Say you’re renovating your kitchen. You weigh the pros and cons of granite versus butcher block countertops, you compare different brands of convection stoves and you work through stacks of tile samples for the backsplash. You’re thinking mostly about style and function, and perhaps the sustainability of the materials, but how about slavery?

Surely you would rather not buy anything produced with forced labor, but how would you know if you were? Materials supply chains stretch around the globe and the workers are often far away, in countries that you (and your contractors) are unlikely to visit.

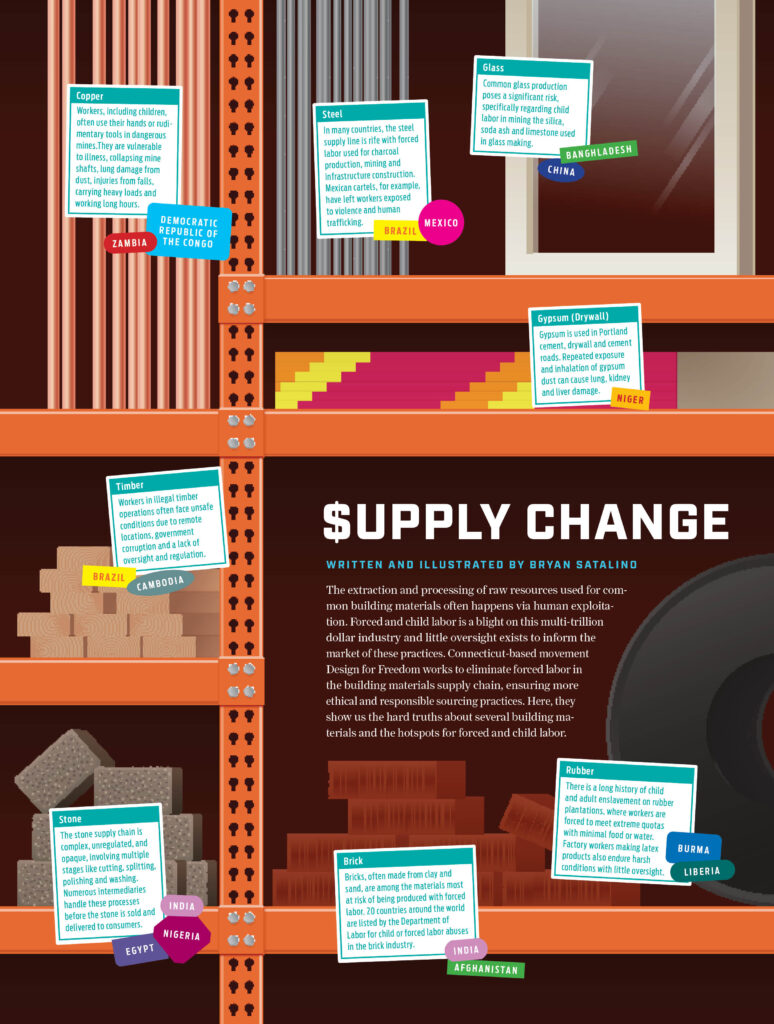

The Connecticut-based advocacy group Design for Freedom has elevated the problem, pointing to the 28 million people held in servitude around the world and drawing the connection between the work they are forced to perform and the materials used in our buildings.

Take natural rubber (latex). Latex comes from trees grown in tropical rainforests. Workers slash the bark to channel the white, sticky sap into buckets. Labor conditions in South America during the rubber boom of the late 1800s to early 1900s were notoriously brutal, with thousands of indigenous workers enslaved to tend the trees in plantations. Today, labor problems continue to plague the industry. In plantations in Burma (Myanmar), for example, companies connected to the military force children to work.

Unfortunately for consumers attempting to shop conscientiously, supply chains constantly shift and twist, with manufacturers switching suppliers depending on price and availability. If one rubber supplier runs out of stock, a flooring factory in China might work down their list and, out of the need to meet their orders to wholesalers, pick a supplier who can deliver on time — whether or not they’ve been properly certified.

The U.S. Department of State tracks information about child and forced labor overseas, but some products simply haven’t been investigated. It reminds Kristen Suzda of Philadelphia’s Re:Vision Architecture of trying to find out about the recycled content in materials in the early days of LEED, a green building standard introduced by the U.S. Green Building Council in 1998. Back then, manufacturers would say they didn’t know. Now, she says tracking recycled content has become easy with certifications and credentials displayed on companies’ websites, but that is not the case with forced labor.

If we never ask, manufacturers will never know this is important to us and adjust accordingly. No one wants to be the one who has to answer ‘yes’ if someone asks ‘were enslaved people involved in making this product?’”

— Kristen Suzda, Re:Vision Architecture

“When I call manufacturers and ask about slavery in supply chains I get silence on the other side of the phone,” she says. “They aren’t prepared to answer. It doesn’t mean they’re not interested or don’t care, but this is a new area.”

The Living Building Challenge (a more stringent standard than LEED) mandates the exclusion of forced labor where possible, but requires applicants for their certification to advocate where it isn’t. They write in their program manual that, for industries that lack third-party certification, the applicants must send advocacy letters to the corresponding trade associations encouraging them to develop independently-verified standards.

So what can you do? Mindful Materials offers a growing list of vetted options to choose from. You can also speak up — ask your architects, contractors and suppliers about forced labor. “If we never ask, manufacturers will never know this is important to us and adjust accordingly,” Suzda says. “No one wants to be the one who has to answer ‘yes’ if someone asks ‘were enslaved people involved in making this product?’”