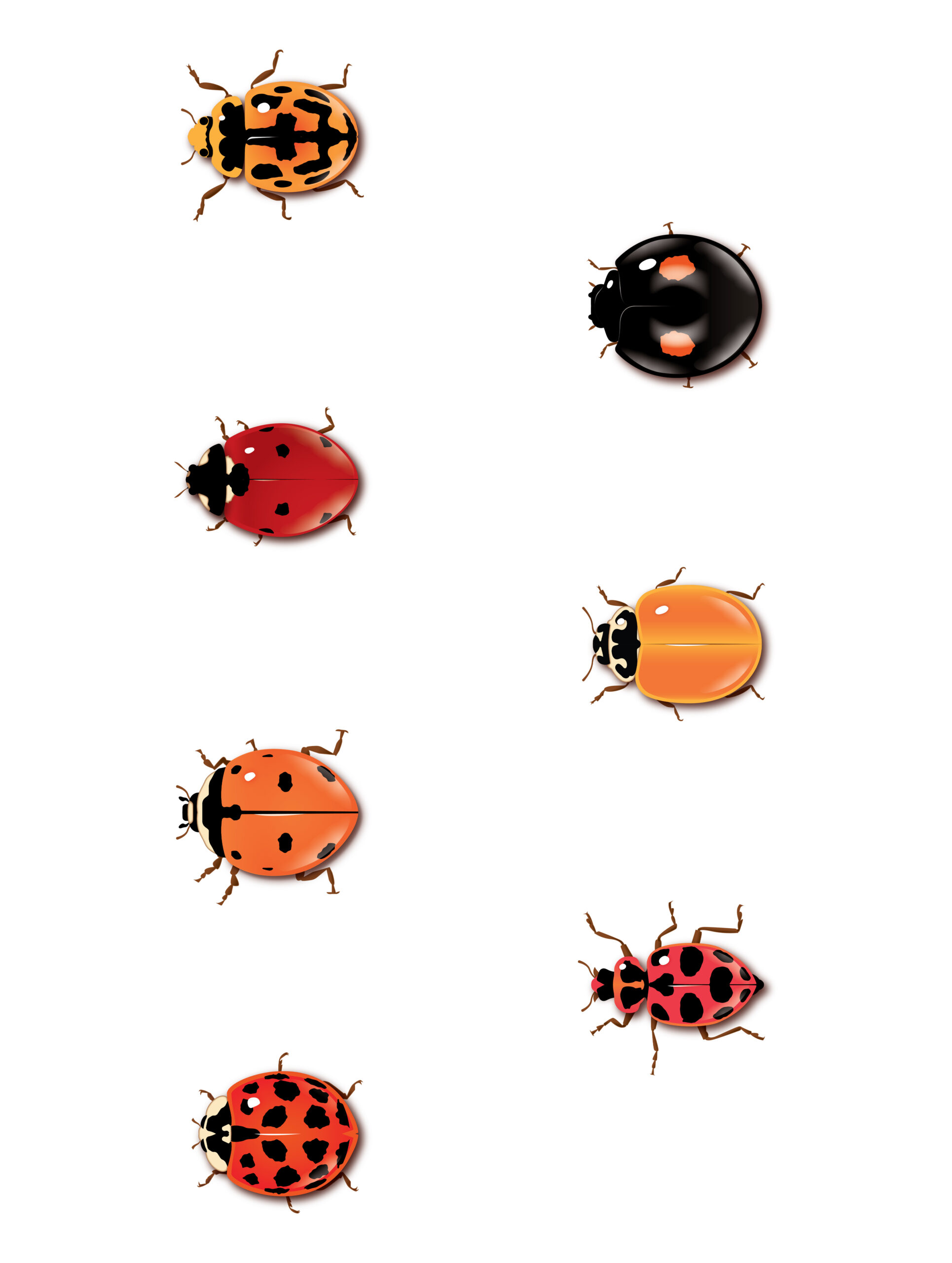

Who doesn’t love lady beetles (aka ladybugs)? They are bright and cheery with that cute, round shape, plus they help gardeners by gobbling up plant-sucking aphids. There appear to be plenty of them; they’re not hard to find outside from spring through fall, and at the end of the growing season, they often make themselves unwelcome inside by squeezing en masse through gaps in walls and windows. Unfortunately, their abundance masks a decline in native lady beetle biodiversity. Most of the lady beetles you’ll see are of a few exotic species, while several once-abundant native species are hard to find.

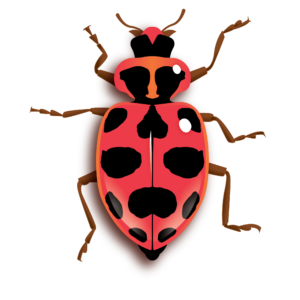

These exotic lady beetles didn’t get here on their own. We released them on purpose as biological control agents meant to control smaller insects without the use of pesticides. Aphid-plagued farmers introduced harlequin lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis) as far back as 1916, and they were reported as established starting in 1988. Today, more than half of the lady beetles reported on iNaturalist in Philadelphia are harlequins, which can appear in a variety of colors and patterns in addition to the classic black-spotted red.

Harlequin lady beetles are like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, according to entomologist and ecologist Mike Raup. In their Dr. Jekyll moments they can work through a patch of aphid-ridden plants and devour all the pests.

“But we’ve also got Mr. Hyde,” Raup says. “It rules the roost in terms of lady beetles.” That native lady beetles such as the nine-spotted lady beetle have declined just as exotics have become more abundant might have been a coincidence (and, as Raup points out, all of this has happened in habitats heavily shaped by humans), but harlequin lady beetles eat the same food and eat the eggs and larvae of the native lady beetle species. “There is good correlative evidence that as Harmonia populations increase, the [populations] of other indigenous and non-native ladybird beetles decline,” he says. “It also eats other beneficial insects such as lacewing and hoverfly larvae.”

Biological control (importing predators and parasites) might still have a role to play in controlling unwanted insects, but today the importation of new species is much harder than it used to be. That’s a good thing according to Kelli Hoover, an entomologist at Penn State who researches solutions to recently-invasive insect pests such as the hemlock woolly adelgid and the spotted lanternfly. It can take more than 10 years of research to make sure that any new bug will afflict only the target species and not become the next harlequin lady beetle. “It’s not easy, but it’s why we don’t have more disasters,” she says.

I am going to check which ones I have been trying to overwinter in the house. Should I be specific about which “to help” through the cold season?

It’s usually the Harmonia overwintering. In general, killing or saving the ones in your house isn’t likely to make a big difference in the overall population either way.