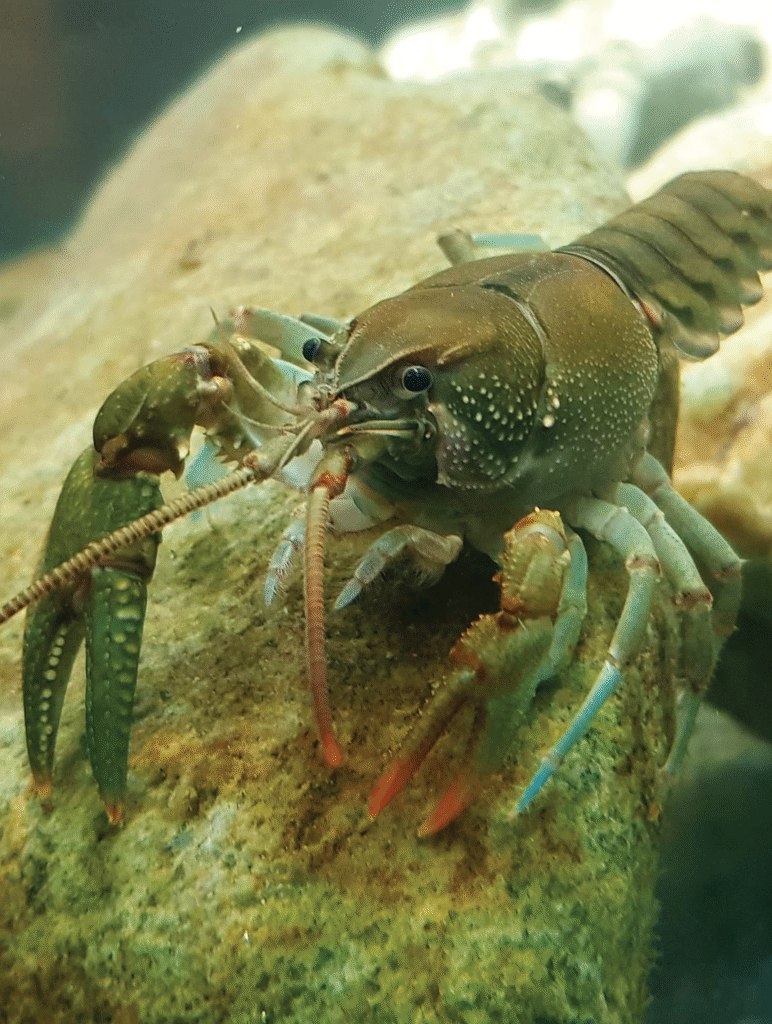

Red-eared sliders are turtles that make bad pets, but that doesn’t stop them from being sold to people who don’t know better. They start off as cute hatchlings, but they can live 40 years and grow as large as dinner plates, at that point needing way more space than the usual aquarium.

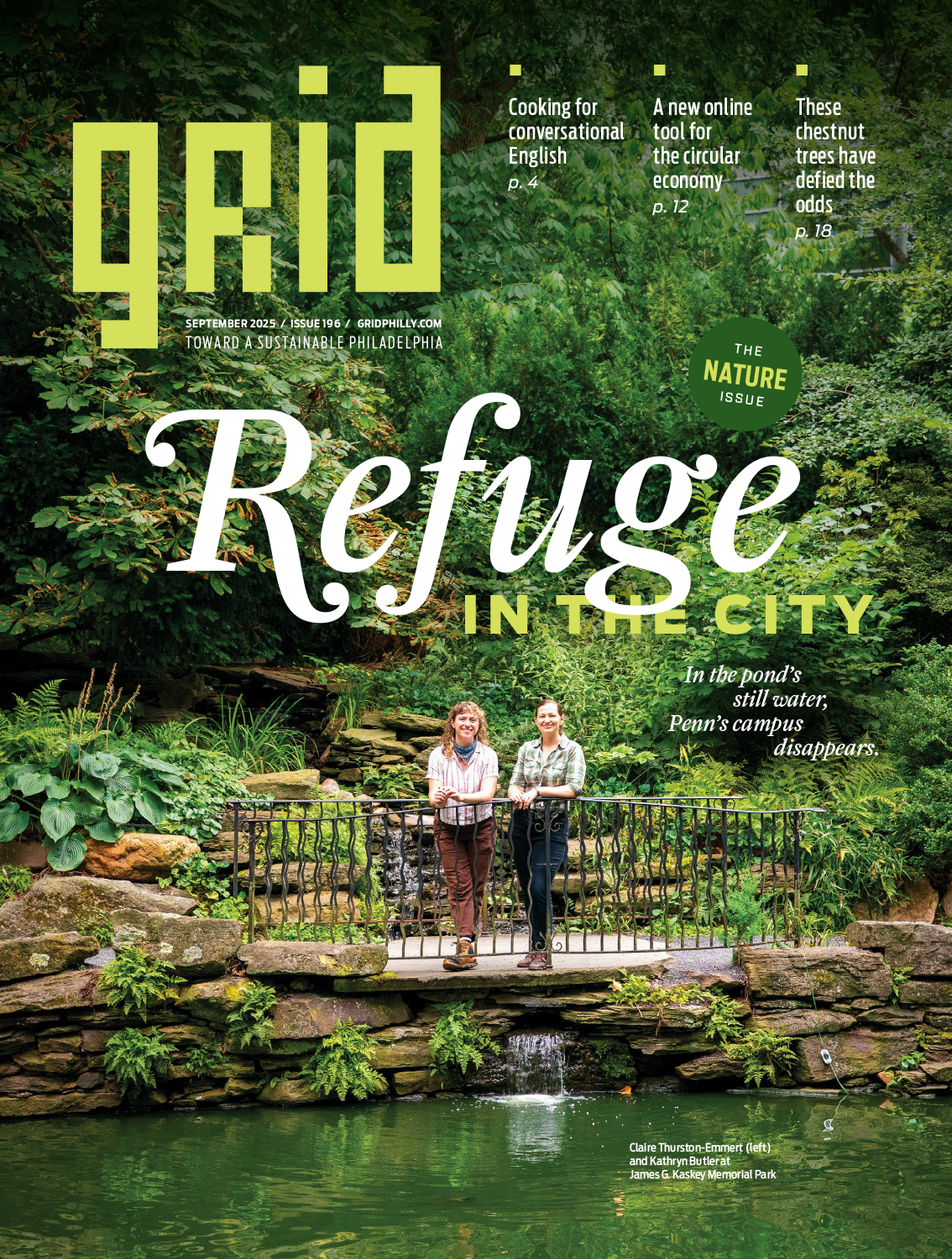

Ill-prepared owners often dump sliders in the nearest accessible body of water, which for much of University City means the BioPond. The turtle owners turn and walk away, but Claire Thurston-Emmert, who manages the BioPond, is then stuck with them. “Just please, don’t drop off the turtles,” she says. The turtles are native to the Mississippi River watershed, not the Delaware’s. And an overpopulation of sliders is bad for them and the pond, no matter where they’re from.

Thurston-Emmert isn’t the only person frustrated at how humans dump red-eared sliders. Out on the West Coast they compete with the local pond turtle species. In Europe and in Asia they bully multiple species of native turtles. Thanks to humans releasing the adaptable critters into the wild, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) includes red-eared sliders on its list of the 100 worst invasive species.

Pet rescue organizations are overcapacity with red-eared sliders for all of these reasons: there are tons of them, and everyone who wants one already has three. Plenty of overwhelmed turtle owners drop them in a nearby waterway and hope for the best.

The same happens too often with cats (also on the IUCN’s invasive species list). Desperate cat owners often end up doing what red-eared slider owners do. They drop the cat at a park and leave.

I met one such cat, named Tommy, when I worked a summer as a seasonal environmental educator for Parks & Recreation. Tommy, a fat, mellow, orange cat, had landed at the Wissahickon Environmental Center (aka the Tree House) more than a decade before, and the staff at the time decided to let him stay. Tommy enjoyed the attention of visitors on the nature center’s big porch or at its picnic tables, except when he had had enough, which he signaled by biting. Like lots of cats, Tommy occasionally enjoyed stalking and killing small animals, which in a park like the Wissahickon meant native wildlife like white-footed mice.

Tommy, I learned, had developed a fan base whose romanticized rural idea of a lazy cat on a porch was at odds with his reality. One time a park visitor actually tried to take Tommy home, but Tommy’s fans objected, and the would-be adopter dropped Tommy back off at the nature center.

This July Tommy met a gruesome end. A larger predator (possibly a coyote or raccoon) mauled him, and Tommy was euthanized. Tommy had actually survived a similar encounter last year, which I would think would have been enough to convince those who cared about him to find him a safer home, but the idea of Tommy was more powerful than the reality of life and death in the woods.

All of this was avoidable. No cat has any business living in a park, whether for its impact on the wildlife or its own safety. If Tommy had been quickly rehomed upon arrival in the Wissahickon, both he and the wild animals he killed would have lived longer lives.

We tend to think of our pets as friendly and innocuous because that’s how we experience them, indoors. Too often we try to will the outdoors into being an extension of our living spaces, pets included, but that doesn’t make it so.