There is nothing easy about running a small business, especially when that business revolves around food. In most restaurants, there’s the mountain of to-dos that must be accomplished before the doors even open; the never-ending puzzle of scheduling employees; the toothy-smiled rigor of providing seamless hospitality; and actually serving up good food. For producers and suppliers, the challenges are related but different: staying on top of regulations, licensing, taxes and invoicing, plus all of the logistics of growing/catching/foraging/processing products and finding avenues to sell them.

These challenges exist even before factoring in sustainability: building community, treating employees and customers with dignity, reducing waste, lowering your carbon footprint — and maybe even turning a small profit. To pull this off is an extraordinary endeavor.

What inspires an entrepreneur to assume this mantle, and what keeps them in the fight, not just year after year, but across decades?

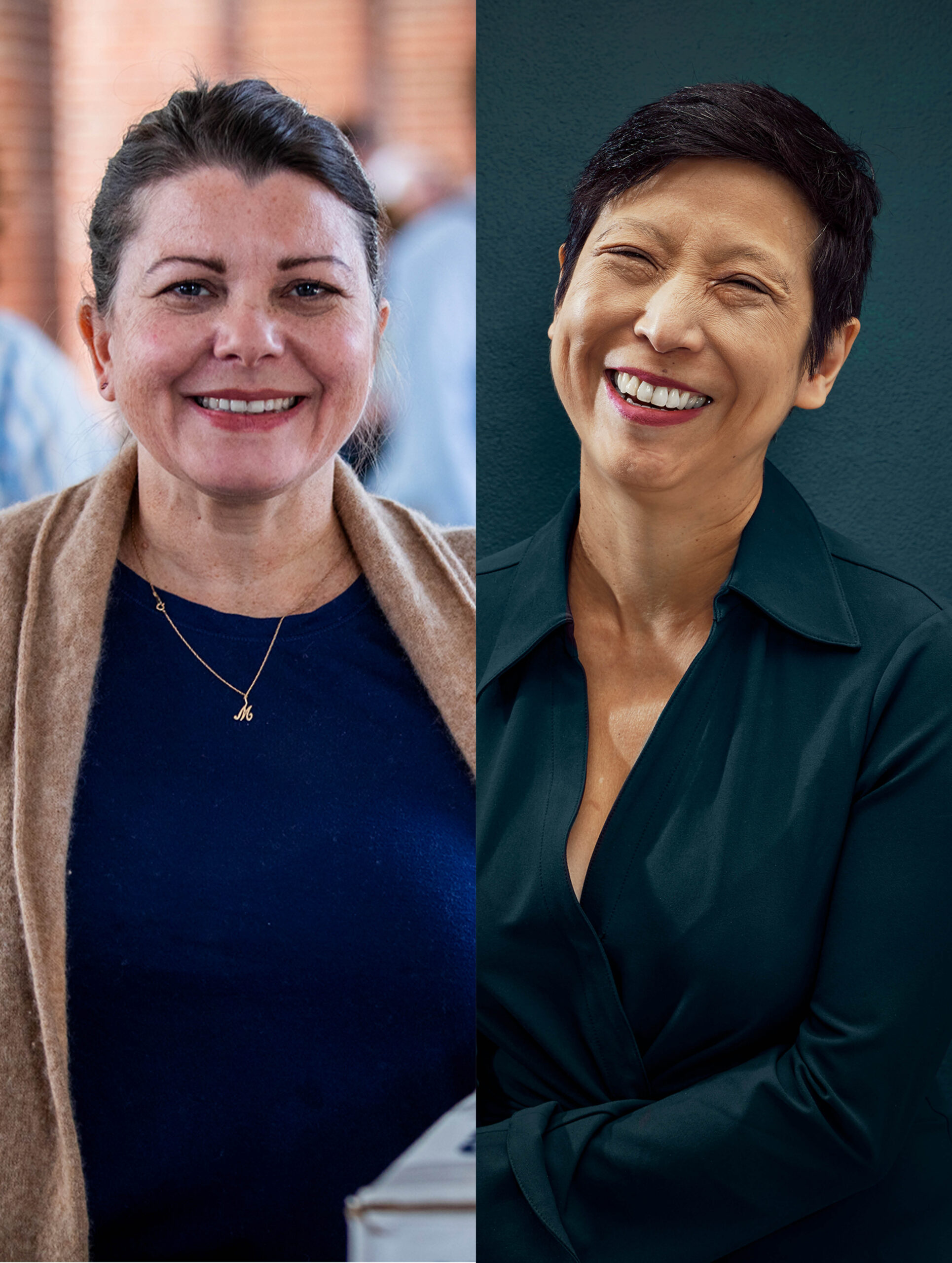

We sat down with two leaders in the local sustainable food community to find out: Amanda Bossard, owner of Otolith Sustainable Seafood, and Ellen Yin, founder and co-owner of High Street Hospitality Group. These visionaries have been at the forefront of sustainable food systems for a generation. Both started out before “sustainability” was a mainstream buzzword and they’ve adapted and innovated their respective ways into the mid-2020s.

Amanda Bossard,

Otolith Sustainable Seafood

In 1992, Amanda Bossard left Fishtown, where she’d lived all her life, to study marine biology at Alaska Pacific University in Anchorage. After graduating and working for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, she switched gears in 1999 and entered the world of commercial seafood. She worked aboard a 65-foot schooner for a commercial fisherman named Murat Aritan (also a native Philadelphian who soon became her husband). Bossard then founded a wholesale seafood distribution company with a focus on sustainability. She named it Otolith, a nerdy reference to a salmon’s ear bone.

Otolith’s wild seafood, including salmon, halibut and shrimp, is caught and processed in Alaska, where the couple still lives for part of the year. It’s then shipped to Philadelphia where it’s stored and distributed to wholesale accounts and retail customers throughout Pennsylvania (find it at Riverwards Produce), New Jersey, Delaware and New York City.

What were the beginning days of Otolith like? Murat would catch the fish and I’d make phone calls, letting people know what we were catching, when it would be landing and what the opportunities were to have it custom-processed and sent to them. It was leaning off the side of the boat trying to get a cell phone signal in the middle of the ocean — that’s what it was in the beginning.

Was doing this kind of business in a sustainable way always important to you? Yes, and I look at sustainability from a science-based perspective and also from the fact that the quality really does matter. In order for wild-caught seafood to be sustainable, it has to be part of something people are interested in learning about. My commitment has been to make this idea more mainstream, not some niche-y thing on the periphery. I want Otolith to be a catalyst for redefining industry standards.

What does it look like to run a seafood distribution company in a sustainable way? All of our specialty seafood is harvested in a protected marine area that is only accessible to low-impact harvesters, and that excludes trawling, which is one of the most problematic fishing practices in the world. [Ed. note: Trawling is an industrial method of fishing where a fishing net is pulled through the water behind one or multiple boats.]

When considering a new processing plant, what I always do first is buy and inspect their product. I want to know how it gets handled and what the quality is like. I’m always looking for the best, most consistent nutrition and flavor. I use these pillars as my guide when I’m buying custom services from small processors, and I see if I can request special things like shorter processing times and various cut and portion sizes to reduce packaging. It’s all about the relationships; these are people in small towns with small populations and a lot of producers and processors in Alaska know me.

What are some of your greatest challenges? There are so many obstacles to compensate for. Mainly, though, the margins aren’t great, the competition is enormous and more companies are getting stock market exchange funding to go corporate.

Have you noticed your customers’ attitudes toward sustainable seafood change over the years? There are a lot more ways to get information about sustainable seafood now and I’m thrilled about that. When I first started Otolith, my retail consumers were older people, but I have a lot of younger customers now so it seems the message is reaching them. Economically, I think people find it a little harder [to afford] than they used to. I remember when it was a huge deal to me where seafood was in my finances. One of the reasons I stayed on the boat even though it was hard was that I wanted access to wild-caught seafood to be able to eat it and feed it to my kids.

Ellen Yin,

High Street Hospitality Group

Ellen Yin has been a champion of sustainable, local dining in Philly for nearly as long as the concept has been familiar to Philadelphians. Her first restaurant, Fork, which she co-founded with Roberto Sella in 1997, has earned a stellar reputation not only for its inventive New American cuisine but also for setting a lofty standard for flawless hospitality.

Yin is a multiple-time James Beard Foundation Award nominee and winner in 2023 for “Outstanding Restaurateur;” under the umbrella of High Street Hospitality Group, she’s opened multiple restaurants, including High Street and a.kitchen; and she’s helped propel the careers of a varsity squad of hospitality pros including chefs Terence Feury, Andrew Wood and Eli Kulp (now the culinary director of the group).

When did you first encounter the concept of sustainable food sourcing? I was tired of eating at restaurants where the menu never changed, so it started with seasonality. Fork’s first chef, Anne-Marie Lasher, and I worked at the White Dog Café — I was a bartender — and we’d both been indoctrinated into Judy Wicks’ philosophy about community and working with farmers and artisans. In the ’90s you couldn’t get everything farm-to-table, there wasn’t even that term yet. For me, it was about creating a local ecosystem and supporting the local economy.

How did you communicate the philosophy of farm-to-table to your customers? It’s not that we had to convince people, but we did host lots of farm dinners to engage our guests with what we were doing. And that’s just being passionate about it, not trying to “educate,” just sharing our beliefs and making it as fun as possible.

Has the availability of locally-grown products changed since 1997? In the beginning, it was mostly herbs, tomatoes, basic produce, but that has changed ten-fold now. You can buy grains, meat, dairy products and cheeses … so many different products. Our food ecosystem has evolved so much over the past 25 years.

What are some of the challenges of sourcing this way? The biggest roadblocks initially were that small farmers didn’t have mass distributions systems or accounting systems and sold things by the bushel, which makes it hard to cost things out. Like “10 sprigs of thyme” on a handwritten invoice — what does that even mean? But farmers have gotten more sophisticated and places like Lancaster Farm Fresh Cooperative, Green Meadow Farm and Plowshare Farms distribute for smaller farms and sell everything by the pound, which makes things more efficient on our end.

What are some of the joys? It’s all about personal connections, creating an ecosystem. It’s knowing that people share your values. When you hit it off with a new vendor, it’s very invigorating and fun. For creative types, it’s exciting to frequently have a new palette for inspiration, especially in a business that’s so fast paced.

You’ve taken a holistic view of sustainability that goes beyond food. Can you explain what that means to you? Creating a sustainable business model really has to do with labor. In this industry, there’s often no health insurance, no schedule — especially in the kitchen — no discussion about hourly rates or mental health. The culture of leadership and management hasn’t been inclusive, though that is shifting. People are trying to experiment with new restaurant business models, and there are a number of bills the Independent Restaurant Coalition, which I’m a member of, has put forward. So many people want to make these changes, but it’s really hard. I connect with people across the country because I want to hear what’s working and not working.