Who you are determines how well and how long you live. In 2012 the life expectancy for white Philadelphians was 78 years, versus 73 for Black Philadelphians, according to the latest Health of the City Report, produced by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. In 2019 that five-year gap remained, and it widened to six years in 2021 as the COVID-19 pandemic dragged down life expectancies. For Black men in 2021 the expectancy was 65 years. The same report found that a Black person giving birth in Philadelphia is twice as likely to suffer major health complications as a white person. Nationally as well as locally, racial disparities in health and lifespan have been stubbornly persistent, as Arline Geronimus writes in her 2023 book “Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society,” even as the public health community has thrown every intervention imaginable at the problem.

“If, like many, you find yourself protesting that these decades-long differences are driven by homicides, AIDS and drug overdose deaths … what if you found out that they were primarily accounted for by death from chronic diseases?” Geronimus writes. Could differences in eating or exercise habits explain the illness disparities? No, Geronimus argues. The difference is not behavior. It is stress that wears people down, “weathering” them, as she puts it. Grid spoke with her to learn more.

I’m used to talking and hearing about stress as an individual problem: “My job stresses me out.” “My kids stress me out.” What’s the difference between this way of thinking of stress and what you write about in “Weathering”? A lot of people have that kind of crazy busy stress. You know, “I had to get my daughter to soccer practice, but I also had to be at a meeting, but I also hadn’t bought any groceries and we weren’t going to have dinner.” But though we feel at that moment that maybe we don’t have options, we really do. We have the resources to say, “Well, I’ll just get takeout for dinner.” Also maybe we can take a vacation or a personal day.

For many members of impoverished, working-class or culturally-oppressed groups, the stressors that contribute to weathering are, first of all, unremitting. You don’t have many — if any — options. It could be that you’re exhausted because you worked three jobs because real wages haven’t gone up for you in 50 years but inflation has. You have to code-switch at work and act respectable, even to people who are awful to you. Maybe you’re waiting in winter weather or summer heat for public transportation that doesn’t come and you’re anxious about how you’re going to be late. You’re worried about your kids. Your mom had a stroke and you’re taking care of her, too. There’s no end. You can’t just take a personal day or even a break.

Or, say you’re a young Black person stopped by the police while you’re driving. Statistically speaking, you’re going to be fine. But, it happens enough that people like you end up dead in an interaction with the police, even if it’s rare, so it makes perfect and reasonable sense that your body goes on alert.

That is not some deficiency. If you grow up in a very stressful world, it’s adaptive to have those street smarts, as we call them a lot of the time. But that alertness and that vigilance also then sets in motion this whole set of physiological processes that, when chronic, weather your body and accelerate your biological aging.

That sounds awful, but how does that translate into people dying younger or having more maternal health problems? While you’re exposed to such stressors, a variety of things automatically happen in your body. This physiological stress response evolved to help our ancestors survive dangerous situations, like tigers coming after them. So you’re overloading your large muscles, including your heart, with oxygenated blood so you can fight or flee.

All your body processes automatically privilege the large muscles. Fats and sugars are mobilized out of storage sites and into your bloodstream so you can continue fueling those large muscles. Proteins in other tissues and organs are broken down to provide continued energy to your large muscles. Immune cells are also mobilized in anticipation of infections. If you’re pregnant carrying a fetus, your body probably is not sending enough nutrients to it while your physiological stress system is aroused because the fetus isn’t going to help you fight or flee — it might even be a drag on your system.

So all your body systems — organs, tissues, down to the cells — are all being chronically stressed. Over time, such persistent stress and high-effort coping with stress erodes your health and makes you more vulnerable to a range of chronic and infectious diseases and conditions, including many that are disabling or life-threatening.

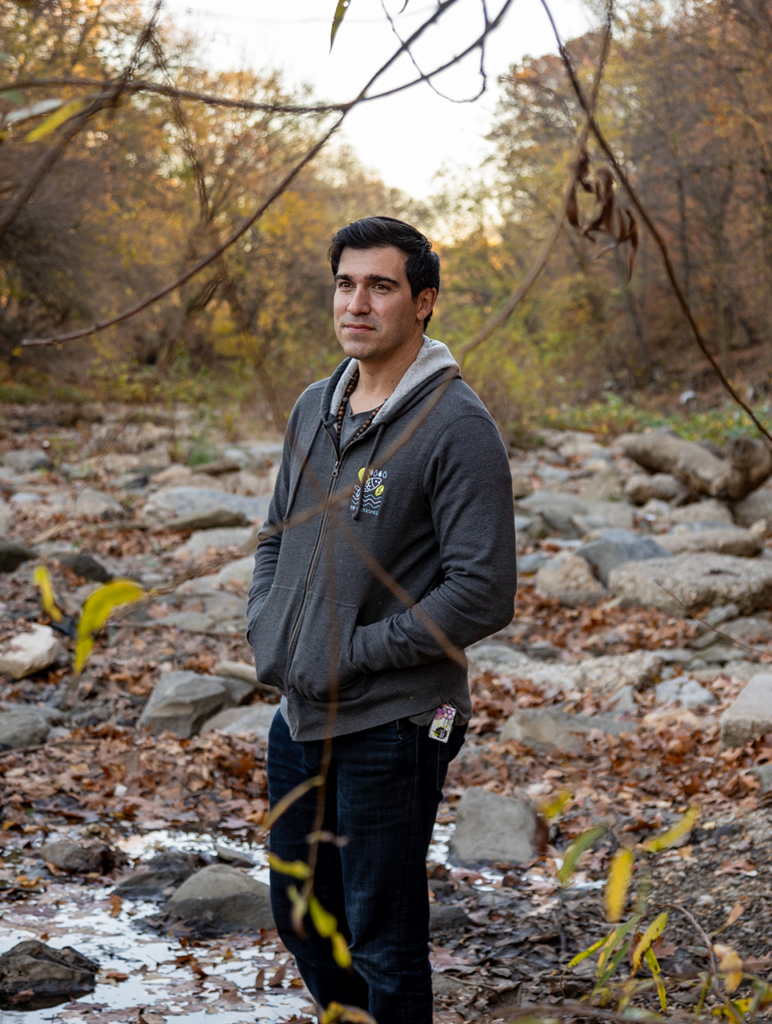

Who is most at risk of weathering and these health effects? Empirically what we have found is Black women are — Black Americans in general but Black women in particular. I could imagine that a lot of this is as true among other groups, like Native Americans, but there’s just not the same degree of study to know that. But it can be individuals in any social group.

What does this recognition about the importance of these external stressors and weathering have to say about initiatives that teach healthy habits, like healthy eating programs? That they haven’t worked. That’s been the main approach of public health and of society more broadly for at least the last 50 years. We’ve presented healthy eating and exercise as the panacea for attaining a long health span. In that time period health disparities have remained large and entrenched. Some have grown, so engaging in healthy behavior is, at best, an incomplete way to address health inequity.

We’ve presented healthy eating and exercise as the panacea for attaining a long health span. In that time period health disparities have remained large and entrenched.”

— Arline Geronimus

It’s possible that these programs help a little, but we think of healthy eating — or even stopping smoking, for that matter — as saving you from something that’s going to get you maybe in your 50s or 60s. So you could have lived to 80, but because you’re going to have heart problems in your 50s and 60s, you’re not going to make it to 80. But what’s happening in populations subject to weathering is they’re having heart attacks or strokes or dying in childbirth due to weathering-related erosion and dysregulation of their key body systems in their 30s and 40s, sometimes even in their teens or 20s.

When you identify the causes of health disparities as big social problems like racism and poverty, it strikes me that the solutions are much more political than just telling people to quit smoking or eat more vegetables. Yes, addressing the fundamental causes of weathering is a societal — not an individual — project. But once you analyze the problem of health inequity through a weathering lens, there are many ways — both small and large — that can disrupt weathering in affected, denigrated populations.

Many of us have been blinded to or even have erased how highly challenging life is for groups who face material hardship, cultural oppression or toxic environmental exposures in their daily round. To the extent we see some of the impacts of life at the margins, we have these false or incomplete narratives: “Well, they just didn’t eat well,” or “They didn’t get a good education, so they don’t understand how important this is,” or “She’s just clearly not a good mother.” We’ve become too satisfied with those superficial and stereotypical, even racist, explanations. But the science is there to inform more effective and just solutions.