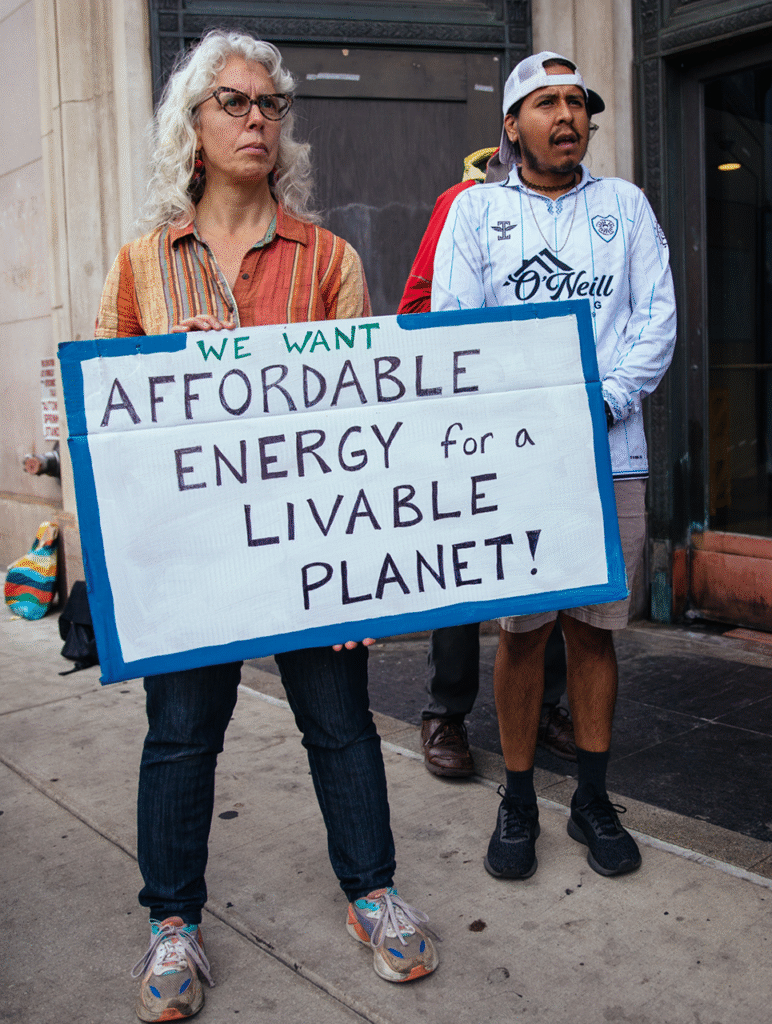

Photo by Jared Gruenwald

Making It

by Marilyn Anthony

On a textbook-perfect October afternoon, a dozen kids are busily making things in the children’s section of North Philadelphia’s Rodriguez Library. Tyliaha, age nine, is cutting pink felt into a complex shape that will become a backpack for her sister’s doll. Cianai, 11, shows off a montage of photos and hand-drawn hearts she made on a computer using Photoshop. Malaysia, nine, and Ashlee, six, are morphing cereal boxes into a castle complete with turrets and drawbridge. Scissors, fabric, paper, markers and hot glue guns are all in motion as the girls rummage through a wall of supplies to augment their endeavors. They’re participating in the Maker Jawn Intiative, an intergenerational program of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

What Marion Parkinson, North Philadelphia Neighborhood Libraries leader, most wants you to know about Maker Jawn, is that “It is not arts and crafts. Even when it looks like it’s arts and crafts, they have a purpose. The programs get boys sewing, girls doing computer coding. It crosses genders in either direction.”

The name “Maker Jawn” captures the inclusive range of program outputs. For non-natives of Philadelphia and others who’ve never heard the word, a “jawn” is a non-specific noun that can be applied to anything, so its meaning depends on the context. Their program website offers these examples: “Let me get a piece of that jawn?” and “That Frankenstein remix jawn be tight!”

The kids who attend the program are “Makers.” Maker Jawn’s goal is to provide anyone age seven and older the opportunity to follow his or her interests in a safe, free space where failure is encouraged as a necessary step of learning. The program largely serves kids, but the people behind Maker Jawn hope to eventually draw in adults as well. The program offers access to materials, technology and guided support that would otherwise not be available to most participants. Project Coordinator Sarah Winchowky estimates attendance is between 700 to 1,000 makers monthly, with the majority falling between the ages of eight and 12. A Maker-made, hand-lettered sign—embellished with many hearts—hangs on the Maker Jawn door at Widener Library, and, with Dante-like simplicity, captures Maker Jawn’s appeal: “Hi People. You will have fun in this room.”

Maker Jawn launched in 2013. That same year, its “Connected Messages” project—which produced five electronic, interactive murals of multi-colored LED lights—won a Red Ribbon Editor’s Award and a Blue Ribbon Educator’s Award at the World Maker Faire in New York City. Funded in large part by a three-year, $1 million grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Maker Jawn offers programs in five North Philadelphia branch libraries: Kensington, Cecil B. Moore, Ramonita de Rodriguez, Lillian Marrero and Widener. The McPherson branch will begin offering programs this month.

The maker mindset

At Cecil B. Moore, kids are using GarageBand software, MIDI keyboards hand-built from scraps, and a MIDI sampler to generate mash-ups, club mixes and sci-fi sound effects. They share their creations with friends by uploading files tothe Internet-based audio platform SoundCloud.

At Widener, participants built a six-by-six-foot raised garden bed from hay bales and grew giant pumpkins, glass gem corn, red amaranth and rainbow chard. At harvest time they made masks and posed with their pumpkins for a photo shoot, popped the corn in the library kitchen, and composted whatever pumpkins were too big to be carried or rolled home.

Maker Jawn participants have built motorized toothbrush robots, and made stop-motion animations and short movies complete with sets and costumes such as the Kensington branch film Where the Spooky Things Are.

While some cool, funny and imaginative things result from Maker Jawn activities, the final product is less important than the process of learning. Elliot Washor, co-founder of the nonprofit Big Picture Learning, calls it “thinkering—engaging the hands and the mind.” His organization is“dedicated to a fundamental redesign of education in the United States,” he says. Observers of a Maker Jawn session may be impressed by what the children are making, but will be even moreimpressed by how they are behaving: relaxed and immersed in their work, not bored, not nervous about interacting with a grown-up. They exude a sense of belonging in the library, happy and content.

Yasmin B. Kafai, University of Pennsylvania professor and chair of the Graduate School of Education’s “Teaching, Learning and Leadership” divisions, is an acknowledged leader in learning theory whose pioneering work has received funding from the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation. Kafai was an early partner with Maker Jawn, collaborating on the award-winning“Connected Messages” project.

Kafai is a strong advocate of the “maker mindset.” She says Maker communities are interest-driven, are not restricted by age or ability and contain a powerful social component. Makers can be part of an intergenerational learning environment where experience counts more than age. “That’s something we rarely have in school classes,” Kafai says. “In the Maker community, kids can be in the position of mentoring. We have forgotten that this is an important and successful learning model which doesn’t segregate by age.”

Kafai applauds the maker movement’s high tolerance for failure, acknowledging that failure is always part of the creation process. “It would be very rare to get a program or a design working the first time around… Productive failure is built in the process. You have to go back and examine what isn’t right, maybe go find someone to ask the right questions so they can help you fix it, then try again.” Permitting this style of learning through productive failure, she feels, is often dismissed as“too messy for our traditional educational process.”

The mentor effect

Each year, Kafai sends Penn students from the Graduate School of Education into city neighborhoods to spend an academic year observing how learning happens outside of school. Kai Evenson, M.S Ed., a curricular technology consultant for Bates College, observed the Maker Jawn sessions in 2014–15 when he hoped to identify a method for measuring impact.

Evenson describes the learning paradigm of Maker Jawn as encouraging movement from “hanging around, to messing around, to geeking out. You can’t assign a number to its impact. It’s much more qualitative.” He feels the relationship Makers develop with Maker Mentors may be more valuable for long-term impact than any other program element. As the library’s Parkinson observes, “Makers seem to latch onto the mentors. Each one of our Maker Mentors has their own little cult following. [The youths] are seeing people who have college degrees in art, engineering, science—and they are interacting with mentors who are not buttoned down and are doing really cool things.”

Ten adults, ranging in age from their 20s to 40s, comprise the Maker Mentor team. These part-time staffers bring a range of skills as varied as the number of roles they fill. Makers are encouraged to go anywhere their interests lead them—engineering, digital media, electronics, programming, cooking, sewing, illustration, gardening and construction are all fair game. One of the greatest challenges for these multi-talented mentors is resisting the urge to take over a project and

“fix” it. Mentors work at asking the right questions, being excited about a child’s task, and—especially for the older kids—knowing when specific technical instruction will help advance their project.

Maker Mentor Goda Trakumaite, 27 and equipped with a philosophy degree, is “Miss Goda” to her Makers. Moving around the room, she checks in with her young creators, watching for points of frustration that may lead to giving up on a project. She looks for times when encouragement is the answer, or moments when instruction will urge a child on. Fear of failure, or of breaking something, often inhibits young Maker Jawn participants, but encouraging them to tinker helps them move past their reluctance. Swarming like bees around a hive, the young particpants constantly come to Miss Goda to show or ask. The castle builder holds up a tiny door she has cut out of a cereal box. Miss Goda says, “You could attach that with a hinge. Do you know what a hinge is?” She didn’t, but she does now, and her castle has the drawbridge to prove it.

Mentors encourage self-expression by being non-judgmental and expecting that same attitude from all participants. “It’s great when people bring their friends or teach other people skills they’ve already learned,” Trakumaite says. “I love when a kid comes in and says ‘Today I want to make a kite,’ or ‘I’m going to make a book for my dad’s birthday,’ or ‘Can I sew up a hole in my backpack?’ It’s cool that they think of the program as a place where they can come to try out something new or to make or fix something they will actually use in their life.”

Hannah Holby, a 30-year-old artist Maker Mentor at the Kensington branch, celebrates Maker Jawn for allowing participants to develop new skills, along with the confidence to apply those skills to projects that are meaningful to them. “I like that this program doesn’t focus on the end result,” says Holby. Film projects are especially gratifying to her, since they involve diverse groups working together. Kids take over the storyline, add scenery and costumes, and then ad-lib the dialogue. Kensington branch Makers proudly rattled off names of the films they’ve made, including a cooking show on roasting cauliflower. They accidentally set off the library smoke alarm, but nonetheless it was so popular that beginning this month, the Kensington Maker Jawn crew will be producing a monthly series of cooking shows on YouTube, followed by a cookbook.

Not about the jawn, all about the science

The Makers’ excitement at the Kensington library contrasts with an appraisal of school that nine-year-old Tyliaha offers, along with a project she worked on there. “School is just work, work, work. We have a list of what we’re supposed to do and we’re supposed to have a break, but we don’t ever have any. We never get a break. The only thing we do that’s fun is science. It’s fun because it’s a lot of projects and I like to do projects.” Tyliaha’s science project was to mix flour, salt and water in a plastic bowl, then let it dry into a beige disk, about five inches in diameter. “What are you going to do with it?” she is asked. “I don’t know yet,” she shrugs; a gray disk can’t compare to that pink backpack she’s making for her sister’s doll at Maker Jawn. Studies show that outcomes-based learning is one of the approaches that helps keep girls interested in science, and innovative educators are taking note.

Much of the interest in maker activity can be attributed to the dismal scientific literacy rating U.S. students scored (21st out of 30 countries) in the Program for International Student Assessment in 2009. A 2010 report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology stated that “the problem is not just a lack of proficiency among American students: there is also a lack of interest in STEM fields.” President Barack Obama, in a 2009 address to the National Academy of Science, voiced a growing concern. “I want us all to think about ways to engage young people…to be makers of things, not just consumers of things.”

“Doing science” is the lure of MakerFaires. First held in the San Francisco Bay area in 2006, MakerFaires now occur around the world. The White House held a MakerFaire in June 2014, and that same year Google and Make: Magazine held their third online maker camp, attracting more than two million global participants. Intel, the chip maker, in a report called MakeHers, compared the maker movement to 1970s computer clubs, a phenomenon they claim gave rise to “a new wave in software programming, semiconductor design, and technology products, and ultimately to the world of technology as we know it today.”

Such aspirations are tempered by comments in a Maker Movement report by Dale Dougherty, president and CEO of Maker Media and publisher of Make: Magazine. “I have observed,” Dougherty says, “that parents have forgotten what tinkering is. Playing and entertainment—even with cardboard boxes and scissors—have been forgotten. Making is reintroducing this … and gameplay to people’s lives.”

It’s not easy to design a lesson plan for people of varying ages and skills. Sarah Winchowky and her team, the architects of the Maker Jawn program, are experimenting to hit the right balance of structure and openness. This year, Maker Jawn will introduce monthly themes, such as “Elemental,” where Makers will explore component parts of products as diverse as movies, circuits or cakes. Maker Jawn avoids top-down programming. “What we do is facilitate. We do not dictate,” says Winchowky.

Miss Goda notes, “There’s a lot of value in being less directed, but it’s more chaotic, and it isn’t for everyone.” Her colleague Holby adds, “I love it when a Maker takes something they’ve learned and comes up with a new project of their own. We all love being inventors, designers and creators, not just participants.”