At the Pulaski Zeralda Community Garden in Germantown, the air is thick with the scent of green onions and okra. These vegetables grow from some of the 38 plots, including one dedicated to a local women’s center. This season alone, the garden yielded blackberries, strawberries, tomatoes, okra, peppers, corn and collards. The garden participates in the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) City Harvest program and donates produce to community fridges and a local church.

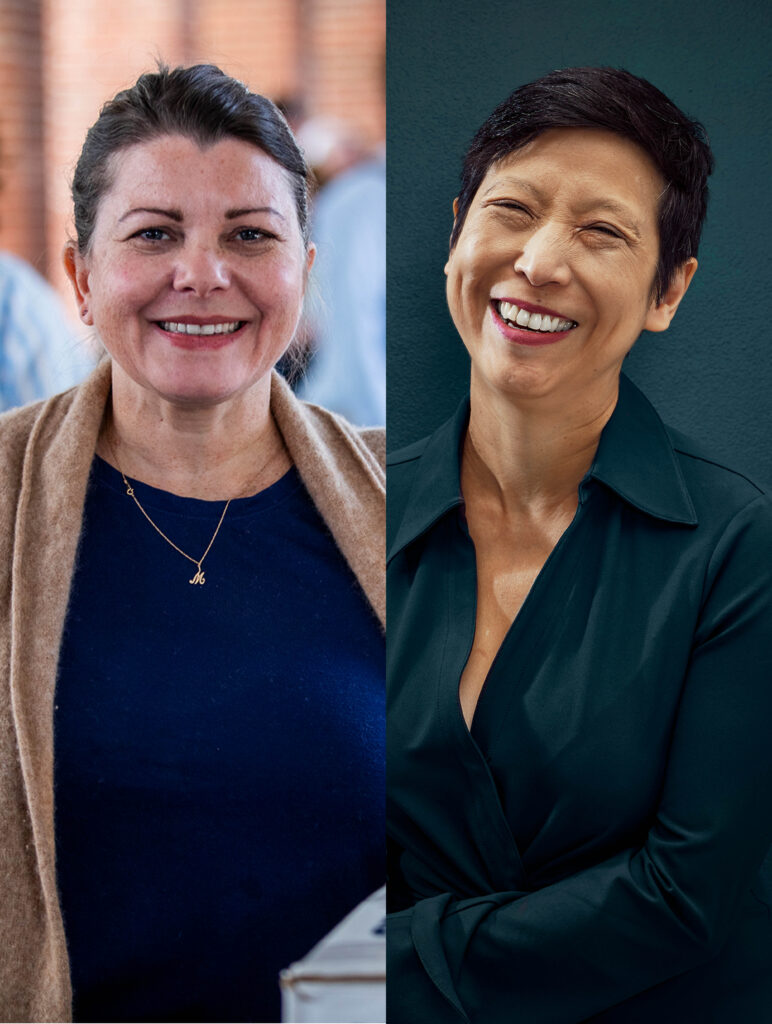

“This garden is good for the soul. It keeps me grounded,” says Tracy Savage, talking with her garden co-coordinator Dee Dee Risher about their connection to the space. “For me, this garden is a tie to the rural land I grew up [on] in South Carolina,” Risher says.

Pulaski Zeralda is one of many community gardens across Philadelphia that serves as vital greenspace in a neighborhood grappling with vacant, blighted lots. They provide fresh food, social connections and a sanctuary from urban life. Yet, land security is a constant battle as developers seek to buy up and build on these cultivated plots. Recent legal changes, including a Philadelphia City Council bill facilitating garden land transfers, offer hope amid gardeners’ continued struggles to protect their communities’ green havens.

In neighborhoods across Philadelphia, some 40,000 lots lay vacant. Nearly 75% of those abandoned properties are privately owned, according to the City of Philadelphia. Many are strewn with trash, overgrown with weeds and may be tax delinquent.

These vacant lots are especially common in Philly’s low-resource neighborhoods. Besides being eyesores, they can have serious social impacts on residents. “Dilapidated, vacant lots increase residents’ risk of depression and stress, which may contribute to socioeconomic disparities in mental illness,” said Eugenia C. South, MD, an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and lead author of a 2018 study about the effect of greenspaces on mental health. “Our data shows that greening vacant lots can have a positive impact on the health of those living in these neighborhoods.”

This garden is good for the soul. It keeps me grounded.”

— Tracy Savage, Pulaski Zeralda Community Garden

In response, neglected lots from Cheltenham to Cobbs Creek have been transformed into community gardens and greenspaces. “Philadelphia currently has between 300 and 400 community gardens,” says Adam Hill, director of Community Gardens at PHS.

In 2014, the Pulaski Zeralda gardeners began the process of purchasing the two parcels of city-owned land on which they’d been gardening for years. And while, technically, they had been gardening as squatters for a quarter century, Councilmember Cindy Bass supported their efforts to preserve the garden. With the help of the Neighborhood Gardens Trust (NGT), led by executive director Jenny Greenberg, and the Public Interest Law Center’s Garden Justice Legal Initiative, the gardeners were successful in making the purchase two years later.

While community gardens like Pulaski Zeralda provide vital resources, land security remains a challenge.

In 2023, NGT purchased two lots directly from developers, preventing the destruction of gardens that had thrived there for decades. But NGT can’t save them all: Over 140 community gardens have been lost to development since 2008, according to the Philadelphia Garden Data Collaborative, including La Finquita, a celebrated garden in Kensington that closed in May 2018.

Recent shifts in state and local policy could make it simpler for community groups to secure ownership of the land they’ve lovingly cultivated for years. In September 2024, a new Pennsylvania law reduced the required time for adverse possession — a legal tool that allows individuals or community groups to claim ownership of property they’ve maintained. Previously, gardeners had to continuously use a lot for 21 years before applying for ownership; now they can do so after just 10 years.

“This could be a really helpful tool for the hundreds of Philadelphians who have been maintaining side yards for a long time,” Greenberg says. “If a lot is privately owned and you can’t find the owner, there’s potential to gain ownership through this law.” However, the process is still complex, requiring continuous and exclusive use for a decade, possession must be hostile — the owner can’t have granted permission — and use of the land must be “notorious,” or obvious. “Things like signs, fences and raised beds can help,” adds Hill.

Sari Bernstein, staff attorney with the Garden Justice Legal Initiative, which provides pro bono legal counsel to community gardens, believes the new law will make a significant difference. “I believe many more gardens will qualify for permanent preservation under this law,” she says. “The garden community in Philadelphia is very organized and these people are doing a service to their neighborhoods.”

Another legislative change came this past spring via Philadelphia City Council Bill No. 240187, which allows the Philadelphia Land Bank to bypass sheriff’s sales when it buys foreclosed properties. It can then transfer ownership to community gardeners, who will maintain them as life-giving resources in neighborhoods. Councilmember Kendra Brooks, co-sponsor of the bill, wrote in her newsletter to constituents: “In dozens of high-poverty neighborhoods across Philadelphia, community members have stepped up to clean up vacant lots and transform them into gardens. I support garden land belonging to the communities that care for them.”

Greenberg says funding the Land Bank would enable them to acquire more tax-delinquent properties for community gardens and transfer them to NGT for permanent preservation. “The Land Bank is acquiring lots from the U.S. Bank lien situation, which is very important, but there are so many other gardens that could be preserved as well.”

These legal changes offer hope for Philadelphia’s community gardeners, many of whom have spent years fighting for their greenspaces. But it remains to be seen how effective these bureaucratic measures will be in bringing real, tangible change. NGT is working towards protecting 70 total gardens by next year. “You can’t put a price on things like greenspace and flood reduction in our city that is dealing increasingly with climate change,” says Greenberg, who is also on the board of the Land Bank.

In 2023, the gardeners at Pulaski Zeralda faced a new challenge. The vacant lot next to them that had been privately owned and tax delinquent had been purchased by a developer for $11,000. The developer, Nickle Holdings, LLC, had cleared the debt and was preparing to build a four-story apartment building that would block out much of the sun at the garden. The community strongly supported the garden and only had a week to mobilize before the local zoning hearing that would recommend a decision to Councilmember Bass on the eight-unit apartment building.

“We worked with a local attorney to navigate Germantown politics,” Greenberg says. “And the community really turned this crisis into an opportunity.” With mounting public pressure in favor of the garden and financial support from NGT, garden advocates including Risher and Savage won the legal battle and eventually purchased the lot for $65,000. The developer still walked away with a tidy profit. The Pulaski Zeralda story is one of success, but not every community garden is so lucky.

Back at the garden, the hum of rush-hour traffic fades into the background as members envision what’s next. “It’s exciting to think about this land becoming something great,” Savage says, looking at the empty lot that will soon take shape with plans for beautification, with more raised beds and a community space for meeting and children’s programming.

Savage’s mother, Glenda McCall, who’s been part of the garden for over 32 years, beams with pride. “I used to bring Tracy and her sister here as kids, and now, look at her, helping the next generation,” she says. “When I get to the garden, I take my shoes off, put my feet in the dirt and read my Bible. It’s so peaceful here.”