Imagine walking on an abandoned pier in Philadelphia and entering a lush park surrounded by a mosaic of wetlands. An elegant heron jabs downward with its long, sharp beak, and you peer into the clear water to see what it’s after. Schools of fish swim over mussels amid waving green plants.

This is the concept my team of ecologists, landscape architects, architects, engineers and land managers organized by the nonprofit Delaware River Waterfront Corporation (DRWC) and led by Olin Studio presented to regulators in 2020: converting stretches of abandoned piers and surrounding waters into resilient refuges for both humans and wildlife that would improve water quality and mitigate flooding. It was a culmination of studies by the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) and a 2011 Master Plan for the Central Delaware involving the input of many.

We were immediately shot down.

Regulators cited uncertainty around the environmental benefits and said that our inclusion of hard structures like breakwaters, which reduce the force of waves, would disturb the existing mudflats. So we took this feedback, collected more data, refined our designs and repeated the process iteratively. Despite our efforts, four years later the project is still not permitted.

Our continued challenges and delays bring to light the barriers to restoring wetlands and shorelines in Philadelphia — and they’ve initiated a long and loud conversation to find solutions.

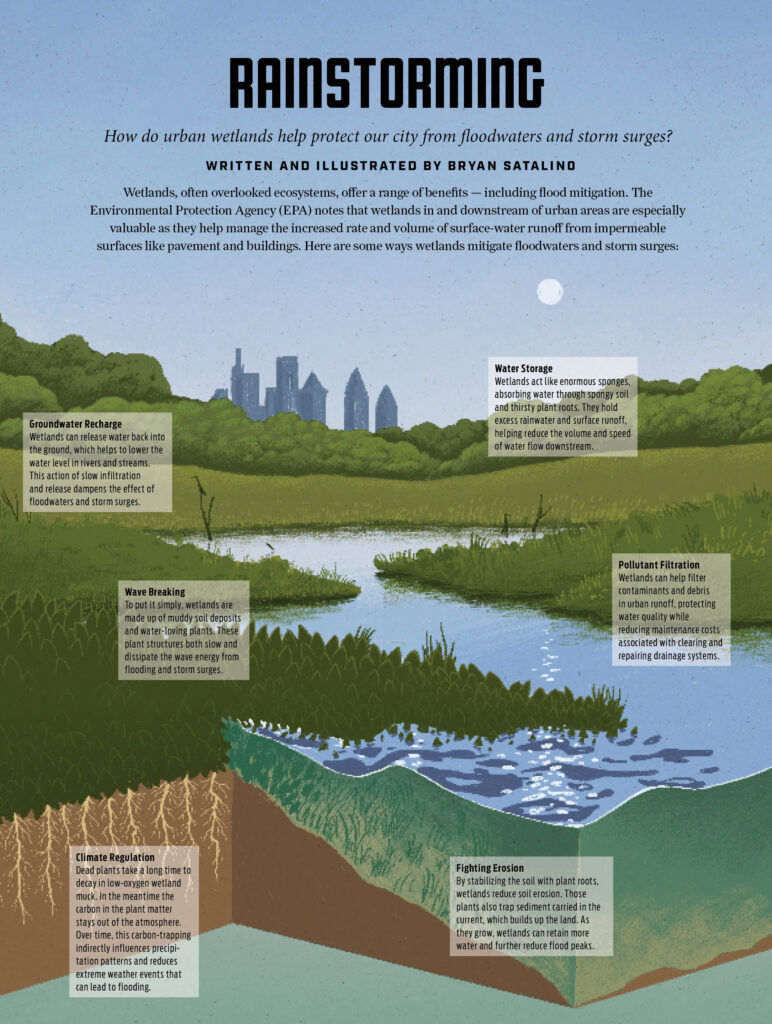

Why should we care about having wetlands in our city? A functional wetland can provide myriad benefits, referred to in ecology as “ecosystem services,” including flood regulation, water filtration, biodiversity support, carbon sequestration and recreation. Philadelphia contains 25 miles of tidal shoreline along the Delaware River and eight along the Schuylkill, plus 118 miles of aboveground creeks. Since the city’s rivers are close enough to the Atlantic Ocean to be influenced by its tides yet far enough away that their waters are fresh, Philadelphia is home to a rare and important habitat type: freshwater tidal wetlands. They provide significantly more diversity than salty or brackish wetlands, which are far more common.

Historic maps indicate that much of Philadelphia, especially South Philadelphia, was covered by tidal wetlands, wet meadows and mudflats. Very little of these remain. Local experts believe that the Delaware Estuary has lost more than 95% of its pre-colonial freshwater tidal marshes, primarily due to human development.

As far back as 1748, Benjamin Franklin argued for draining swamps and marshes to improve public health and agriculture, reflecting the prevailing view that led to massive filling in and destruction of wetlands. This continued until the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972 that gave wetlands federal protection and required anyone looking to work in or around them to go through a permitting process.

It’s one thing to protect the wetlands we still have, but how do we restore or recreate lost wetlands? There is a laundry list of challenges standing in the way.

The biggest challenge is money. Working in a dynamic system — affected by tides that go up and down by six to eight feet twice daily, commercial boats and hardened shorelines often developed right to the edge — requires dynamic approaches, which can be costly. Philadelphia shorelines bustled with industry and transport for over a century, creating a legacy of contamination requiring remediation before restoration can even be considered, which can significantly increase costs.

For example, the shuttered Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery in Southwest Philadelphia sold for $225 million, and several hundred million more dollars are needed to remediate the site. This hefty tab is feasible for a developer envisioning a return on investment after building an e-commerce and life sciences hub, but it is out of reach for the usual ecological restoration funding sources.

In 2024, the William Penn Foundation offered $1 million for climate resilience planning in Philadelphia to be split amongst multiple projects. A national grant distributed nearly $91 million to 55 separate grantees. But this investment doesn’t come close to the potentially $1 billion price tag of the private sector development.

Even with capital campaigns, grants and donation matches, not-for-profit restoration cannot compete with private developers.

The largest tidal wetland restorations in Philadelphia, including Pennypack on the Delaware, John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum and FDR Park, have been enabled by compensatory mitigation — regulations that aim for no-net-loss of wetlands by requiring anyone taking away wetlands to enhance, restore or create an equal value of wetlands (at their own expense) within the same watershed. It can be a valuable tool, but since another wetland must be destroyed to trigger mitigation, it doesn’t increase overall wetland acreage.

Despite the valuable projects already mentioned, more wetlands have been lost than created in Philadelphia. Because mitigation can happen anywhere within the same watershed, cost-conscious developers look for the most available and easiest to restore land, often going as far as Bucks County. This also presents an environmental justice issue where communities experiencing the brunt of development lose the benefits of thriving ecosystems and the offsets are provided miles away to a community often with more natural resources.

Another big challenge is lack of space. In natural areas, rivers and wetlands have room to grow and move and adapt. By contrast, hard, permanent infrastructure leaves them with no place to go. In Philadelphia’s cramped waterfronts, we have small parcels to work with, but restoring a small area of wetlands requires leaping the same regulatory and planning hurdles as larger areas. Even if they cost more per unit, small projects can still be valuable. They’re often our only option.

Culturally, there can be resistance to supporting shoreline and wetland restoration. PWD senior scientist Lance Butler laments that these aquatic and wetland systems have been so disconnected from the upland area for so long that the public as a whole has a poor perception of them. “To change thinking is a tough thing to do,” Butler says. “It is incumbent on PWD and scientists to educate citizens on how important water resources are, not just drinking water or wastewater or stormwater, but all of the ecological properties that Philadelphia watersheds have. ”

Everyone I interviewed mentioned “regulatory hurdles,” the most concrete being the restrictions of the Philadelphia International Airport. The Federal Aviation Administration guidelines recommend that “hazardous wildlife attractants” such as wetlands not be located within five miles of the airport to protect aircraft from potential bird strikes. This restricts a significant amount of historic and potential wetland because of this safety concern.

The greatest challenges to restoring and creating tidal wetlands in Philadelphia are ecological and regulatory.”

— Randy Brown, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection

Other regulations are vague and subject to agency interpretation. Different agencies have different mandates and sometimes their objectives can be at odds, bringing confusion to permit applicants. Randy Brown of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) says: “The greatest challenges to restoring and creating tidal wetlands in Philadelphia are ecological and regulatory.” He explained that regulatory agencies may be hesitant to approve projects where environmental benefits are uncertain. Concerns are even stronger when structures like breakwaters are proposed, as they may require compensatory mitigation.

In other words, wetlands restoration projects could require wetlands mitigation. Practitioners wince at the thought of compensatory mitigation being required for a restoration that makes use of innovative technologies widely accepted elsewhere. While these concerns are valid and aim to protect existing resources, they lack a nuanced and holistic understanding of the requirements for ecological uplift; structures like breakwaters are often necessary to dampen wave energy to allow for wetland regeneration.

“Regulators have a petulance to not think outside of the box, to not address the whole ecosystem services that a complex tidal wetland can provide, especially in urban areas,” Butler says. He adds that most of the areas along Philadelphia shorelines are tidal mudflats. These expanses of muck are valuable, but oftentimes degraded, and a diversity of habitats including tidal wetlands would provide more ecosystem services.

Collaboration is necessary to get past these hurdles. “Based on models in New Jersey and Delaware, the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary developed a framework for a Living Shorelines committee in Philadelphia to include scientists and regulators as well as community groups to forge technical, regulatory and social understanding of waterfront restoration specific to Philadelphia,” says Ellie Rothermel, urban resilience assistant manager for the partnership.

“Science has not matured to the point where we can accurately evaluate these systems and give the regulators and public an accurate representation of ecosystem services,” Butler says. He explains that while these techniques have been successful in other areas, every watershed is unique and more site-specific research needs to be done to better understand the needs in Philadelphia. Unlike a laboratory, the tidal zone of an urban area is full of variables that will only be uncovered by experience.

Learning about the environmental and economic benefits of restoration may also incentivize more funding by giving a dollar value to the ecosystem services and open up permitting pathways, says Butler.

The DEP has launched a pilot program to improve permit processing that will give priority review for environmental restoration projects, according to regional communications manager Stephanie Berardi.

In an era of worsening climate change, we need the resilience that wetlands provide more than ever. “The idea of making habitat in a way that is useful for someone other than a human being is somewhat challenging for people,” says Chris Dougherty, project director for the Riverfront North Partnership. “It shows perhaps how stricken nature has become from our lives in this city. It is a crisis of imagination of what these places can be. A rethinking of these spaces could reshape the story of civic infrastructure to be ecologically and socially resilient.”

Back at the decaying pier on the Delaware, we continue to make small progress by conducting more studies to demonstrate the benefits of the designs, backed by DRWC, whose leadership sees the value in piecing together the necessary funding to do the work right the first time. Our team sees the work as a pilot that can pave the way for similar projects throughout Philadelphia.