On Feb. 11, 2025, U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz released a database of 3,483 National Science Foundation grants that the Senate Commerce Committee, headed by Cruz, described in a press release as “woke DEI grants.” Cruz had previously used the list of grants to prepare an October 2024 report claiming that the Biden administration had politicized science.

Buried in the list was a 2022 grant for $449,633 to Drexel University to develop a pilot program to crowdsource stormwater inlet cleaning in flood-prone neighborhoods in Camden, New Jersey. The pilot project survived both its mention in Cruz’s database and the funding chaos of the first year of the Trump administration, but the episode sheds some light on what is at risk as the political winds shift against environmental justice programs, and how these efforts can survive.

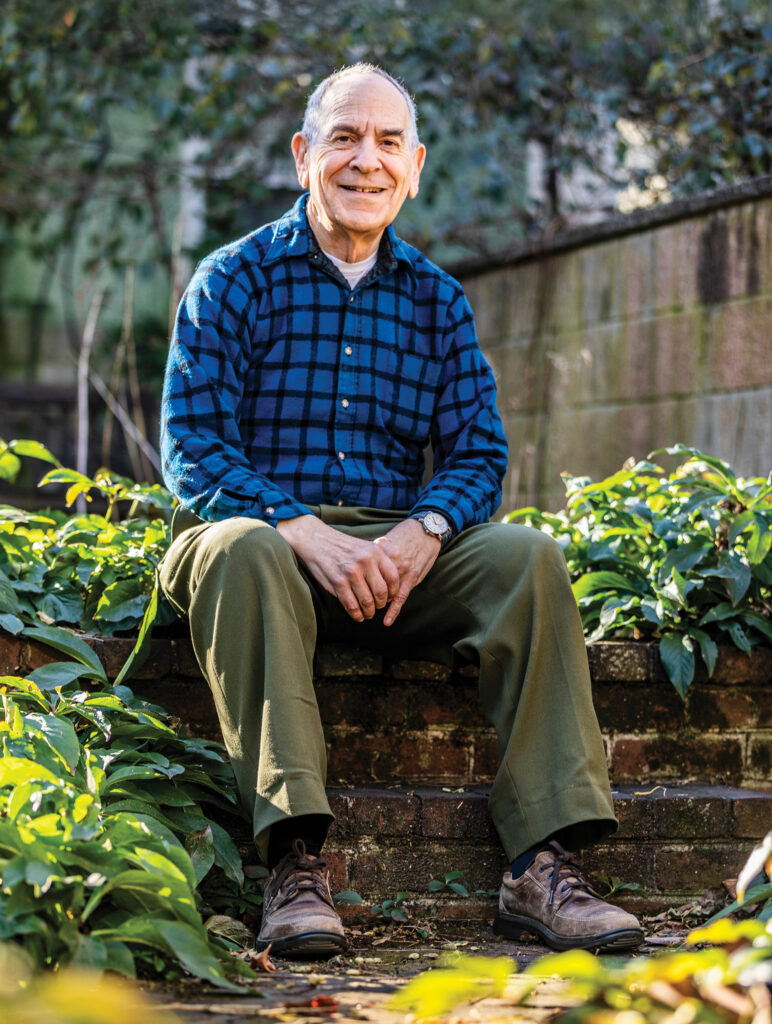

“We wrote this grant many years ago,” Drexel Engineering professor Franco Montalto says.“What it has turned into is the development of an app that enables crowd sourced inlet cleaning to reduce flooding.”

Many cities have crews that regularly clean trash out of the inlets, but cash-strapped Camden often falls behind.

As anyone who has had to circumnavigate a giant puddle at a street corner knows, a clogged stormwater inlet can lead to flooding. Water that should be draining into the stormwater system can spread up the street, creating barriers to transportation and flooding property. Many cities have crews that regularly clean trash out of the inlets, but cash-strapped Camden often falls behind, says Montalto.

Christina Allen, who lives in the Waterfront South neighborhood in Camden, says streets flood routinely when it rains for a prolonged period of time. “It doesn’t have to be really heavy,” she says. When the neighborhood’s main street, Ferry Avenue, floods, “You have to travel around the whole area to get home.”

So when she heard about the app, called Cleanlet, at a community meeting a couple years ago, she gave it a shot. She wasn’t working at the time, and the app offered a little extra money as well as a meaningful task to devote herself to. “It was something to look forward to,” she says.

Allen was one of 25 Camden residents who signed up to use Cleanlet. Montalto’s team gave them rakes, shovels, gloves and other basic tools and supplies. The users volunteered to adopt nearby stormwater inlets, and the app notified them when rain was on the way so they could clean out trash ahead of time. A photo before and after would prove they had cleaned the inlet, earning them points that could culminate in a financial reward.

At Cruz’s direction, staff from the Commerce Committee had searched a public database of National Science Foundation grants for “DEI keywords and phrases,” such as “under-represented” and “minority,” which Montalto’s team had used to describe Camden’s Cramer Hill neighborhood in the grant description.

Despite landing in Cruz’s database, the pilot ran to its originally planned conclusion. It did run into practical hurdles, such as dry weather that reduced user interest. “Last summer we had a drought,” Montalto says. “We launched the pilot and then it was like ‘who cares, it’s not raining.’” Montalto’s team had also planned to monitor flooding at inlets to measure the impact of cleanings, but volunteers ended up choosing inlets convenient for them to clean, not necessarily where the researchers could place sensors.

Such hiccups are to be expected in a pilot, and Montalto plans to use what they learned through the Cleanlet experience to develop next-generation resiliency crowdsourcing apps.

Montalto says the changing political climate won’t scare him off from researching resiliency. He has already found funding from the William Penn Foundation to continue working in Camden. “I’m going to work where I think the research has the greatest impact. I think people should continue to do that.”

Back in Waterfront South, Allen is still cleaning out her local stormwater inlets. “What opened my eyes was the app,” she says. “It’s still in my head that when it rains, it’s time to clean out the inlets.”