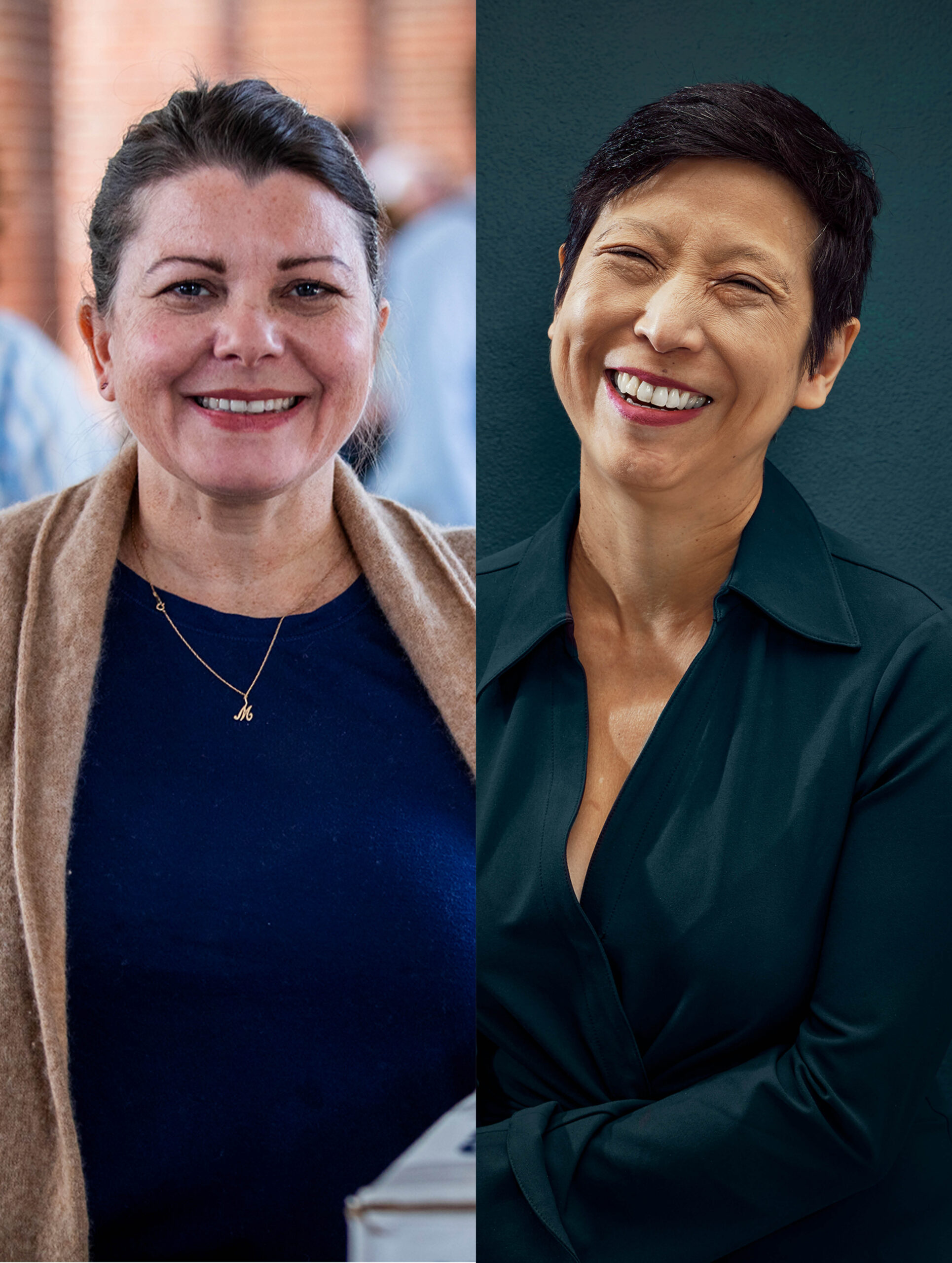

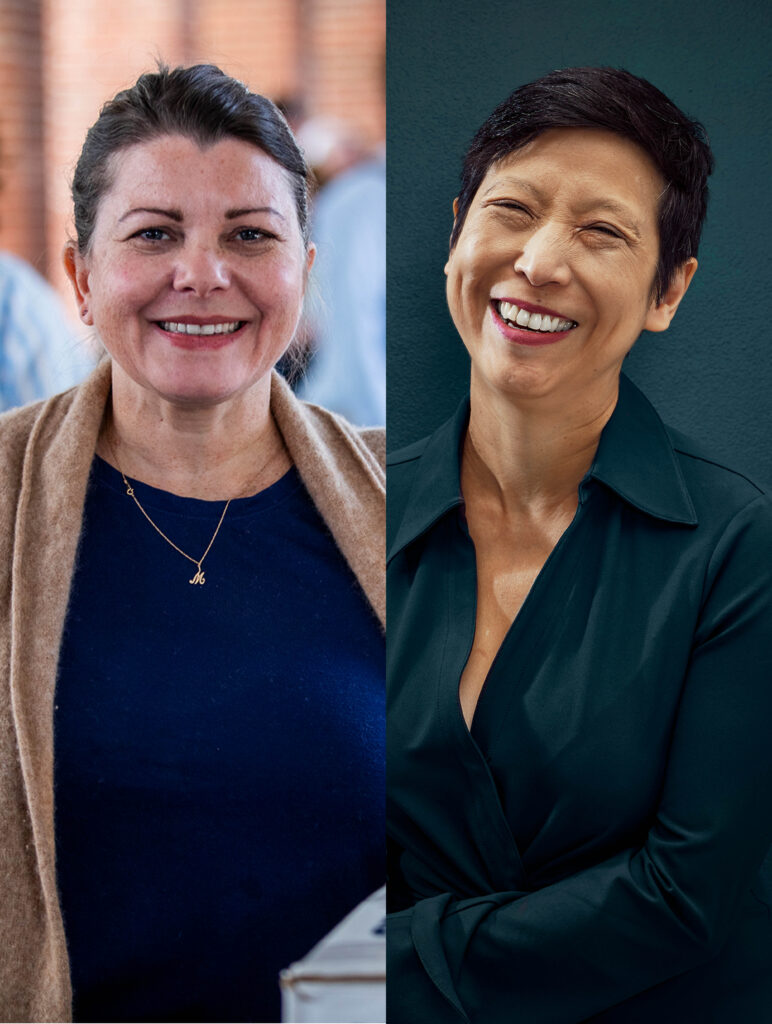

On a warm Saturday morning in September, Mégane Simões and Sara Dufner — the volunteer managers of the Northern Liberties Community Compost Program — are tucked behind a playground at Liberty Lands, hard at work. Saturday is drop-off day, a time when neighbors bring buckets and bags of food scraps, which, over weeks and months, Simões, Dufner and an intermittent crew of about half a dozen fellow volunteers turn into compost. “It’s the easiest way to compost for somebody who hasn’t composted before,” says Simões. “It’s free. You don’t have to do anything besides drop off your food scraps once a week.”

While Dufner aerates food scraps in one of the the three compost bins, Simões empties some of the finished compost into a sifter. Today, they’ll process about 200 pounds of food scraps from about 20 drop-offs. “We’re having a little trouble keeping up with the demand. People are really into it. We have people who come in from Fishtown and Fairmount,” says Dufner. “We actually had to stop advertising our program because it’s been too successful. We ran out of space in the bins.”

The Northern Liberties Community Compost Program is one of 13 compost sites Philadelphia Parks & Recreation supported in 2019 as part of a city-wide Community Compost Network. Modeled off a similar program in Washington, D.C., the program provided each of the sites with a three-bin compost system, tools and training for volunteers. (Due to the pandemic, composting at most of the sites didn’t kick off in earnest until 2022.)

It’s free. You don’t have to do anything besides drop off your food scraps once a week.”

— Mégane Simões, Northern Liberties Community Compost Program

The program emerged from an executive order Mayor Jim Kenney signed in 2016, which committed Philadelphia to a goal of diverting 90% or more of the city’s waste — including food waste, which at 17%, accounts for the largest share — away from landfills by 2035. In 2019, the City estimated that 214,000 tons of food waste are generated in Philadelphia each year. Of that, 206 million pounds — about half — are sent to a landfill or incinerator.

Composting has a number of benefits. It saves cities money on landfill fees (one estimate puts the savings at up to $250,000 annually for every 10,000 homes composting), recycles nutrients into local soil and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. But back in 2019, the City’s only compost program for food scraps was in the Department of Prisons, and there was no City-supported program for residential food waste, which accounts for at least 40% of all food waste. Today, according to the City, turning food scraps into compost is not the only way to divert organic waste from landfills, but it’s perhaps the most promising.

“When we talk about zero waste goals and waste reduction goals, it’s one of the biggest areas where we can get bang for our buck,” says Casey Kuklick, deputy director of the City’s Office of Clean and Green Initiatives. “Composting is one solution of several that we can use to deal with organics, but it’s the one that I would say has the most infrastructure around it right now.”

In the eight years since Mayor Kenney signed his executive order, composting has indeed become more common across Philadelphia. In 2020, the City provided the privately-owned Bennett Compost with City park land to use as its headquarters; in exchange Bennett picks up food waste at the City’s recreation centers and provides the City with finished compost. In March, the City announced that at least 10 new community compost sites will join the network this year and begin composting in 2025. The footprint of private composting services, meanwhile, has also expanded.

However, the vast majority of Philadelphia’s more than 650,000 households still don’t have access to composting, underscoring the lengths still yet to go for Philadelphia to become a zero-waste city. Now, with 2035 just a decade away, advocates, composting entrepreneurs and City officials are figuring out how to move the needle.

Brenda Platt is the director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Composting for Community project, which advances local composting. Methods for managing food waste, she says, exist within a hierarchy of preferability. The best option is preventing waste in the first place by buying only what you need and eating it. Then there’s donating unwanted food to hungry people, and routing food not suitable for human consumption to animals. After that, there’s home composting, then community composting, then larger and larger municipal or commercial compost operations. Disposing of food in landfills, she says, is the worst option and should be banned.

“Cities spend millions and millions of dollars on trash, and those costs are only going to increase as landfills fill up,” Platt says. “To hedge against future increases in cost, cities should be looking at ways to reduce trash and support businesses and community-driven operations so we can build that economic power and keep the social benefits that come with community composting.”

In cities across the country, Platt has helped cities do just that. In 2018, for instance, she supported a bill in D.C. City Council that created an incentive program for residents to buy home composting systems after completing a training program. And here in Philadelphia, Platt worked with the City to get its Community Compost Network up and running in 2019.

Today, initiatives like the Northern Liberties Community Compost Program are a testament to the network’s benefits. But it faces a number of challenges. Since its formation, the number of sites in the network has shrunk, and the number of Philadelphians who can access it remains relatively small. Three of the original sites have since left the program. Greensgrow Farms dropped out when the organization shut down in 2022. Hardy Williams Academy stopped participating after the two teachers who were running the program left the school. And Pearl Street Garden dropped out due to a staffing shortage. Today, of the 10 sites that are now formally part of the network, at least one is non-operational and just one — Liberty Lands — is processing food scraps from the general public on-site; the rest are only open to students or members of community gardens. Washington, D.C., a city with half the population as Philadelphia, has five times as many community composting sites.

According to Andrew Kirkpatrick, the urban greening coordinator for Farm Philly, the urban agriculture program of Parks & Recreation, the City wants to continue expanding the network. But the program — which Kirkpatrick estimates costs between $40,000 and $80,000 dollars — depends on grant funding, which isn’t guaranteed.

Nic Esposito, who served as the City’s Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet director from 2017 until its dissolution in 2020, studied D.C.’s community compost network back when he worked at Parks & Recreation. Recently, the urban farm he co-manages, Emerald Street Community Farm, became one of the newest members of Philadelphia’s network. He believes community composting could be a “part of a major waste reduction strategy for neighborhoods,” along with backyard composting and curbside pickup services. But the City, he says, isn’t investing enough in diversified composting services.

“In the same week, you might take some stuff to the community composting site, use your InSinkErator, maybe even put some scraps out curbside because you had too much,” he says. “You should have those options. And the City should be able to supply them for you.”

A diversity of options for would-be composters is important, Esposito says, because Philadelphians have different barriers to participation, which can include time, money and space. Some Philadelphians, like Simões and Dufner, will happily spend hours every week processing food scraps at their local park, or in their own backyard — but many can’t or won’t. Some Philadelphians will happily pay a private composting service to pick up their food scraps, but many can’t or won’t.

Tim Bennett, the founder of Bennett Compost, understands this well. (Full disclosure: Alex Mulcahy, Grid’s publisher, is a business partner in Bennett Compost.) In 2009, he started his business with 10 customers. Today, he has 6,000 residential customers who pay a monthly fee for a weekly pickup of their food scraps, and around 120 commercial customers. The growth, he says, has been exciting, but he knows there’s likely a limit to it. “There is some additional appetite for people who are willing to pay,” he says. “But there’s even more appetite for people who are either willing to pay less than what the private compost companies are charging, or would do it if it didn’t cost them money.”

Recently, Bennett has been testing that theory through a series of grant-funded pilot programs in partnership with the nonprofit New Kensington Community Development Corporation. In the spring, Bennett began offering no-cost or low-cost composting services, including drop-off programs and curbside pickup, in Kensington, an area of the city where the company has relatively few customers. “We’re trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t,” says Bennett.

Dave Bloovman, who co-founded Circle Compost in 2016, is also experimenting with lower-cost composting services. This year, his company launched a pay-what-you-wish community drop-off site at Trinity Memorial Church. And the company is applying for grants to provide composting services for people who can’t afford it through its nonprofit, Circle Change Co. “Funding composting programs like ours in underserved communities would be a great way to make it accessible,” says Bloovman.

That’s just going to have to be a choice that the City will have to make. If they want to ever be able to offer no-cost or subsidized services, they’re going to have to foot some of that bill.”

— Tim Bennett, Bennett Compost

Grants are useful for funding these small experiments, Bennett says, which can demonstrate how lowering the price of composting for residents can boost participation. But ultimately, he’d like to see the City partner with private composting businesses to provide no-cost residential composting at scale. “That’s just going to have to be a choice that the City will have to make. If they want to ever be able to offer no-cost or subsidized services, they’re going to have to foot some of that bill,” he says. “Some of that money maybe can come from the savings that the private companies provide when they take that material out of the city’s current trash stream.”

The City isn’t considering that kind of partnership — at least not yet. But Kuklick of the Office of Clean and Green Initiatives says there are a number of options on the table to reduce food waste and expand composting. He says the office is considering starting educational campaigns to reduce waste from the source and pulling ideas from other cities.

“We’re looking to New York and some of the innovative things they’ve done with Bigbelly composting trash receptacles,” he says. “We’re also considering how we can remove organic waste and food waste in particular at the backend of the waste stream and put it to more productive use potentially through digestion or biogas,” he says.

For now, these are just ideas. A plan to expand the capacity of the Fairmount Park Organic Recycling Center is one potential solution in the works. The center, which has been in operation for more than 40 years, currently only accepts yard waste such as leaves and trees. But if a grant application the City has filed is approved, Kuklick says the center could begin to also accept food waste from City agencies.

It’s a promising large-scale solution, but it’s not guaranteed. In the meantime, volunteers like Simões and Dufner are keeping composting free and accessible to as many neighbors as they can, a labor of love that points to composting’s potential even at the smallest scale. “I don’t think of it as a task,” says Simões. “It’s fun.”

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit

This content is a part of Every Voice, Every Vote, a collaborative project managed by The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Lead support for Every Voice, Every Vote in 2024 and 2025 is provided by the William Penn Foundation with additional funding from The Lenfest Institute for Journalism, Comcast NBC Universal, The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Henry L. Kimelman Family Foundation, Judy and Peter Leone, Arctos Foundation, Wyncote Foundation, 25th Century Foundation, and Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation. To learn more about the project and view a full list of supporters, visit