Drive from New York to Washington, D.C., and it might be hard to imagine that there was once anything there other than cities and suburbs. Today a vast landscape of brick and asphalt, concrete and lawn stretches up along the I-95 corridor, broken only occasionally by marsh, farmland or forest. You might wonder what grew in the megalopolis before, well, before it was a megalopolis.

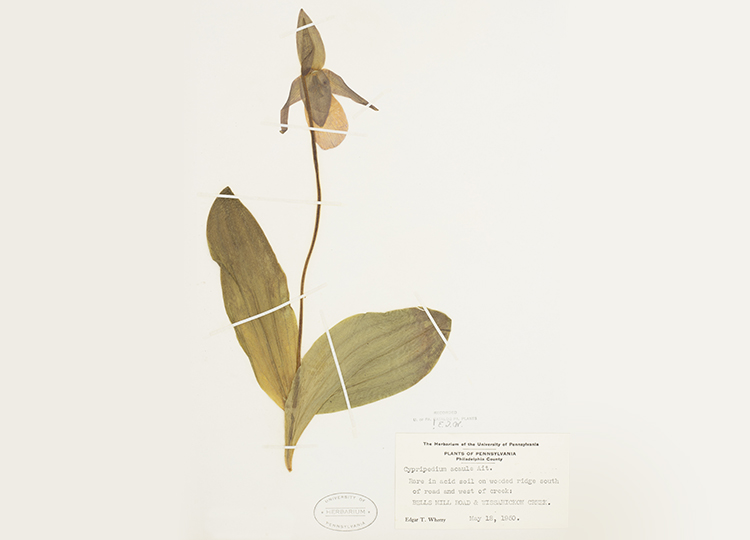

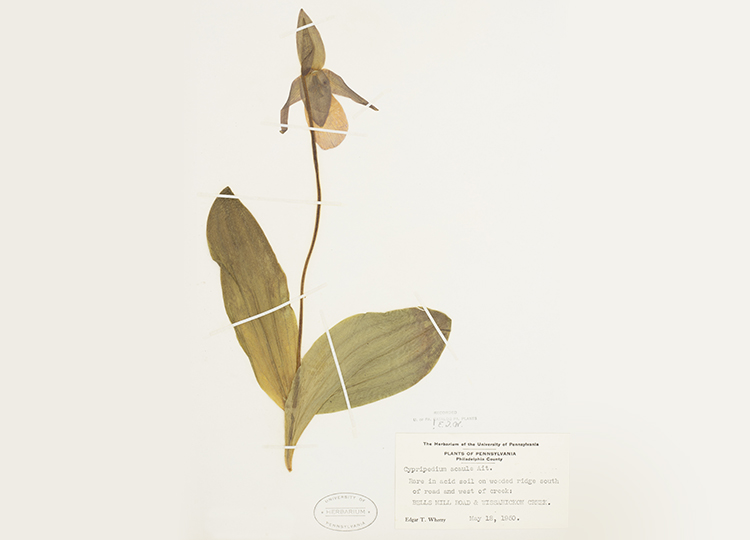

Luckily, we have a way to go back in time. For hundreds of years naturalists have collected and documented plant specimens. Many of the plants collected were preserved by being pressed, dried and arranged on sheets of paper. A collection of these plant specimens is called an herbarium. “[It] is like a library of dead plants,” explains Cynthia Skema, a botanist at the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania and lead principal investigator for the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis (MAM) Project, which is digitizing these herbaria. “Herbaria are the closest thing we can get to a time machine,” says Skema. “We know that this plant was growing in this place at this time, and this person picked it up and put it on a sheet of paper.”

The Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis is the oldest urban corridor on the continent, Skema notes. “Let’s see what we can learn from plant specimens…and get some idea of what has happened to plant diversity in urban areas.” She points to examples of certain trillium species (spring wildflowers), walking ferns and pink lady slipper orchids collected in the Wissahickon Valley Park, none of which grow there today. Skema says herbarium collections help us learn about the impact of climate change by showing, for example, how flowering dates might have shifted over time.

The challenge is sorting through all the data, says Tatyana Livshultz, curator of botany at the Academy of Natural Sciences and professor at Drexel University, which is participating in the MAM Project. “You can imagine if you wanted to know all of the species that have occurred in a particular place over a period of time, it would take you quite a long time to go through specimen by specimen and get that data.” The MAM Project, funded by the National Science Foundation, seeks to make that research a lot more efficient, says Livshultz. “So what we’re doing is getting that data for everyone who might want to ask questions about plants, plant communities [and] how species composition of the Mid-Atlantic might have changed.”

The MAM Project, now in its second year, currently includes 13 partner organizations with about 1 million plant specimens collected between Washington, D.C., and New York, says Skema. Phase one is taking high-resolution images of the specimens, phase two is transcribing the collector’s notes on each page into a database and phase three consists of assigning coordinates to the locations described in the notes.

Machines might be great at digitizing images, but they aren’t as good at reading handwriting. Skema explains that they tried optical-recognition software to read and transcribe the notes in the plant records, ranging from cursive handwriting from the late 1700s to modern computer-printed labels. “We figured out early on that it was faster for a human to sit down and type it into the database.”

About 160 volunteers, such as Susan Hepler, a master gardener and retired professor of children’s literature in northern Virginia, have assisted in preserving these vital records. “I can have my scotch and sit here at the counter and listen to NPR. Two hours later I’ve entered some records and I’m ready for dinner.”

“I love the natural history and the history of the collectors,” says Hepler, who points to the example of a prominent Philadelphia-area botanist named Bayard Long. “So this guy had a ton of records. I’m picturing him out in the woods with his loupe, his notebook and his pressing equipment.” He started in 1905, Hepler says, “and by 1920 he had 23,000 [records], in 1944 he had 62,000 and in 1956 he had 81,000.”

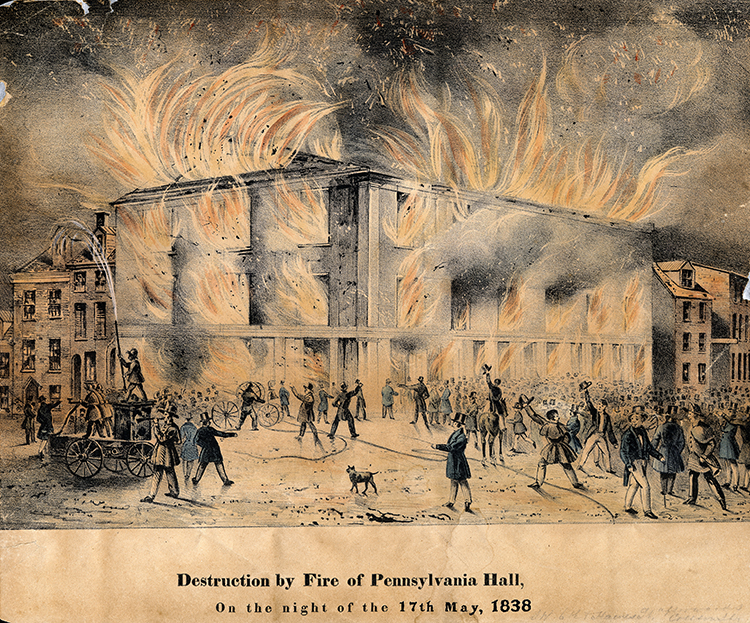

These old plant records remind us that nature lovers of today walk in the footsteps of their predecessors. Livshultz mentions the plants preserved by Benjamin Smith Barton, a prominent Philadelphia physician, naturalist and botanist active during the turn of the 19th century. One specimen, a blue vervain, catches her eye. “He indicates it was collected at Bartram’s Garden. It’s a place I love to go today to enjoy a bit of nature in the city, and I find it really fascinating to think about all these people going, 200-plus years ago, to all the same places where I go to look at plants today.”

Want to get involved? Send an email to mamdigitization@gmail.com to volunteer, and check out the digitized and transcribed records at midatlanticherbaria.org.