensgrow, an urban farm and nursery in kensington, is a superstar of Philadelphia’s sustainability community. Having earned an abundance of recent national and local press, the pioneering farm’s name is always at the ready when conversation turns to the rising tide of urban ag. But Greensgrow is important because it’s not new. It’s not trendy. The farm has been around almost 15 years, long enough for legitimacy—predating the current surge of interest in “green” projects—and it still continues to push the boundaries of what it means to grow food in a major American city, while also being a good neighbor.

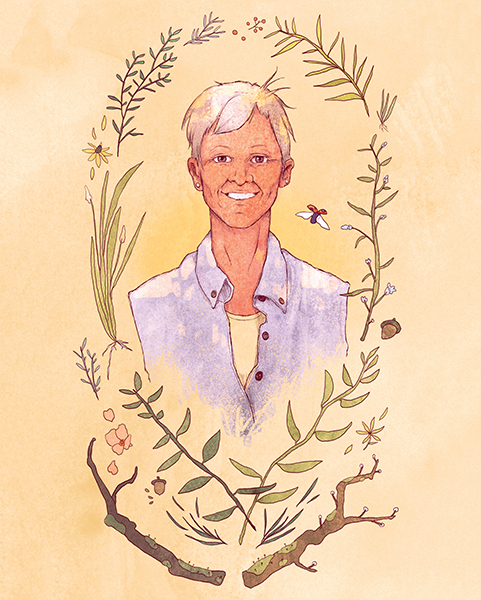

The major force behind the farm’s tremendous success is Mary Seton Corboy. A lithe woman with spiky gray hair, infectious energy and what some people might call “a smart mouth,” Corboy founded Greensgrow in the late ’90s with her partner Tom Sereduk.

Grid sat down with Corboy in the second floor office of a townhouse across the street from the farm—the abandoned building was bought eight years ago for $1,500. Over the course of an engrossing conversation, she tells the story of how a polluted, vacant piece of land became a hub for both the neighborhood and the city. It’s a narrative driven by pragmatism, innovation and a whole lot of sweat. After all, farming is hard work. Doing it in a community that views you with confusion and skepticism—while actively trying to change that image—is even harder.

A cancer survivor and practiced talker, Corboy is wily and wise. She is also funny. Very funny. It’s easy to understand why people want to work for this woman.

Mary Seton Corboy grew up in Washington, DC. Her parents were in the Peace Corps and then worked for the State Department. School was never her thing. “I was pretty uninterested in what was going on in the classroom—something that has come back to haunt me,” says Corboy. “I tell my nieces and nephews that hindsight, of course, is 20/20, or as my sister says, eighth grade is always better the second time around.”

In a pattern that would emerge over the course of our conversation, Corboy claims to be terrible at/not know much about something, and then goes on to casually recount her eventual success. “I went to grad school,” she says, “just because I couldn’t figure out what you were supposed to do after you graduate from college. I mean, they don’t give you a blueprint exactly.”

In college, she spent her summers cooking to make money. In grad school, the opportunity arose to participate in an internship at a fine dining restaurant. “I jumped at it,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘I can eat crappy food for $4 an hour or I can eat good food for $4 an hour.’ I took the good food, and became a chef.”

A few years later, Corboy was invited to help maintain the Chester County estate of painter Andrew Wyeth—another task she felt ill-prepared for. “I told them that I didn’t know how to do anything in particular,” she says. “They said all I had to do was sit on a riding lawnmower and go up and down. After about three minutes I got bored, and started doing some circles. Next thing I know, I rode the lawnmower right into the river. I don’t know how that happened. But I didn’t know the lay of the land. So, they thought that it would be kind of humorous to keep somebody like me around, [messing*] up everything that I touched. I ended up staying there for a number of years, and learned a tremendous amount about things that I had never touched on before—trees and flowers.”

Wyeth’s passion for the natural world was a good fit for Corboy: “If you know his art, he was not the kind of person who wanted fancy gardens,” she says. “There’s no way you’re going to confuse Andy Wyeth and [renowned Philadelphia socialite] Dodo Hamilton. He could look at a tree growing out of a stump of mud and think it was the most beautiful thing in the world, and he would look at a flower in a vase and go, ‘God, whose idea was that?’ So, I didn’t exactly develop my sense of aesthetics of flowers while I was there, but I did learn a little about planting tomatoes, peppers and onions and the seasons of things.”

It was around this time that Corboy met Tom Sereduk. While she had little experience in farming or horticulture, Sereduk had a science background. He had always been interested in plants and flowers, and was experimenting with hydroponics.

“It took me years to figure out what he was talking about,” says Corboy with a laugh. “So, I just kind of landed here by chance. I think I fell out of a lot of the other revolutions—but I can’t fall out of this one now, because I’m in charge.”

Greensgrow itself began with a simple question: How do you grow produce and get it to restaurants as quickly as possible, so it’s as fresh as possible? In 1998, the pair started growing on a traditional farm in New Jersey, but they were both living in the city. “I had been reading a lot of articles in the Inquirer about vacant land,” explains Corboy, “So, we reached an agreement: If I could find land in the city—and it made sense—then we could do it in the city.”

Corboy wasn’t familiar with Kensington when she began her search. “I was driving around looking at the different neighborhoods,” she recalls. “I called my housemate, Al, and he said, ‘Where are you?’ I looked around the skyline—there were more factories then—and I said, ‘I’m not sure, but I think I’m in Pittsburgh.’”

“It’s ironic, because now I’m a huge seller of this neighborhood,” she continues. “When I lived downtown [Corboy now lives in Fishtown], people would say, ‘You come down here every day?’ I was like, I didn’t cross the river in a boat. I could spit and hit my house. You can see it. I live downtown. But that was part of learning the culture here. They considered going downtown to be—like everybody had to get together and discuss it first. So, I kind of hid where I lived, because people were already judgmental about what we were doing—there were all kinds of crazy stories going around about who we were.”

Eventually they found the small plot of land at the corner of Gaul and East Cumberland that would become Greensgrow—it was a brownfield site that had been cleaned up by the EPA. “It had a fence around it and it had sunshine, but it had nothing else,” says Corboy. “No gas, no water, no electric. No nothing. Just a fence. And we were coming in very close on our time limit. We had to get growing by a certain date in order to harvest by a certain date, otherwise the year was going to be a total wash.”

In its infancy, Greensgrow focused on hydroponic lettuce, sold wholesale to local restaurants. It was not smooth sailing. “It was a comedy of errors,” explains Corboy. “The first year was such an unbelievable struggle. It was all the things that we never thought about—that people were going to steal from us, that we had no bathroom, we had no cover, we had no facility, no place to get a glass of water. We had nothing. And at the end of the year, we really walked away thinking we’re just not going to deal with this. It’s crazy.”

But they regrouped, rented a Port-A-John and forged ahead. Year two they just barely broke even.

Corboy and Sereduk went to Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania for help. “They said to us, ‘There is absolutely no way you guys can survive,’” recalls Corboy. “I mean, no way. There’s nothing to get my ire up like somebody telling me I can’t do something. So, we went right back to the drawing board, and came back for round three.”

Over the next few years, things began to change—the original business model was untenable, so Greensgrow needed a new plan. “We built a greenhouse,” says Corboy. “We diversified the operation so that we grow very little hydroponic lettuce anymore. 95 percent of our business is retail and only five percent is to restaurants. I got so tired of paying parking tickets when we were delivering. You go out delivering, you get caught in traffic, and you’d be out with lettuce wilting in the back of the truck for seven hours. It was always going to be an uphill battle. So we got into the nursery business. I knew nothing about flowers.”

But flowers were something people in Kensington did know something about. “That changed our whole relationship with the neighborhood,” explains Corboy. “People thought we were about as strange as we could possibly be. And they knew it was a brownfield site. They knew that the last people they had seen on the site had been dressed in full clean-up gear. And here Tom and I were out there in our shorts and flip-flops—two white kids burning up in the sun, picking little heads of itty bitty lettuce. They just thought we had it all wrong. But when we opened up selling flowers, that was something they understood.”

It was around this time that the idea for a CSA developed. “I didn’t quite understand it, but more people were joining them,” says Corboy, adding to the list of things she was ignorant of before conquering. “A lot of people I knew were dissatisfied with them. You know, the whole joke about, ‘Oh no! It’s August; we’re going to get 35 heads of cabbage and 42 pieces of zucchini.’”

“I was talking to a friend and he was saying, ‘I want to support the idea of a CSA—I love fresh food—but the kind of food I eat is the kind of food you deliver.’ So, I thought, that’s what this city needs: It needs like a ‘gay’ CSA. [Laughs] I mean, something geared towards the small urban couple. Let the people who have the eight kids get the big CSA with all of the cabbage in it. Let the vegetarians have those. I’ll make a CSA that’s got bread and cheese and good chicken and stuff like that.”

The CSA has become an integral part of Greensgrow’s business and identity. What started with 25 members now has 375 (525 if you count split shares). Eric Kintzel is the current curator, building the weekly baskets with care and a bit of creativity. Because of the high demand, Greensgrow compiles their CSA using resources from various local farms (within a 75-mile radius) that utilize sustainable growing practices—organic or Integrated Pest Management (IPM). Kintzel, who has a masters in environmental science, often designs the shares around specific holidays (a barbecue theme for Fourth of July) or a particularly beautiful product. When I spoke to him, the farm was readying pesto, and he was planning a South Philly/pasta-themed week.

From the CSA came the farmers’ market. “I thought, what if someone can’t afford the CSA?” says Corboy. “If I’m already going to buy corn, I’ll just buy extra corn, and then I’ll sell it at a farmers’ market.” That was just one of a host of new ideas. “Tom left, and I just kept rolling down the road with it,” she says, “continuing to diversify the farm.”

The current challenge with the CSA is expanding its reach to low-income neighborhood residents. The resulting program is called LIFE—Local Initiative for Food Education. “It’s born out of the fact that we don’t have a lot of low-income shoppers utilizing our markets, and certainly the CSA,” explains Corboy. “I’m looking into why that is. I mean, is it perception issues? Is it education issues? Are we open at the wrong times? And it’s kind of a grab bag of everything. But just talking to my neighbors, they don’t cook fresh. How can we develop a program that can fit into their lives, get them food, and make it affordable?” To address a few of those questions, members will be able to use food stamps to purchase the CSA; the price is 21 dollars per week, or 12 percent of an average family’s food stamp budget.

One key to accessibility is stripping away some of the puritanical tendencies of the local food movement. “Just because you have access to fresh green beans doesn’t mean you can only eat fresh green beans,” she explains. “I, personally, like green bean casserole. So, I like mixing things with greens. I like mixing things with life. I like to throw all of the [stuff] in the bucket together. If I don’t have homemade chicken stock, I have no problem with using canned chicken stock.”

Recruiting participants for LIFE has pushed Greensgrow towards new—or, more acurately, old—outreach strategies. The farm again reached out to Wharton for advice and, after looking at the farm’s current plan, the experts remarked that the they were doing an excellent job with social media marketing—Twitter, Facebook, etc. “Since I just learned what Twitter was last year, I was patting myself on the head,” says Corboy. “But then they said, ‘That’s just not going to work.’ This type of marketing has to be through church bulletins, word of mouth and local newspapers.”

A cooking class is another important and innovative element of the LIFE program. Every ingredient used in every recipe must be available at a store in 19125. As Corboy puts it, “If I can’t find it at Thriftway, Food Fair or Pathmark—or some corner bodega—then we’re not going to use it as a cooking ingredient, because what’s the point?”

The classes will take place at St. Michael’s, a neighborhood church. Corboy has been using their facilities for years. Once Greensgrow launched their farmers’ market, there were leftovers—surplus strawberries became jam and tomatoes became sauce.

“I didn’t want to build a new kitchen,” recalls Corboy. “I was kind of tired of building stuff. I ran into the people from St. Michael’s and they were really open to new ideas. I rented their kitchen for a couple of days to make jam, and that went over really well. And then I started to think about using it on a regular basis, updating it, getting it certified. I thought that if I’m going to go through all of that trouble, then I should make it available to other people, too, because other people might want to have food businesses.” The kitchen will soon serve as an incubator space for local culinary entrepreneurs.

Greensgrow has grown exponentially over the years—they currently employ 17 people. “When we reviewed our original mission statement at our last board meeting, it said, ‘Create employment opportunities for the underserved,’” says Corboy. “If the underserved are college graduates with degrees in Anthropology, then we have fulfilled our mission. [Laughs] This is one of the great hurdles urban agriculture is going to have to face. The people who are interested in urban agriculture are for the most part white, college-educated. They could be doing something else.” Meanwhile, urban farms tend to pop up in struggling communities, where cheap vacant land is prevalent.

In terms of academic background, Corboy’s staff is a “mixed bag.” “But I would have to shake up the bag to find somebody who is not a college graduate,” she adds. “And that is not for lack of looking for people from this community. I could count on my fingers the number of applicants that we’ve had from the neighborhood. If you walk up and down the streets here in July or August, all you hear is the hum of the air conditioner.”

Corboy is often at her most engaging when she’s on a bit of a rant. She has strong opinions—about food, cities, work and priorities.

“We’ve noticed some hesitancy in a lot of local people, ironically, to start their own gardens,” she muses. “In an area where you think people might do more of that to save some money. But sometimes it’s very difficult to put yourself in a position to judge other people’s life choices. I will often have a conversation with someone around here about their financial woes, and they’ve got a can of beer or Diet Coke in one hand and a cigarette in the other.

“I think it’s my job to try and put something here for them to have access to—making it as easy as possible. And try to do it without hitting people over the head, teaching them about how it’s helpful to all of us in the long run. That sounds so trite, you know, like I’m heading out to the Peace Corps. But, I see it in the 13 years that I’ve been here—the obesity in the children is phenomenal. Everywhere I go, I see it. It used to be that you saw a kid out there on the street all day long. All they were doing was throwing rocks at you, but at least they were getting some exercise. Now, the streets are bare.”

Organizations like Greensgrow can only do so much—especially if they want to be sustainable. “I want to make this clear: Greensgrow is not a poverty organization, it’s not a hunger organization, it’s not even a food organization,” she explains. “That’s not why we’re here. That’s not why we started. I mean, we have been drawn in that area—and I’m glad that we are, I’m glad that we have social conscience that’s been growing and growing along with our growing and growing—but our mission, which we are getting ready to revisit now, is probably not changing a whole lot. And that is that ‘urban agriculture’—of which we have a really broad definition—has the ability to rebuild parts of the city that are underutilized and uninhabited, and by doing so, create a more livable city.”

In a recently-recorded piece for WHYY’s “This I Believe” series, Corboy begins, “I believe in the power of physical labor, and I’m not referring to the intellectual idea of force used to move a rock or the defined formula—E=mc2—that creates the energy to turn a turbine. Instead, I’m talking about plain old knee-bending, bone-grinding, blister-making labor that most of the world’s human beings engage in.”

Her three-minute talk is a beautiful ode to physicality, to marking days with visible progress, to digging ditches. “It’s something that I always knew,” Corboy says in reference to the WHYY essay. “It’s why I was happy. It’s why I became a chef. I thought that being a chef tied together the cerebral, the creative and hard physical work. By the end of the day, you were tired. And then working and taking care of the Wyeth Estate, it was the same kind of thing. And now this. To me it’s perfect.”