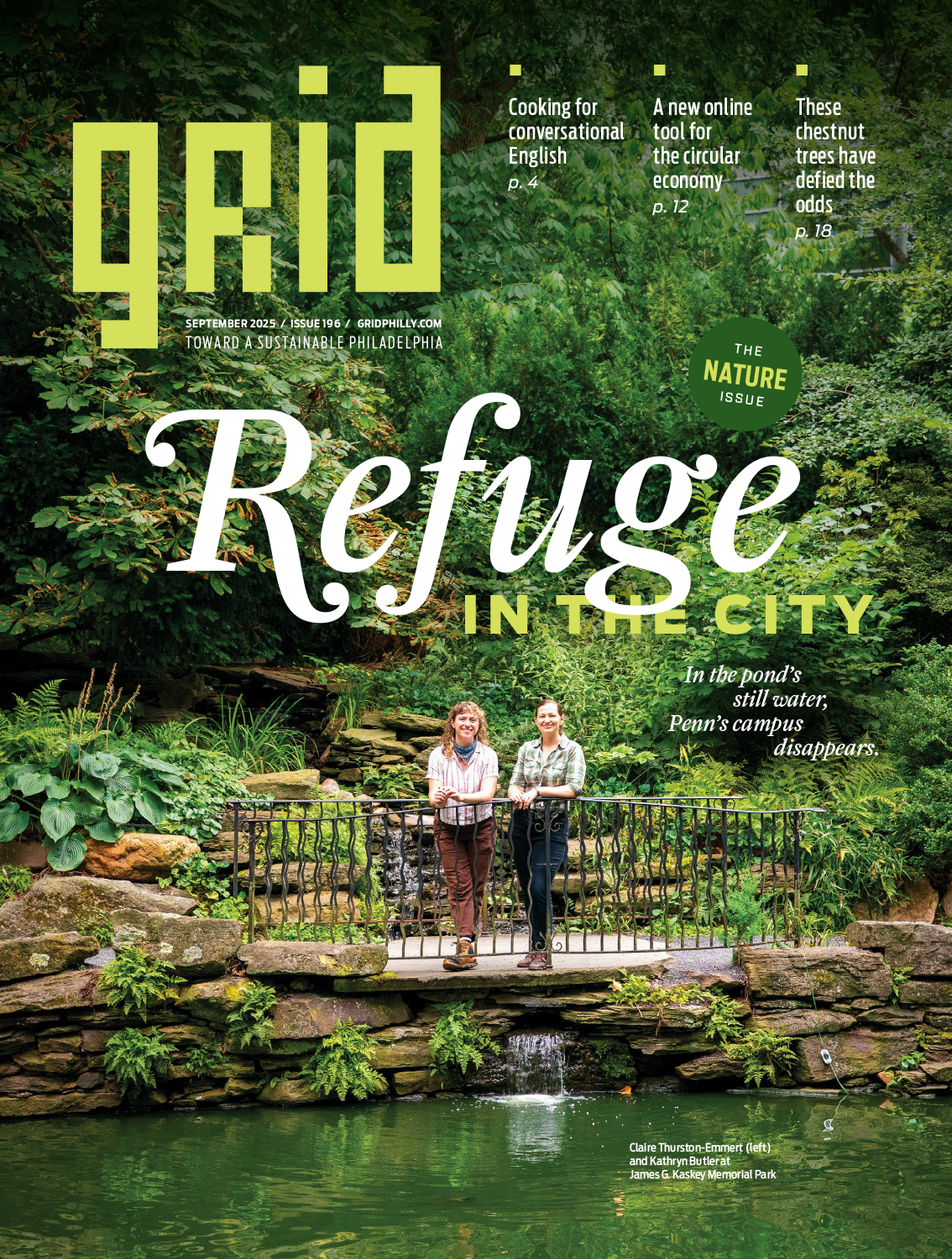

I parked my bike at nine in the morning on a heat-dome summer day and walked down the path into the University of Pennsylvania’s James G. Kaskey Memorial Park (better known as the BioPond). Under the tree canopy I immediately felt cooler after my sweaty bike ride. I paused to admire a stately American elm tree, dominating the landscape with its columnar trunk and spreading branches forming a massive umbrella, or, on that sunny day, a parasol. Most elms were wiped out by Dutch elm disease in the 20th century. Arborists have been treating this one to stave off the disease, a reminder that Penn’s entire campus is an arboretum, with trees grown as much for their heritage as for their shade.

Business-casual-clad workers paused at the pond on the other side of the elm tree, presumably enjoying the peace of water and greenery on their way to the offices where they’d spend the day staring at computer screens.

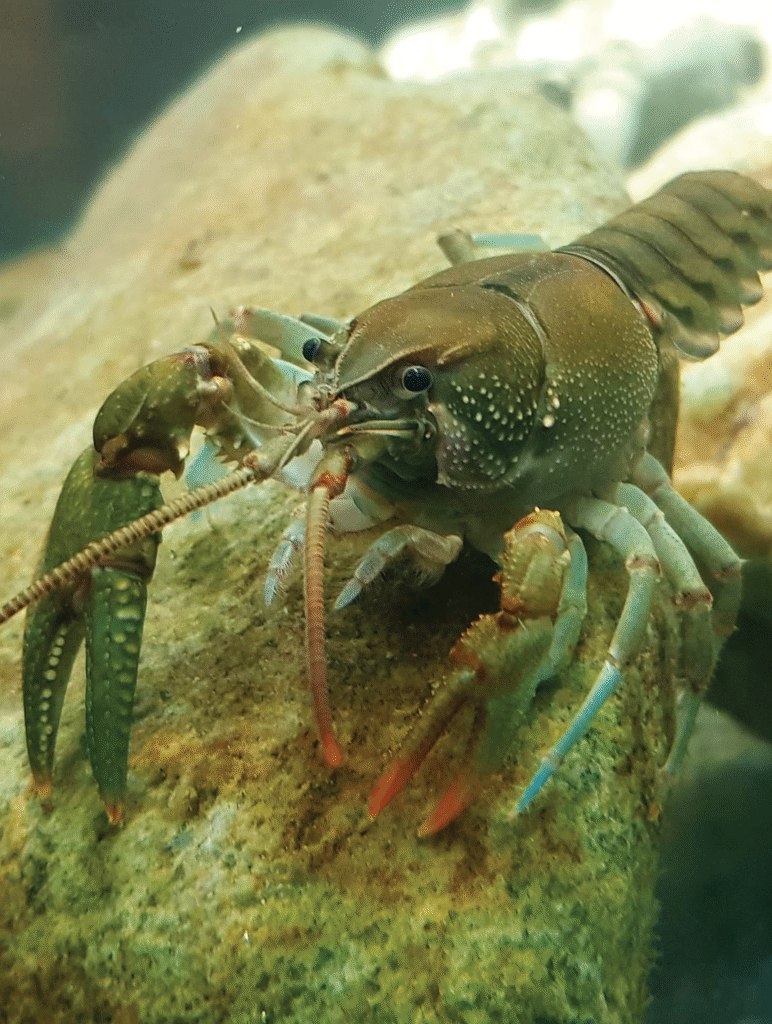

I strolled a lap around the pond and noticed a turtle — a red-eared slider — on the gravel path, probably a female looking for a place to dig a nest. Bullfrogs sang their deep, resonant “jug-o-rum” calls from the edge of the water below. A female mallard duck swam by with six ducklings in tow. A catbird warbled from within a nearby shrub.

Garden supervisor Claire Thurston-Emmert showed up to give me a tour, pruning shears in a leather holster on her belt. Thurston-Emmert says that the gardeners’ strategy is to promote native biodiversity, whether that’s with wildflower plantings or with trees like sweetgums intended to grow into the canopy as older trees in the garden reach the ends of their lives.

“A lot of people say, ‘When I was at my most stressed out, I would come and study here, or cry here.”

— Claire Thurston-Emmert, garden supervisor

Some of the wildlife, such as the birds, arrive at the park on their own. Some stay and nest, like the mallard. Others are just taking a break mid-migration. Observations on eBird dating back to 1900 record 123 species. If I had visited in early May I might have seen blackpoll warblers on their way to the boreal forests of Canada.

Other wildlife can thank humans for their home at the park. The non-native red-eared sliders are commonly (and illegally) sold as silver-dollar-sized hatchlings. Owners unable to care for them as they grow to the size of dinner plates regularly dump them in the pond, which is bad for the pond and the turtles.

Kathryn Butler, greenhouse and garden manager, joined our walk, and we talked about the history of the park. At the end of the 1800s, botany professor John MacFarlane convinced the biology department to establish a research garden. Originally five acres, the garden had two ponds and long rows of beds. Eight greenhouses allowed students to study plants through the winter.

Over time new buildings whittled the five acres down to three, and only one pond remains. In 2000, according to the park’s website, Richard and Jeanne Kaskey donated funds to renovate the pond and then endowed funds for the ongoing maintenance of the garden.

In the park, almost every plant has either been intentionally planted or permitted to grow, but in other ways the gardeners take a hands-off approach. “Except for plants of significant value and at particular risk, like our elm, we don’t really do pest management,” says Butler. “We find that most things start to just take care of themselves. We have a lot of aphids right now. That’s bird food. And other-insect food.”

Today the BioPond remains an oasis amid the traffic and never-ending building boom of University City, a place to take a break, watch birds and listen to frogs. Thurston-Emmert reports, “A lot of people say, ‘When I was at my most stressed out, I would come and study here, or cry here.’”