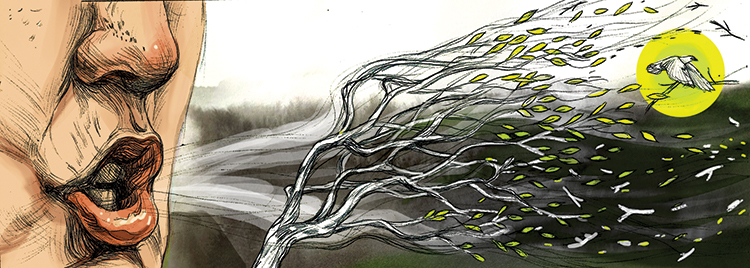

Illustration by Anne Lambelet

The Power of Not Working

by Jerry Silberman

Question: How can political power be mobilized on a local level to effect social change?

The Right Question: How does a community really have power over its future?

If you, dear reader, work for a paycheck, spend it on the things you need to live and by the end of the month are feeling a pinch for the next check, don’t feel bad; the overwhelming majority of Americans are in the same position. Apart from the obscenely wealthy, few Americans could go two months without a paycheck before hitting on seriously hard times.

It’s worth considering, then, that the more self-sufficient a community is, the more power it has. Think about the following: If you didn’t have a paycheck for six months, how much could you do for yourself that you usually pay for? Grow your food? Cook it? Replace a broken window? Repair your laptop, change the spark plugs in your car or switch out the chain on your bicycle? What skills or goods do you have that you can barter or loan in exchange for something you need? And, importantly, how many of your neighbors are willing to barter or pay in kind, with labor or goods?

Last year I traded two free-range chickens for an acupuncture appointment, and have often cleaned up a fallen tree (or dropped and removed a dead one) in a neighbor’s yard that wound up in my wood stove.

Our current society is based on unequal trade; businesses spend billions on advertising to convince us we need something, then charge us just a little more than we can afford to buy it—because we just have to have it and they know we’ll open our wallets, anyway.

The profits of Exxon, GE, Google, Home Depot, McDonald’s, Walmart, Macy’s and all the rest are based on a culture they have built that leaves us forever unsatisfied—so we get in line for a new iPhone as though our lives depended on it.

But there is a different way. Most Amish communities today interact significantly with the outside cash economy, but when push comes to shove, the skills for a comfortable life without high tech machinery are still alive and well. The community is there as a safety net for all its members, whether they need a new house to be built, or a sick child to be tended to.

As a union organizer, I realize that at least some level of financial independence is necessary for a union member to be able to go on strike. That independence, across the membership of a union, is what allows them, as a union, to exercise the power of not working, which can convince their boss to agree to make changes in wages and working conditions he may not otherwise make.

The goal of community autonomy points to a way to exercise political power, by understanding the scale at which we can be effective. Mobilizing power to pressure elected politicians to do things that they don’t want to do only works if the politician knows that we have the power to end their job. At the national level, the influence of money in politics—and the near impossibility of a viable candidate with the resources to contest the corporate consumer culture—means that we cannot put their jobs at stake. We can vote for Hillary or Donald, but either vote is basically for endless consumption, endless war and profits before people. Voting in national elections merely comforts corporate America that they are still the moral leaders of our society.

However, we can make a difference locally, which is where change must start. Just as we can choose a bike or SEPTA instead of a car, and forgo that Chilean strawberry in January, we can vote for City Council members, township supervisors or school board members (hopefully even in Philadelphia, soon). These elections are on a scale at which an organized community can make a difference.

Local politicians will do what we ask to keep their jobs, and we can therefore pursue an agenda to reduce energy consumption, hold corporations accountable for the costs they impose on all of us, and limit wasteful development or set aside green space.

We can experiment with new models of community, organization and consumption by establishing a community that can, in some small part, cut itself loose from consumer society by electing local leaders who share our agenda. These new models can, in turn, help us learn how to navigate the challenges ahead by pooling resources and skills to become more self-sufficient.

Jerry Silberman is a cranky environmentalist and union negotiator who likes to ask the right question and is no stranger to compromise.