Gun violence does not end on the crime scene.

As many as 200 people can be impacted by a single shooting. It is our responsibility to ask them what they are going through, to listen to what they have to say, and to amplify their voices.

You can also listen to The People Left Behind on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

“I did not get a chance to say goodbye”, Bryana Crump says. “I didn’t know it was the last time”.

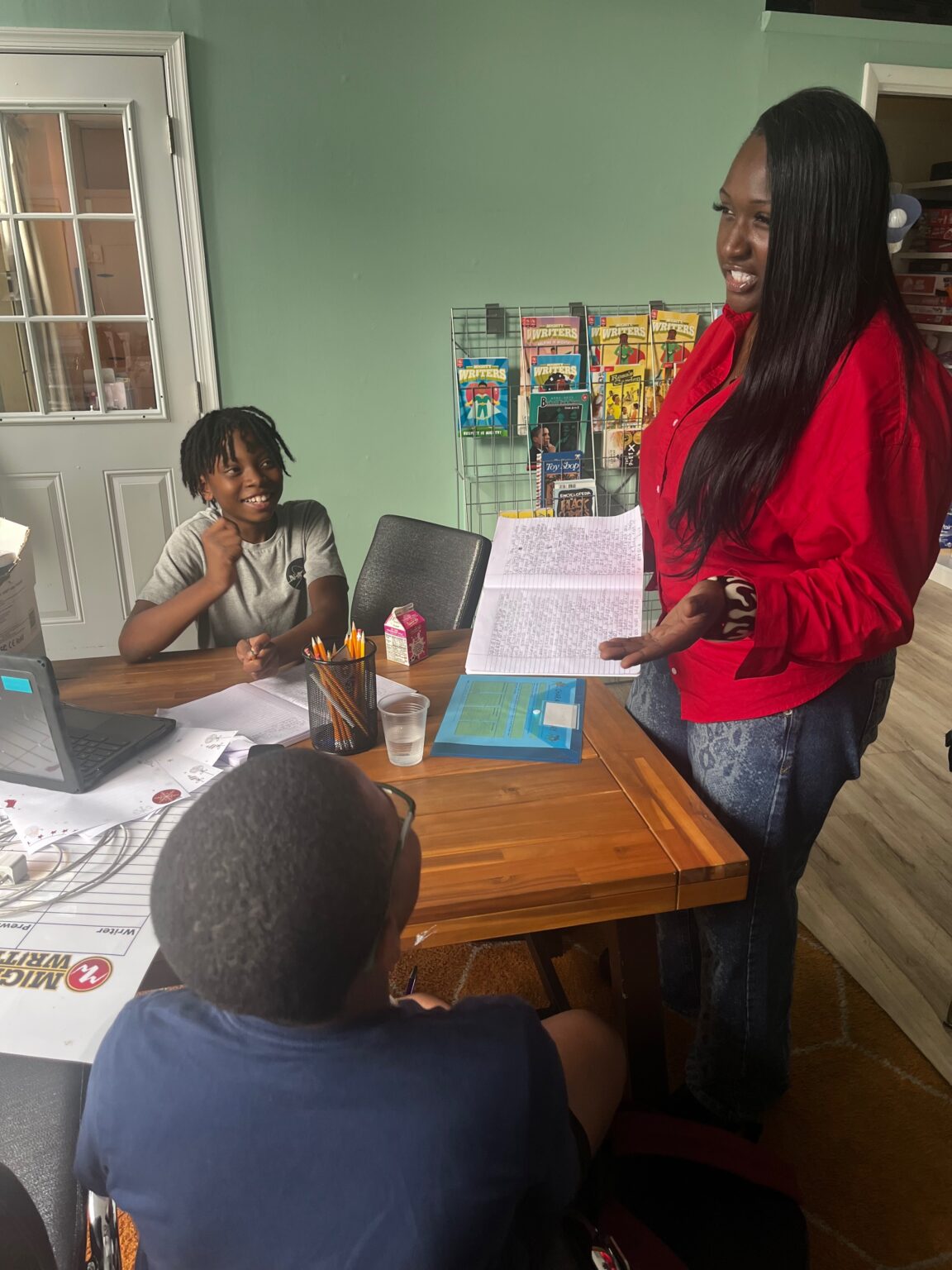

We’re sitting at a school table in the Germantown branch of Mighty Writers, where Bryana runs the afterschool program, helping children with their homework and teaching them reading and writing skills. Because it’s early in the afternoon, there’s no one else in the room.

Bryana tells me about the night of 2012 when her father was shot dead on the doorstep of their North Philly apartment. When it happened, she was eleven and had lived with him, a single parent, for several years. Every night, he would read her a bedtime story and tuck her in.

“Later, alligator”. That’s what they would say to each other before Bryana’s dad switched the light off and closed the bedroom door. “That night”, Bryana says, “he didn’t say anything.” She didn’t speak either. As the memory comes into focus, she thinks her 11-year old self knew that something was off. The silence in the bedroom, in retrospect, was an omen.

Bryana is an adult now. “Adulting” is how she puts it. She’s one of the thousands of Philadelphians who have lost a loved one to gun violence. The sharp decline in the number of shootings and fatal shootings recorded in 2024 brought no silver lining to what they have experienced. Because loss doesn’t come with an expiration date, they are still experiencing it, each on their own terms, while all remain invisible to the rest of us in the city.

“What traditional media miss is the vast number of people indirectly impacted by firearm violence,” says Dr. Vivek Ashok, from the Center for Violence Prevention at CHOP. “A single neighborhood murder can affect as many as 200 people in the community.”

Gun violence reporting in local and national media typically centers on the crime scene; the police investigation; the victims; the charges when the trial begins; the convictions. And then, the news cycle moves on to another shooting. The public rarely gets to learn about co-victims: family members, friends, neighbors, but also first responders. “The first police officer on the scene, the ambulance driver, the trauma surgeon, the nurse – they’re all co-victims in different ways”, Ashok says.

What can we do, as fellow citizens and Philadelphians, for the people who are stuck in the aftermath of a fatal shooting, on the sidelines of yesterday’s news? For those who wake up with grief as their companion, as if every day were the day after, over and over, no matter how many years later? Who sometimes block out their feelings to try and normalize what they are experiencing?

“Through middle school and high school”, Bryana says, “I put that memory in the back of my mind. I was operating as if it didn’t happen.”

Becoming aware of the ripples of gun violence beyond the gun shots and across our community is a first step. We need to raise awareness around us, any way we can, to let other Philadelphians know that some of our neighbors are still coping with the consequences of gun violence in their daily lives, long after the shooting.

Once awareness is established, the real work begins with empathy and kindness. “The love of our neighbor in all its fullness”, French philosopher Simone Weil wrote, “simply means being able to say: What are you going through?”

In communities affected by gun violence, asking the question goes a long way: it recognizes that survivors and co-victims are still experiencing loss and trauma, even though the crime scene has turned into an ordinary place again and everything looks like it’s back to normal. Pain does not go away with the flowers, the posters, the police tape.

Asking someone how they are doing is also an invitation for that person to tell their story and share it with the world. The ability and will to listen, in a way, gives them a voice back – and an opportunity to regain agency over how the story is told. They are no longer names and pictures in the paper, people you feel sorry for, wishing you will never come to know their pain. They are putting their story in their own words, and, so doing, breaking the stigma of victimhood. Because every story is different, when they are telling theirs, the people who lost a loved one to gun violence exist as complex human beings, not one-dimensional victims.

Does that mean telling one’s story can help with the healing process, or serve as therapy? That is for grief counselors, therapists, social workers to say. First and foremost, that’s up to the people left behind. For those who lived through what Bryana Crump had to live through, the ability to bring meaning to the trauma might be less about moving on, and more about the comforting knowledge that they are not alone: there are other people out there listening or ready to listen.

“My experience is a part of who I am”, Bryana says. “But that doesn’t mean that I have to constantly relive it. I’ve learned how to live every day with this feeling, not letting it take over my life.”

Yes: to fight gun violence, we need to apply political pressure in Harrisburg and in D.C. We need law enforcement agencies to do a better job at finding ghost guns. We need to support neighborhood associations better and more. We need to have support systems for kids and young people when school is out. And we need news outlets to report shootings when they occur.

There are multiple factors to this fight. If we are to stand a chance, our strategy also needs to involve survivors and co-victims of shootings. It starts with us, as neighbors. It starts by saying: we care. At the end of the day, it’s about remembering we are a community.

We are here to listen, if you want to talk about what you are going through.

Julien Suaudeau