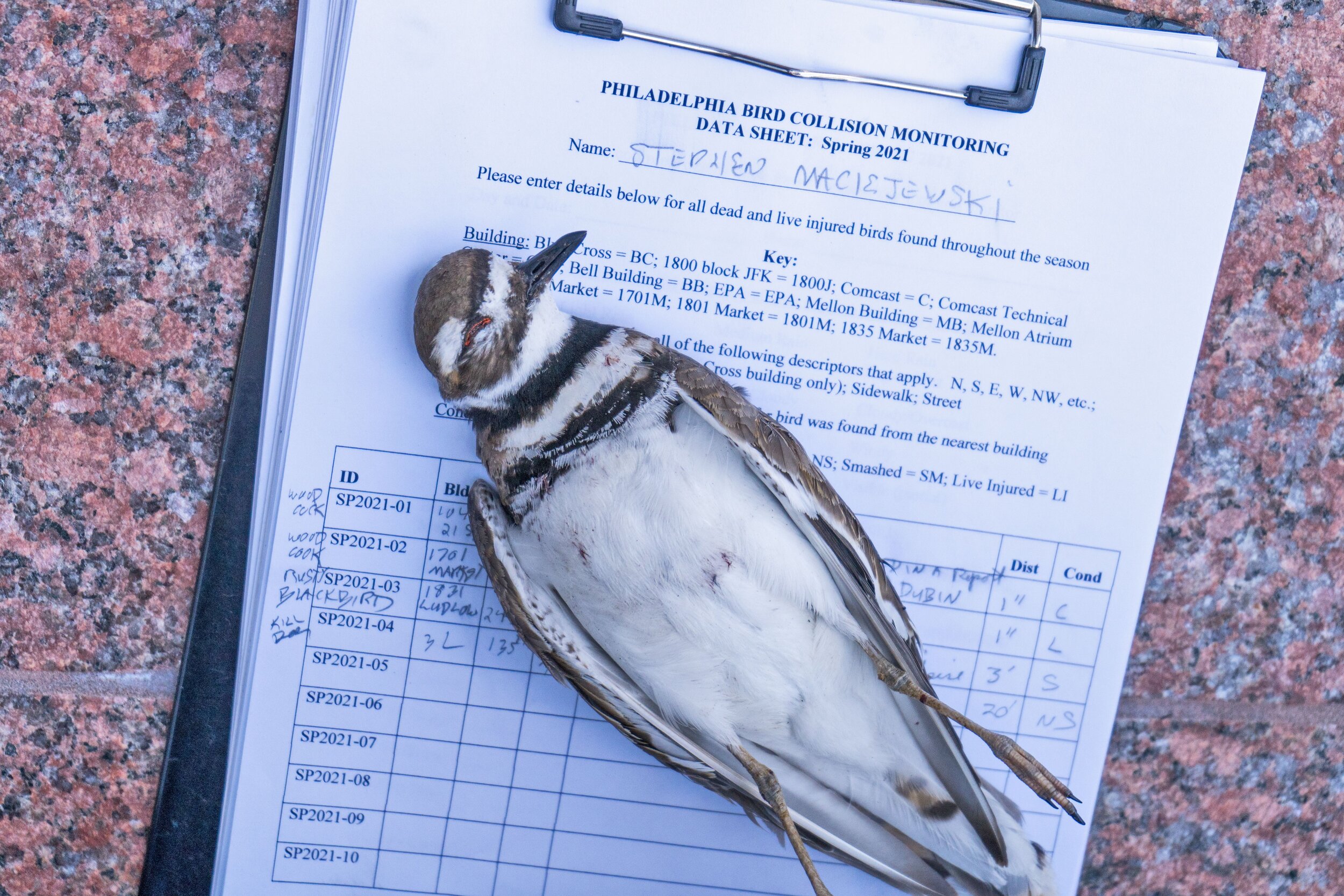

Stephen Maciejewski hit the streets of Center City before dawn one morning last October to look for dead and injured birds, just like he did every morning during fall migration.

Maciejewski, a volunteer for Audubon Pennsylvania, walked a set route around the glass-and-concrete canyons, documenting where he found birds that had collided with windows. He released the ones stunned by the impact in a sheltered courtyard where they could take some time to recover and fly off.

The dead ones went into Ziploc bags, destined for the research collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. On a normal day he would find a handful of birds. On a busy day, 20 or so. But this morning was different.

Dead birds were everywhere. Maciejewski struggled to keep up.

Near 18th and Arch streets, a custodian sweeping up in front of an office tower came over.

“His dustpan was full,” recalls Maciejewski. “He dumped 76 birds in front of me. I got the live ones out … then I had a big pile of birds. I felt the need to spread them out, and I took that photo that went around the world.”

All tallied, Maciejewski found more than 400 dead birds that day.

Every year about 600 million birds die when they collide with buildings, according to researchers. There are a lot of ways that humans kill birds, but window collisions are only exceeded by outdoor cats (which kill on the order of 2.5 billion per year). The victims range from the tiniest hummingbirds up to bald eagles with wingspans of nearly seven feet.

Birds did not evolve with glass, and often they smack into windows that reflect the sky or trees that they would like to land on. The problem is particularly severe with buildings next to green spaces, whether that’s an office building next to a pocket park, a university hall on a landscaped campus or a suburban house with a garden.

To make things worse, birds migrating at night can get confused by artificial light, and on nights with low cloud ceilings they can end up circling skyscrapers until they drop from exhaustion or land. They find themselves not in a natural stopover like a forest but in the middle of a city.

This was just such a night. Just the right, or rather wrong, weather conditions hit during the peak of fall migration, when billions of birds fly south from breeding territory in Canada and New England. Instead of making it to Cuba or Venezuela, they died in Philadelphia.

Maciejewski’s photo quickly went viral. News outlets from Philadelphia to Australia jumped on the story. On October 21, The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an op-ed by Robert M. Peck, a senior fellow at the Academy of Natural Sciences, and Keith Russell, program manager of urban conservation at Audubon Pennsylvania, arguing that we didn’t need to let this happen again.

In response, the Academy of Natural Sciences, together with Audubon organizations and the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, has launched Bird Safe Philly (full disclosure: I volunteer at this organization). The effort seeks to gather more information about bird window collisions while organizing to prevent them.

This is a problem we can solve.

Turning off lights in tall buildings is part of the solution. The organization’s Lights Out campaign, in partnership with the city’s Office of Sustainability along with the Building Owners and Managers Association of Philadelphia and the Building Industry Association of Philadelphia, will encourage building managers to turn down lights during spring and fall migrations.

“We are heartened by all the efforts in our community to join together in this critical initiative to save so many birds from unnecessary harm and even death,” stated Scott Cooper, president and CEO of the Academy of Natural Sciences, in a press release. “A simple thing like turning out lights can help thousands of birds safely navigate our challenging urban environment.”

Volunteers can also help by collecting more information about where birds collide with windows and contributing observations to the Bird Safe Philly project on iNaturalist. The information they collect can point to buildings, and even specific windows, that need to be altered to reduce collisions.

Buildings with large glass facades might come to mind as obvious bird killers, but the vast majority of window-killed birds die on houses and smaller buildings. Each window might only kill a couple birds per year, but multiplied across millions of houses, the total is much higher.

Birds might not recognize smooth glass, but we can take steps to make windows visible to birds. For example, stick-on window films that include visible patterns or strings hanging in front of a window work well, as does using tempera paint, which can be applied before migration seasons and washed off later. Organizations like the American Bird Conservancy offer online resources for anyone looking to make their windows easier on our birds.

On May 21, 1915, hundreds of migrating birds died after colliding with City Hall, newly lit up with powerful arc lamps. Artificial lights at night and windows have been killing birds for more than a century, but we can end the problem today.

Steven comes around every morning, its great seeing him but it makes me sad to see the dead birds he has collected from around my building. Keep up the hard work you do Steven.

William